Anyone who has had to help a family member move or downsize, or been left with the responsibility of emptying an estate, knows the heartache of making the hard decisions: what to keep, what to sell, what to donate, and what to throw out. Often, these decisions are made hastily in an effort to get the job done, which does not leave time for the consideration some of these items may deserve.

In 2017, Richard Eisenberg wrote an article for Next Avenue, entitled “Sorry, Nobody Wants Your Parents’ Stuff,” after he and his sister when through their parent’s possessions to determine what to do with them. His article went viral and made a statement about the future of the resale and antiques marketplace that continues to resonate as a statement of fact these many years later.

Family members needing to dispose or downsize the personal effects of a loved one now go into the task believing their cherished items and furnishings have limited resale appeal and monetary value. The result is many look for the most expedient ways to remove and sell off the estate’s items – at any price – just to move them out the door. These items then find their way into thrift stores, consignment shops, yard sales, local auction houses, estate sales, or are sold by dealers who buy up estates and resell the contents in antique shops, online, and at shows.

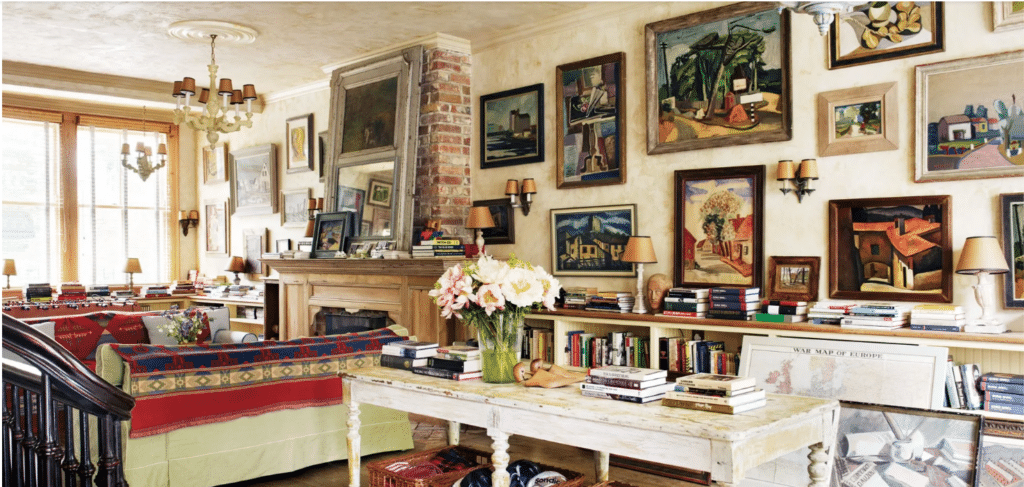

As the saying goes, one man’s trash is another man’s treasure, as episodes of Antiques Roadshow and articles on extreme flea market and tag sale finds continue to remind us. It is why we as antiquers and collectors live for our hobby – the thrill of the hunt. It is also a seller’s worst fear. Sometimes you never know what you had until its value is recognized by a discerning buyer, especially when it comes to artwork, sculptures, and other decorative object d’art. Here, expediency could cost you money.

Eisenberg’s September 20, 2022 article for Next Avenue, entitled “Think Nobody Wants Your Parents Art? Think Again,” suggests that the disposal of art on the walls deserves more careful consideration so something unknown as valuable is not inadvertently trashed. This article provides readers with some thoughts when it comes to art and value– in particular paintings and sculpture – and the challenges to be faced when trying to make a determination on their future.

According to the article, “exactly how much money you’ll receive — if any — will depend on where you look for a buyer and the size, type and condition of the art, and the reputation of the artist.

Also important: is what art people call the work’s “provenance,” or ownership history. Linda Frankel, owner of Artful Transitions, a relocation firm in New York City, says you can verify an artwork’s provenance by having something — a gallery brochure, museum catalog, bill of sale, or letter from the artist — that can establish where it came from, who owned it and why it might have special value.” This will make it easier for you to decide if and where you should sell it.

Fortunately, the internet, a few apps, and Facebook have made it easier than in the past to snag a buyer or donate inherited art. Unfortunately, it’s also possible that auction houses won’t be interested in your art if the artist is unknown to them. Many don’t have the time to deal with artists and works unknown to them, or unknown buyers looking for valuations for possible sale.

For Eisenberg’s article, Matt Paxton, host of public television’s “Legacy List with Matt Paxton” downsizing series and author of “Keep the Memories, Lose the Stuff,” shares: “Auction houses need big names and the reality is you probably don’t have them. But it doesn’t mean [your inherited art pieces] don’t have some financial value.”

Although auction houses might not be interested in your art, somebody somewhere might.

These days, contemporary art created in the 1960s or later is selling well. According to the Freakonomics podcast, the average price of contemporary art has tripled over the past two decades. Paintings generally fetch more than prints. Sculptures tend not to attract buyers as much as paintings because they’re heavier to ship. And generally speaking, if the artist isn’t well-known, then the value of a painting will depend on what’s shown. While most contemporary art in particular will find value in the interest of a buyer based on the image or even colors, every auction house, antiquer, and seller has a cautionary tale to share, as is shared in this article.

One is a story of a woman selling off a warped, moldy abstract painting that had belonged to her deceased father, an artist in the 1950s who’d hung out with artists visiting Cleveland. She planned to sell the painting at a house sale for $50. An auction house representative recognized the artist (Corneille (Guillaume van Beverloo) and its value, and it ultimately sold for $30,000 at auction.

One downsizing homeowner in Oneonta, New York, had a small Picasso sketch Paxton’s appraiser on “Legacy List” valued at about $8,000. Turns out, under the Picasso were two Salvador Dali paintings. The man’s father, the sculptor David Hayes, knew Dali and had traded a sculpture for the paintings, according to a letter Paxton’s team uncovered. Paxton has said the Dalis were sold and “significantly changed that family’s life.”

The article then goes on to share these abbreviated tips for unloading inherited art:

Keep It In the Family. See if a relative wants it. The art may have sentimental value to a sibling, cousin, or other family members.

Do Your Homework. If no one in the family wants the art, research its history and value to see if someone else might. Find the artist’s name if you can; it may be hidden behind the frame or on the back. Then look online to identify the painting and find recent sales of similar pieces. You can do this kind of research on apps like Smartify or websites like Artnet.com, Artsy.net, Artprice.com, FindArtInfo.com and even eBay.

Prepare to Sell. Take photos of the art, artist’s signature, and frame. Measure the frame, too. A frame itself may have value, possibly more valuable than the art.

Get an Expert Estimate. For art you think may be worth more than a few hundred dollars, hire an appraiser to get an estimate of fair market value Appraisers typically charge $250 or more. The Appraisers Association of America and the International Society of Appraisers sites have membership directories that let you search by specialization.

Enlist an Expert Seller. If you have a work by a noted artist or reason to believe you have one or more pieces worth more than $1,000, consider using an auction house to find a buyer. You can look for one in the directory on the National Auctioneers Association website.

Sell It Yourself. To sell art online yourself, experts say Facebook Marketplace is a good place to start. You can quickly see what similar pieces sell for, and by posting photos of your art and your price, you’ll know quickly if there are potential buyers.

Related posts: