Exploring Antique Technologies

by Kary Pardy

The river that flows two ways, the river of tides, the Great River of the Mountains – The Hudson has inspired countless artists and dreamers but is more than just a muse. From the early 17th century to the present day, the Hudson River served as a passageway into the northern and western territories. Countless ships traveled her rolling waters, and even more goods and passengers found their way through New York City and beyond on this historic highway.

The maritime history of the Hudson is filled with discovery, ingenuity, and opulence, and studying the river takes one through several key moments in American history. Should this appeal to you, consider diving a little deeper into a Hudson River maritime collection, one based on the fascinating history of New York’s great river.

The Hudson River Maritime Museum in Rondout, NY preserves exactly what its name implies and, in 2000, history professor Robert Panetta working with Ellen Keiter, the museum’s curator of exhibitions, staged an exhibit called Boats on the Hudson: Navigating through History. In eight boats, they explored the transitions seen on the river from the dugout canoes of the natives and Henry Hudson’s initial trip in 1609 to today’s freighters. Let’s take a similar approach, and appreciate the river’s history through the ships that sailed her lengths.

Styles of Transportation

The Hudson was thin and filled with tricky sandbars, and the first sailing vessels to make headway were sloops, agile, one-masted sailing ships that dominated river travel into the early 19th century. According to Panetta, in 1832 there would have been approximately 1,200 sloops sailing at once. It was crowded.

There wasn’t much change to the scenery until Robert Fulton’s wave-making invention took off. In 1807, Fulton debuted his steamboat, the Claremont. She took passengers from New York City to the important port of Albany, NY in record time. While sloops took up to a week to make the trip, Fulton’s steamboat did it in little more than a day.

The Hudson was a busy passage, a north-south route that transported passengers, cargo, and sightseers throughout the day and night. In 1825 the Erie Canal opened, and for the next couple of decades, the river was the main artery of trade and travel in the north. It was the number one passage north and a primary means of traveling west. Accordingly, the Hudson River Valley was the population center of America, and steamboat travel was enticing to tourists and transporters alike.

Moving Goods

Steamboats broke into the trade market first with perishable goods. Their speed could not be beaten, and they, or their attached barges, carried what the slower sloops could not, while the sloops moved building materials and more sturdy freight. The sail was still the cheapest method around, but larger schooners coming in from the ocean would need a little assistance, and collectors may find images of schooner flotillas being pulled down the river by steam tugs. They could not navigate with as much dexterity as their sloop cousins. Hudson River sloops were used to carry freight until the end of the 19th century when steamboats became cheap enough to replace them. Lovers of sloops can still see replicas on the river, or find them immortalized in Hudson River School paintings.

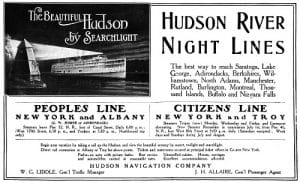

The jewels of the mid-19th century, however, were the steamboats. By 1850, steamboats dominated river travel. The best-known steamer company, the Day Line, also offered a Night Line, to accommodate tourists and business travelers alike. Steamships were luxuriously appointed, and like one of the most famous examples the “River Queen” Mary Powell, they offered Victorian opulence and a romantic travel experience. They also aided in the war effort. During the Civil War, the Day Line and Night Line transported hundreds of thousands of soldiers to muster at Albany and then took them to New York City and onward to battlefields in the south. Soldiers in uniform traveling to or from the war traveled for free.

Other Modes of Transportation

Passenger steamships, though popular, found competitors in the new trains that cruised up and down the New York shore. Railroads were faster and novel, but steamers epitomized taking the scenic route; they were clean, comfortable, and presented non-stop sightseeing opportunities. Railroads might get you where you needed to go, but taking a trip aboard a paddle wheeled steamboat was a diversion in itself. Steamers continued transporting tourists well into the 20th century.

Steam power also fueled Hudson River towing, a big business for most of the 19th century and on into the 20th. Steam tugs started as retired passenger ships, but in the second half of the 19th century, dedicated steam towboats developed for pulling boats or barges down the long stretches of the river. These are the tugboats that we know today. The principal towing company, Cornell Steamboat Company located in Rondout, NY, pulled freight from the 1880s until 1930.

If you were to step onto the shore of the Hudson River in the mid- to late 19th century, you would see a busy channel filled with maritime commerce. From sloops to large, fanciful passenger ships to tugs pulling cargo, the river was bustling with activity. The 20th century brought the decline of sloops and showy steamers, replacing them with self-propelled freighters and ferries. Ferries crossed the river and stood in until a series of bridges were constructed in the 1920s and 30s to span the river at key points. Today’s river is host to freighters, tugs, guiding pilot boats, a few ferries and pleasure cruise ships, and an array of recreational boats. River shipping is not as dominant as it once was, but you can still see large cargo ships from all over the world navigating the Hudson’s finicky sandbars.

“These may include ephemera and memorabilia from Hudson River boats, historic photographs, letters and manuscripts, ledgers and receipts, and historic books as well as larger objects such as ship name signs, parts of Hudson River ships, model ships, tools, and materials relating to Hudson River Valley industries such as brick-making, ice harvesting, bluestone quarrying and carving, boat building, etc.”

Clearly, there is a wide variety of Hudson River maritime collectibles floating about. Should the history of the ships in those famous paintings interest you, I encourage you to do some digging of your own. Hudson River specific memorabilia command respectable prices due to historic import and demand. You may well find a story or a ship that calls to you, such as the Mary Powell. The fastest passenger ship on the river for around 55 years, Mary carried General Custer’s body to his final resting place at West Point after his Last Stand, and Walt Whitman wrote in 1878, “On the Mary Powell, enjoy’d everything beyond precedent … constantly changing but ever beautiful panorama on both sides of the river (went up near a hundred miles).” No matter your ship of choice, options for collecting the historic Hudson River extend far beyond its namesake paintings.

Related posts: