Understanding the Theory of Good, Better, Best – Business of Doing Business – The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles – January 2003

by Ed Welch

There is a theory in the antique trade known as good, better, best. The theory is also known by other names such as low-end, made range, high-end, and quality, mediocre, and junk.

The American Heritage Dictionary defines theory as “systematically organized knowledge applicable in a relatively wide variety of circumstances, especially a system of assumptions, accepted principles, and rules of procedures devised to analyze, predict, or otherwise explain the nature or behavior of a specific set of phenomena.”

The good, better, best theory is used in the antique trade for several purposes. One use of this theory is to sort similar items (Queen Anne Highboys, for example) into categories for setting relative value. Another common use of this theory is to explain why the best examples of any type of antique or collectible sell for many times their value while mediocre examples of a given antique sell for about their value and low-end examples sell for less than they are worth.

Place any antique dealer into a room with a dozen Queen Anne Highboys and ask that dealer to sort the highboys into groups of good, better, and best, and chances are that most dealers will choose the same four highboys for each group.

Place a dealer into a room with one Queen Anne Highboy and ask that dealer to grade that highboy as being a good example of the style, a better example of the style, or the best example of the style, and most dealers will have a difficult time doing so.

The skill required to correctly judge the relative value of one antique in isolation requires much study, experience, and first-hand contact with many examples. The study must come from books on the subject. The experience comes from buying and selling similar examples. The contact with many examples comes from visits to museums, antique shows, and antique shops.

The best source of information on sorting similar items into good, better, and best categories is Fine Points of Furniture: Early American written by Albert Sack in 1950. This book has been through 6 to 8 printings. It is required reading for all serious antique dealers. It makes no difference if a dealer specializes in glassware, porcelain or furniture. The principles of classifying like items are the same.

Albert Sack published an updated version of his book in 1993. However, his earlier book is better suited for teaching the principles of good, better, and best. The 1993 edition can be confusing if one does not clearly understand and utilize Sack’s principles.

I use a modified good, better, best theory as a guide in purchasing inventory. My theory is simple, “The best, and all the rest.” I am willing to overpay for the best, but I underpay for the rest.

I have never lost one cent buying the best. In 1968, I bought an 1861 Colt pistol for $175. The going price for such firearms at that time was between $65 and $125. However, I was able to resell this fine pistol for $350 within two weeks. Keep in mind that at that time fuel oil cost 13 cents a gallon, gasoline sold for 18.9 cents a gallon, bread cost 12 cents a loaf, and I had a good job that paid $42.68 a week. The $175 I made on this sale was a lot of money.

I will pay less than 50 percent of the value for everything else. No dealer can make money paying more than 50 percent of the value on common, mediocre, or low value merchandise. For example, an item that sells for $100 and cost the dealer $50 is almost a break even item. Overhead in the antique trade ranges between 20 and 25 percent. Income taxes are about 18 percent.

The bottom-line price breakdown of an item that sells for $100 and cost $50 is: $50 in cost, $20 to $25 in overhead expenses, and $18 in federal income tax. If you pay state income tax, add another six percent.

The total possible in-your-pocket profit ranges from even money if you live in a state with income tax to a possible $12 under the best of circumstances.

The problem with overpaying for the best and underpaying and for the rest is that this system works best in a depressed marketplace.

A depressed marketplace favors the buyer who has money to spend and is willing to spend that money. Because demand is low in a depressed marketplace, prices are low.

I will use an example from the stock market to help make this point. Around Oct. 9, the stock price for General Motors Corporation dropped to nearly $30 a share. This stock nominally trades in the $50 to $70 range.

One would think that there would have been a stampede to buy General Motors stock at such bargain basement prices. Does anyone reading these words believe that General Motors is going out of business? Does anyone believe that the price of General Motors stock will not recover to its normal $50 to $70 trading range?

The prices of most antiques and collectibles have been lowered by the recent downturn in the economy. The very best antiques still sell but at prices considerably lower than prices of just two years ago. The sale of mediocre antiques and collectibles, which are always hard to sell, has slowed to a crawl. The sale of low-end items has all but stopped.

Dealers, who depend on the antique trade to make a living have two options: buy only the very best and, if you must buy “any of the rest,” do not pay much money for it. Buy cheap!

The only time that low-end antiques produce a profit is when you can sell them for less than their perceived value. In order to sell an item for less than its value, you must buy it for much less than its value.

The only time that mediocre antiques produce a profit is during a rising market. The market is still in decline. Do not buy mid-level antiques that are not price below value.

Cupboard number one is a “good” example of mid 1800 cabinetmaking. However, the cupboard lacks proportions. The cupboard is too wide for its height and the full-size draw in the base contributes to the squat appearance. The hinges are fixed to the surface rather than fitted into the door jams. The cabinetwork is just adequate.*

Cupboard number two is a “better” example of mid-1800 cabinetwork. The proportions are correct. The fancy cutout base and the cookie cutter corners on the raised panels add a whimsical, almost folksy feel to this cupboard. The cupboard is painted green and the trim is charcoal. The problems with this piece are apparent only when you touch the cupboard. It is rickety. The doors do not fit well. The drawer does not fit well. The shelves are loose. The mortising work is sloppy. The cupboard wobbles. These problems existed since Day One. The maker lacked the skills necessary to build a cupboard.

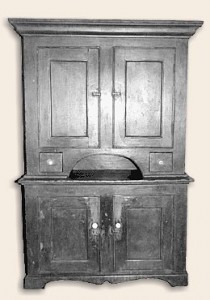

Cupboard number three is an example of the “best” in mid 1800’s cabinetmaking. The proportions are correct. The two silverware drawers and the half moon pie shelf add to the appearance. The cut out base and the moldings are not overdone as in cupboard number two. The cabinetwork is flawless. Both cases are dovetailed, mortised, and pinned. The doors open and close smoothly. The cupboard has been painted blue three times. It is possible to see all three colors in the worn areas.

-

- Assign a menu in Theme Options > Menus WooCommerce not Found

Related posts: