by Mike McLeod

Just imagine a world—if you can—in which the process of weaving was never discovered. Without weaving, people from the beginning would have been wearing leather all year long or grass skirts or fig leaves, probably until cardboard or plastic was discovered.

Early Stages of Weaving

Throughout the ages, weaving has been used to make life better. In addition to clothing, weaving created shelter, fences, bedding, footwear, art and so much more. When you contemplate all the facets of life that were built upon or rely upon some form of weaving, one gains a greater appreciation for this simple but often intricate art.

Take fishing, for instance. Without nets, the quantity of fish that could be taken one at a time with a line would only support a family or two. Nets were needed to help feed a village, and thus, this allowed the population size of towns near the seashore and rivers to grow.

Without woven canvas sails, fishing would be limited to how far a canoe could be paddled or a boat rowed. There would have been no large sailing ships for exploration of the world or trade. Even Viking longboats relied on sails more often than rowing for long voyages. Continents separated by oceans would have remained mostly isolated until the age of steam power.

Fortunately, people all over the world from the earliest times had the weaving epiphany and realized they could weave palm fronds or grasses by hand into the necessities of life for warmth, protection, and comfort.

Innovation of Fabric

The next epiphany that followed was thread being twisted or spin from twisted plant fibers first and then from animal hair and hide. Later, thread and yarn were spun from wool, cotton, and linen. One of the oldest dresses made of linen still in existence today is the Tarkhan Dress, which was found in the Tarkhan Cemetery in Cairo, Egypt, in 1913. It is believed to be 5,000 years old.

Around the 6th century came the exciting discovery of silk thread – its sheen and ability to take color. Byzantine craftsmen would weave the silk into brocades, damasks, and tapestry-like fabrics. Brocades were woven by hand on large looms called draw looms. The weaver would call out to the draw boy to tell which threads to lift and when to put the right color thread in the right part of the pattern. By the end of a full day, the makers may have completed two square inches of patterned silk cloth.

The Jacquard Loom

Jump forward in time from when the linen cloth for the Tarkhan Dress was first woven to the 18th century, to the time when weaving played a central role in the development of the first computing machines. In 1725, Basile Bouchon created a means for controlling a loom by using holes punched in sheets of stiff paper where threads would be fed through—a bit like programming an early computer—to aid in formatting color and design within the woven piece.

In 1804, Joseph Marie Jacquard applied this method to his own creation, the Jacquard loom machine. Jacquard’s machine was very successful, and many imitated his design from then on into the 20th century. Basically, cards punched with holes controlled which strings were raised on the loom. This not only sped up the work, but it also made the creation of highly intricate designs in material possible, such as brocade, florals, damasks with their reversible fabric figures, paisleys, and quilted or padded matelassé.

Jacquard was not the only inventor to see the usefulness of the punch card for controlling machines. In 1890, Herman Hollerith utilized the punch card system to program the movements of a calculating machine he built. His successful company would later become known as International Business Machines or IBM.

J.M. Jacquard’s machine had punch cards stitched together in a chain to present them to the loom one at a time. Control rods were then either pushed through the holes in the card or stopped by the lack of a hole, leaving them in place. The stopped rods were then lifted up, raising specific warp heddles and the strings attached to them. (Warp strings run up and down on a vertical loom, like longitude lines; the weft is side to side, like latitude.) To get a better understanding of this process, search on YouTube: “How was it made: Jacquard weaving.”

Each punch card controlled the work on one row at a time and wove the design into the material as it was made. Imagine the number of punch cards needed to weave a finely designed tablecloth or bolt of cloth. In the accompanying photo, 24,000 punch cards were used to weave the portrait of J.M. Jacquard in silk.

The whole process of setting up and operating a Jacquard loom may seem like a Herculean effort, and it was. Weavers know how tedious it is to restring each heddle on a regular loom to set it up for weaving (and for those who want an overview of the loom, visit YouTube for a variety of demonstrations, including one called Weaving on Mount Vernon’s 18th Century Loom, a fascinating look at historic weaving). Comparatively, that was almost child’s play compared with setting up a Jacquard loom. First, a machine like a typewriter was used by a highly experienced designer to punch holes in code into hundreds or thousands of cards to create the design. Next, the cards were chain stitched together. Then, the cards were attached to the loom.

Despite the great effort required to set up and run them, Jacquard looms streamlined the work of the weaver and mechanized at least half the job. This increased production of textiles with highly intricate and complicated patterns, which generated great profits.

Tapestry Illustrating History

As the talents of weavers progressed in the early years, their handiwork also progressed into works of art: Persian rugs, Navajo chiefs’ blankets, medieval tapestries, Peruvian textiles, and more.

During the Middle Ages, collecting outstanding tapestries became popular among the nobility. The skill and artistry of those medieval weavers cannot be denied. They created intricate, colorful, and sometimes gigantic pictures or designs in tapestry. Kings, aristocrats, and church leaders who could afford such luxurious textiles paid handsomely to have their conquests in battle and in life to be woven into historical records.

The use of tapestries in castles, churches, and manor houses most probably began as insulation from the cold. Soon, some medieval interior designers realized hanging tapestries on walls could be both functional and artistic at the same time.

Tapestries were also excellent media for exhibition; they could be rolled up, moved, and displayed at festivals, celebrations, royal weddings, affairs of state, and when visiting other kings and nobility. Imagine trying to transport a life-size, rigid masterpiece on canvas to a neighboring kingdom on horseback or by wagon without damaging it? Shudder the thought.

The Royal Collection Trust website (RCT.uk) records: “For many centuries, tapestries were the primary decorative form at the royal court, far exceeding paintings or other works of art in status and expense. Their acquisition and use are closely linked to the history of court spectacle and to the furnishing of the royal residences. … Over 2,450 tapestry wall hangings were listed in the inventory taken after Henry VIII’s death in 1547, and when they were valued for sale during the Civil War, many were priced at thousands of pounds – far more than any other item in the collection.”

Elizabeth I displayed her tapestries when receiving foreign dignitaries, as did most royals, to impress their visitors and create a “… majestic atmosphere suited to royal activity,” according to the Royal Collection Trust.

Tapestry art was also used to teach Bible stories and religious values in churches and elsewhere. George Washington Vanderbilt II’s Biltmore House in Asheville, North Carolina, has a tapestry gallery that includes three masterpieces from The Triumph of the Seven Virtues collection. As Biltmore.com states, the tapestries were created in 1525-1535 by unknown weavers in Flanders (now Belgium). The tapestries depict a complex multitude of people, animals, and scenes symbolically representing the virtues of faith, charity, temperance, prudence, fortitude, chastity, and justice.

Quite boggling to the mind and to the eye is the fact that tapestry art was often executed on a grand scale, such as those in the Biltmore. One of the greatest in scale is The Apocalypse series of tapestries which measures 6 meters high and 140 meters long; it depicts 90 scenes from the Book of Revelation. These tapestries were created for Louis I, the Duke of Anjou, in Paris in the later 1300s. Such epic works of art required many weavers with several working at the same time on the same line in the tapestry, each assigned about a meter in width to weave.

Photo by Gribeco, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Tapestries in Medieval Europe were the dominant artform of the well-to-do, and that carried forward over the centuries. “Until the 19th century, tapestries were often ordered in Europe by the ‘room’ rather than by the single panel. A ‘room’ order included not only wall hangings but also tapestry weavings to upholster furniture, cover cushions, and bed canopies and other items,” according to Britannica.com.

To assist weavers, artists were hired to draw “cartoons,” not those we are familiar with but drawings of the actual pictures to be woven into the tapestry.

Plenty to Collect

For collectors, weaving is one of the broadest categories with possibly the most types of items available. A brief list includes:

• All periods and styles of clothing – and it doesn’t have to be Marilyn Monroe’s Subway Dress that sold for $4.6 million or Dorothy’s Wizard of Oz blue gingham dress that went for $1.56 million.

• Basketry – Shaker, Longaberger, Native American, and baskets from pretty much every country and culture.

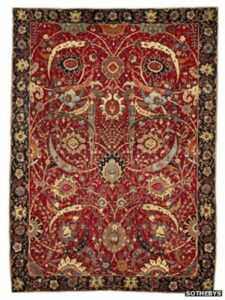

• Rugs – from Persian to Peruvian. The most expensive rug sold to date is the Sickle-Leaf carpet from the Clark Collection that was auctioned for $34.8 million in 2013 at Sotheby’s; it was woven in the 17th century and measures approximately 8 feet 9 inches by 6 feet 5 inches.

• Modern and antique tapestries

• Mid-Century upholstered chairs

• Even different types of handlooms, from lap looms to 45-thread looms and beyond.

A Weaver’s World

From one point of view, it could be said that it is a weaver’s world. Now and throughout the ages, something woven has always been nearby, and most often, it is touching us. Very few fields of collecting can say that – if any.

“You’re welcome,” says the weaver.

Related posts: