by Judy Gonyeau, managing editor

Imagine trying to gather all the grains of sand before the next wave hits the beach and takes them all away. This was the mission Bill Blackbeard (Am.,1926-2011) set out to do by gathering old and current newspapers before they were thrown out. There were hundreds of thousands of newspapers out there waiting to be rescued that contained the gold Blackbeard hunted for: those colorful creative Sunday Funnies.

A Focused Collector

According to The Comics Journal, Bill Blackbeard had his “a-ha!” moment at the age of 12 when he looked in a neighbor’s garage and saw a massive amount of old newspapers stacked high along one wall. The colorful double-spread Sunday comics drew his eye and he started to explore what was there. Stacks and stacks of newspapers dating back to 1923 grabbed him into its clutches. “I was absolutely excited at this stuff,” Blackbeard told reporter Kevin Parks in a segment for This Week News, who noted that “his voice still brimmed with wonderment.” The owner of the garage came home while Bill was still there and indicated that he wanted to rid himself of all those heaps of newspapers – “that was all Blackbeard needed to know.” He hauled them off and started his collection of comic strips.

William Elsworth Blackbeard was born on April 28, 1926. When he was 12 in 1938, Action Comics #1, aka the introduction of Superman, was hitting the streets. Blackbeard was known to have very strong feelings about comic books, saying, “Far from being overwhelmed when Action came out with Superman, I thought it was meretricious dreck. I liked the art. I’d been following Slam Bradley in Detective Comics. And I liked the storyline; I thought that was fine. But the Superman content did nothing for me because I immediately saw what many other people saw: there’s no story here. If he can do anything he wants to, who cares? Why bother? But the art did appeal, and I looked at it occasionally. It was nicely drawn. … I couldn’t understand how anyone would want to immerse themselves in such stuff. I was definitely not a sympathetic reader of the early comic books. I had dismissed them growing up. It wasn’t until the comic book craze of the sixties came in that I thought, My god—people think this is classic! Couldn’t believe it.”

Blackbeard became much more of a realist than a fantasy-seeker. This trait was a benefit as he stayed focused on comic strips. As Parks noted, “Blackbeard aspired to acquire every strip ever published.”

Before the Newspapers Disappear

After graduating from high school and serving during World War II, Blackbeard started earning a living by becoming a freelance writer by day, and comic strip collector by night. This continued at a fast pace until the early 1960s when a now middle-aged writer and collector discovered that libraries everywhere were putting newspaper content onto microfiche or microfilm and then throwing away the newspapers.

There were two problems with this: one, the microfilms were subjective to who was clipping through the paper and often did not include comic strips; and two, if they did include them, they were now shown only in black and white and a series was more likely to be incomplete.

In order to accept the newspapers from the libraries—which were more than happy to give all this “clutter” to this new collector—Blackbeard had to establish a non-profit. To get the donation, Blackbeard established the San Francisco Academy of Comic Art (SFACA) in 1968, calling it “the fastest thing I’ve ever done.” The donations came flying in.

At this point, he and his wife, Barbara, were living with his growing collection. Many of his friends noted that they barely had room for their bed in the bedroom, and the only place without comic strips was the bathroom due to the humidity. By establishing the non-profit, they then moved into larger and larger living spaces (aka storage room) by guaranteeing that the content of the entire collection would be available 24/7.

The large cadre of newspapers being donated resulted in a good deal of manual labor, paging through each paper, then stripping out the comics sections, and then getting rid of the rest of the paper. Afterward, the comic strips were put together to show an entire story that ran over many days. Entire Sunday Funnies sections were maintained as well.

The Big Hit

Unhappily, he discovered that many of the Library of Congress volumes had already been microfilmed and discarded before he could get them. Blackbeard then scoured the country for libraries willing to give him their bound files as they microfilmed the newspapers into posterity and oblivion. “Many libraries didn’t care who I was,” Blackbeard said. “Just take the files off our hands, they said. And I would go in and physically take them and truck them back here to San Francisco. And they thought that was wonderful because they didn’t have to hire someone to do it. So, I had Ryder trucks trundling all across the country – from Chicago, from New York, from the Library of Congress.”

Where did the Money Come From?

Blackbeard and his wife lived simply without many needs. The dedication—and space—given to the mission of creating a complete assemblage of comic strips was immense, but so were some of the costs involved. Rather than seeking monetary donations or pursuing grants, Blackbeard wrote and edited a plethora of books and articles that became the foundation for the reference materials needed about this topic and were non-existent when he was conducting his early research.

In the mid-1960s, Blackbeard hatched an idea: he wanted to write a formal history of the American comic strip. He’d grown up on Floyd Gottfredson’s Mickey Mouse and E.C. Segar’s Popeye (i.e., Thimble Theatre), “so I had been exposed to the best,” he said. With this book, he wanted to immortalize the immortals. He pitched the idea to Oxford University Press, and his project was approved. But then, he was stymied by the absence of available primary resource material. The book was never written.

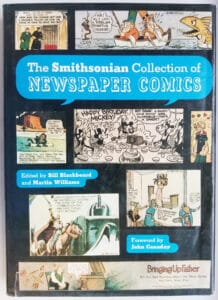

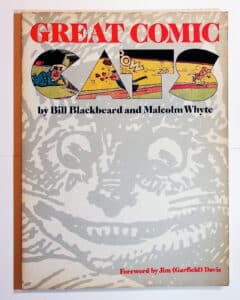

That did not stop the determined comic strip historian from his mission to share the knowledge he was accumulating. One example of his literary prowess happened in 1977 when Blackbeard and Martin Williams edited The Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics. This book, much like his collection, was “a huge, gorgeous, massive, and beloved tome that stands as a testament to the lasting cultural and artistic importance of the newspaper strip,” according to Jeet Heer, an Indian-Canadian author and comics critic. Over the years, Blackbeard edited more than 100 books based on his material from the collection.

Blackbeard’s writing tended to be academic in style with flashes of playfulness in the form of puns, side stories, and somewhat long information-filled paragraphs that “wound around and eventually come upon themselves going in the opposite directions. His prose was the work of a man who loved the written language, and reading it made the attentive reader smile gratefully,” according to The Comics Journal. His writing endeavors were what went to pay the bills and build the collection.

Blackbeard also funded his mission and modest lifestyle by selling copies or duplicates of comic strips as well as reproductions of pulps to collectors and researchers.

The Collection Saver: Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum

In 1997, Blackbeard sold his entire collection to the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum at The Ohio State University. Curator of Special Collections and Area Studies Jenny Robb penned “Bill Blackbeard: The Collector Who Rescued the Comics” in the Journal of American Culture, 2009. The paper not only describes the lifelong passion behind the Blackbeard collection but also talks about the process of taking on the task of gathering all that paper in a short amount of time. Here is a taste of the task at hand:

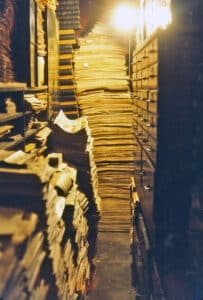

“In early January of 1998, a team of movers arrived at 2850 Ulloa Street in the quiet residential neighborhood known as the ‘Sunset District of San Francisco.’

“Inside, they discovered that the unassuming Spanish stucco home was literally filled from top to bottom with paper material of all shapes and sizes, books, magazines, comic books, pulps, story papers, prints, drawings, and, most importantly, newspapers, bound newspapers, individual newspapers, newspaper tear sheets, and newspaper clippings. The massive collection filled most of the upstairs rooms and the entire spacious, ground-floor garage below that ran the length of the building. The immense garage was a maze of narrow alleys created by floor-to-ceiling stacks of bound newspaper volumes and individual tear sheets, boxes, and file cabinets containing millions of comic strip clippings; and rows of shelves made from crates turned on their sides to house books and periodicals. For decades, the building also served as the residence of the man responsible for collecting this mass of paper, Bill Blackbeard. Blackbeard was living there with his wife, Barbara, and more than 75 tons of popular culture material when he learned in 1997 that the home’s owner would not renew his lease.

“Recognizing that the collection, known as the San Francisco Academy of Comic Art (SFACA), would have to be moved, Blackbeard began negotiations with Lucy Shelton Caswell, then curator of The Ohio State University Cartoon Library & Museum (then called the Cartoon Research Library). Caswell and Blackbeard eventually agreed that the materials should be transferred to Ohio State. The movers faced the daunting task of packing the entire collection to be shipped across the country to its new home. It was by far the largest collection ever acquired by the library and is one of its most important for the study of popular culture in general and graphic narrative – or sequential art in particular. Blackbeard’s story demonstrates that individual collectors have played a particularly critical role in protecting and preserving our popular culture heritage, a heritage that, until relatively recently, was largely ignored by established academic institutions.”

To date, a little more than half of the collection has been curated with much more work ahead. Without Bill Blackbeard working with the Museum, this important archive of comic strip history and commentary may have been lost to landfills.

To learn more, visit the collection, or learn more about this important Library and Museum, visit https://cartoons.osu.edu/

Related posts: