by Judy Gonyeau, managing editor

mirror/paperweight selling at RubyLane.com

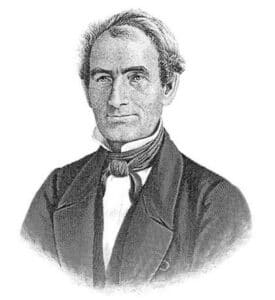

When it comes to the name “Remington,” think “mechanical.” The engineering ability of founder Eliphalet Remington showed its prowess when, at the age of 23, he forged his first rifle barrel, convinced it would be something that would be an improvement to current examples or, as the other story goes, to give him what he could not otherwise afford. Either way, it was the start of a name that is noted for its ingenuity, whether applied to gun barrels and accessories, adding machines, sewing machines, one of the earliest computers, or typewriters.

Ingenuity

Remington went on to build his business by moving their foundry and forge to a logistically pleasing spot on 100 acres along the Mohawk River near the town referred to as Morgan’s Landing (now Ilion) in New York. With the opening of the Erie Canal, moving inventory was easier than ever, and this spot was just right for moving the rifle barrels out to clients.

Remington became E. Remington & Sons as his children Philo, Samuel, and Eliphalet III joined their father and helped to add to the product lines. “Remington” appeared not just on rifle barrels but also percussion locks (made in England), brass gun “furniture,” or features including patch boxes and butt plates. Longarm and revolver production took over the company’s focus in the 1840s.

In 1856, the Remingtons added the manufacturing of garden and agricultural implements to their list of products. During the Civil War, Remington supplied the army with small arms. Following founder Eliphalet’s death in 1861, Philo took over the firm’s management and made the ingenious decision to add the manufacturing and creation of sewing machines and typewriters, both shown at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876, to the company’s product line.

The Start of a Revolution

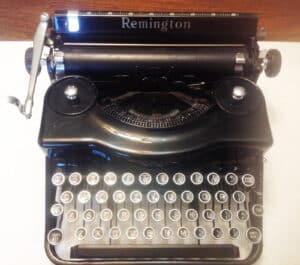

Even with the success of the Remington Arms Company, another engineering marvel became the star of the Remington name: the typewriter.

The Sholes and Glidden typewriter was the first commercially successful typewriter, designed by American inventor Christopher Latham Sholes, Samuel W. Soule, and amateur mechanic Carlos S. Glidden in 1866.

In 1868, Remington took on a contract with the Sholes and Glidden typewriter company to manufacture their typewriters. With that successful endeavor, they moved on to produce typewriters bearing the Remington name based on the Sholes and Glidden typewriter with a few design and mechanical adjustments.

One thing that drove this inventive typewriter ahead of other “writing machines” being created by other manufacturers was the arrangement of the letters on the keyboard, known as the QWERTY layout. The first Remington typewriter used this layout before any other typewriter.

Five years later (1873), the invention of the “Shift” key was a game-changer that added to the popularity of Remington typewriters with the release of the No. 2 typewriter. This feature allowed for upper and lower case letters used for the vast variety of forms, letters, official documents, etc. now in use by the many new companies that sprouted up from the boom times of the Industrial Revolution.

Another innovation for the Remington No. 2 was the addition of color. Six colors made the selection based on the machine’s capabilities and its color.

Despite its success, E Remington and Sons made the decision to divest of the typewriter business in 1886 by selling it to the Standard Typewriter Manufacturing Company. Standard had a sense for what a good business it had bought, and kept the Remington name on its future iterations of the product.

The Next Generation(s)

Following up on the reputation of its new acquisition, the Standard Typewriter Company changed its business name to Remington Typewriter Company in 1902. Although it had bought the rights to continue using the Remington name, taking it as their company name led to more consumer confidence in their entire product line.

The newly named Remington Typewriter Company also began a training program for those wishing to master the machine. The method was called “touch typing,” and the course(s) were offered to business colleges, universities, and the YMCA. The typist would look away from the keys and type based upon memorizing what key was where using the QWERTY layout.

Women were seen as the main market for this program following a shift in the demographic of users. In 1874, women accounted for less than 4% of clerical workers whereas by 1900, that percentage increased to 75%. By 1901, over half of all the higher-education schools offered standardized “touch typing” courses as part of their curriculum, and by 1915, high schools had begun teaching the method using Remington typewriters.

The release of the No. 10 typewriter in 1908 included a “frontstrike” typing ability, where the keys would strike at the same level of the keys rather than moving the keys in a high, upward motion. This market trend kept Remington at the top of the list for buyers of typewriters. The next re-design came in 1923 when Remington bought Noiseless Manufacturing. Touting their machines as “noiseless” was the result of a design change to the metal cover above the typing keys, allowing it to act as a buffer to decrease the noise of the keys moving and striking the paper. Many well-known people made good use of the Remington Noiseless model – including World War II Associated Press correspondent and domestic military editor Bill Boni.

Remington merged with Rand Kardex Bureau in 1927 to become Remington Rand. It is this company that made typewriters and other office machinery, along with computers, and after that, Remington Electric Razors.

The Great Typewriter Strike

As told by Hartford Courant Columnist Marlene Clark in an article focused on the strike, “the American Federation of Labor (AFL) began organizing workers at Remington Rand in 1934, which set off two years of acrimonious negotiating. It reached its peak in May 1936 when Rand officials fired 19 union activists in Syracuse, Tonawanda, and Ilion, New York.” On May 26, 1936, 1,200 workers at the Remington Rand factory (still known as the Noiseless factory) in Middletown, CT joined the strike.” Among the items listed in a complaint filed on behalf of the company’s unions were the dismissal of union officers and supporters without cause, senior management’s refusal to meet with union leaders, and a 20% pay hike that was vetoed by the company.

Then-company President James H. Rand, Jr. started using what was termed the “Mohawk Valley Formula” to break up the strike – spreading propaganda about the union strikes, rumors about intent, and bashing the union strikers for hurting their families by having no income since they were out of work. The propaganda was also often used to call the strikers communists or anarchists in an effort to make the public hate the union workers.

Rand, Jr. became famous for his use of well-placed PR spreading rumors about union officials and supporters of the union, firing union workers and hiring new workers to take their place (“scabs”), and threatening to close the Middletown plant. The strike got so out of hand that the state and local police had to help keep the strikers from throwing stones at workers and vehicles.

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which has a professional strikebreaker system, came in and tried to help the strikers and Remington Rand to reach a deal. The strikebreakers brought techniques that involved propaganda, and would use missionaries to go to the employees’ homes to persuade them to go back to work.

In 1937, the NLRB decided in favor of the workers, and the board ordered Rand to stop interfering with employee’s unions and the right to organize. After the strike was broken in the summer of 1940, the Middletown plant closed leaving 1,200 employees without jobs. The production of Noiseless typewriters ended in 1952.

After the World Wars, Remington continued to manufacture typewriters and eventually made computers after acquiring Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation in 1950. The Univac I was purchased by the U.S. Air Force and the U.S. Army. Businesses would rent these computers at the manufacturing site since they were the size of a one-car garage and sold for $1 million each.

Remington Rand was then bought by Sperry Corporation in 1955.

Collecting Remington Typewriters, or, Could You Become the Next Tom Hanks?

Now that Remington typewriters, among many other brands, are out of fashion, they have become a collectible. Tom Hanks has a collection of over 250 rare and classic typewriters.

Among the early famous typewriter users was Mark Twain. Twain said in a letter to Remington, “Please do not use my name in any way. Please do not even divulge the fact that I own a machine. … I don’t like to write letters, and so I don’t want people to know I own this curiosity-breeding little joker,” talking about his 1875 Remington. Twain was the first author ever to have a manuscript typed. Other famous users include Agatha Christie, the world famous mystery novelist; Rudyard Kipling, who also made good use of the Remington Noiseless model in his later years; and Gone with the Wind novelist Margaret Mitchell, who used a Remington Portable No. 3.

For collecting purposes, look for something that attracts your eye. Features, color, form, maker, and condition are all important, and having a style that can coordinate with your other collectibles makes good sense. Be sure it is complete and operates (if it is to be used). Look for suppliers of antique and vintage-style ink ribbons and replacement keys. Because of the current trend of making typewriter key jewelry, finding replacement keys today could prove to be a bit more expensive vs. 10 years ago.

Generally speaking, expect to pay between $100 and $300 for an older machine (pre-1950) found “as is.” Those that have been refurbished to top condition can bring anywhere from $800-$1,500 and up. In July 2014, a rough Remington No. 1 sold for nearly $27,000 on eBay. But later Remingtons, including the Standard #10, can be found online for $150 and under, in good working condition. Be sure to take a look at the font used and be sure to take a test run.

Oddly enough, European typewriters are considered more valuable in the U.S. than those made here. Rarity is a factor when buying a vintage or old typewriter with a European maker.

Related posts: