Philip R. Goodwin

By Judy Gonyeau

Manifest destiny drove men and women into the wilds of the west, with many fine artists and illustrators delivering promising scenes of great beauty and seemingly unlimited resources ready to be captured and used to make life as pristine as the bubbling water. The utter romance of this western utopia also included the pulse-increasing dangers of the wilderness with its unknown elements and wild animals roaming the land. The combination of beauty and danger created the palette for illustrators working with manufacturers supplying goods to frontier men and women exploring the West in the late 1800s and early 1900s. One such illustrator was Philip R. Goodwin, whose illustrations of the great outdoors reached more homes than any other illustrator of his time – and perhaps of any time.

Philip R. Goodwin

Born in Norwich, Connecticut on September 16, 1881, Goodwin showed an artistic ability from an early age, selling his first illustration to Collier’s magazine at the young age of 11. By the time he was 18, he had attended the Rhode Island School of Design and the Art Students League in New York, and then met the artist who would have the greatest influence on his artistic style and methodology, Howard Pyle (1853-1911). Goodwin studied under this icon of illustration at Drexel and later at the Howard Pyle School of Illustration Art from 1901-1903.

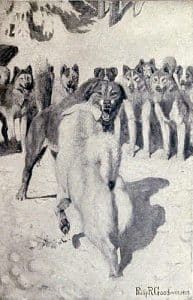

At the age of just 22, Goodwin was hired to illustrate what would become one of the most iconic books about the wilderness: Jack London’s The Call of the Wild. The following year he illustrated Theodore Roosevelt’s African Game Trails. At that time, he opened his own studio in New York City, where his reputation for contributing outstanding work for publications including the Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s Weekly, Outdoor Life, Outing, Scribner’s Magazine, and Everybody’s continued to grow and prosper throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

Philip Goodwin had a fascination with the West, especially after seeing the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show as a child with one of his uncles. He focused on all the excitement and striking visuals that came with the Wild West – wildlife, cowboys, Indians, hunting, fishing, and the wilderness. Thanks to his work with Howard Pyle, Goodwin understood the importance of real-life experiences within the subject he was illustrating to gain a greater empathy with the environment of the subject. He was friends with Carl Rungius, an avid outdoorsman who taught Goodwin about survival out in the wild. Close friend, mentor, and fellow illustrator Charles Russell invited Goodwin to his Lazy KY Ranch and Bull Head Lodge, and traveled with him on painting, fishing, and hunting expeditions throughout the West. While Russell worked with Goodwin on his animals and color palette, Goodwin worked with Russell on atmosphere and space. Russell had not painted en plein air (painting from life in the outdoors) until Goodwin started painting with him and shared Pyle’s approach to “living in” the painting.

It was during a six-week trip in 1911 deep in the Canadian Rockies with fellow artist Carl Rungius that Goodwin had an encounter that would play a role in some of his most famous work. Rungius had reminded Goodwin to bring his paintbrush and his rifle when they went out to paint and sketch, saying “you’re bound to run into game on the day you don’t.” Sure enough, Goodwin forgot his rifle and looked up to see a Grizzly coming up from a river only 40 feet away. The two stood at the same time and stared at one another for a moment before both turned and ran in opposite directions.

That unexpected moment of man vs. bear served as fodder for a number of his paintings often referred to as his “surprise” or “predicament” paintings. Goodwin was also good friends with Will Rogers, Ernest Seton Thompson, and Theodore Roosevelt, adding to the colorful references he utilized when he was depicting life in the Great Outdoors.

Time Marches On

Goodwin never married and stayed dedicated to the health and well being of his mother. She passed in 1924, causing him to go into a period of despair that was compounded in 1926 when his good friend Charles Russell died. In the great depression, Goodwin’s bank failed and he was barely able to keep his studio going. Over the next few years, he began to re-think his location and made plans to move to California and live with his brother and his brother’s family. He was finalizing plans when his body was found in his studio, his lifelong canine companion at his side. He was stricken with pneumonia and passed away a few days later at a hospital in 1935 at the age of 54.

Goodwin’s formative education took place at the dawning of America’s Golden Age of Illustration. Contemporaries included N.C. Wyeth, Thornton Oakley, Maynard Dixon, Carl Rungius, and Frank Schoonover. His early foray into the world of commercial illustration gave him the contacts he needed to secure work to maintain his studio and grow his talent. Even as he just opened his studio in 1904 following the illustration of The Call of the Wild, Goodwin was invited to join the oldest professional art organization in America, the restigious Salmagundi Club.

While his name was never considered “household,” Goodwin’s work was seen by more Americans than either Charles Russell or Carl Rungius because of his lifelong relationships with so many magazines and advertisers. Godwin’s artwork was reproduced on calendars, in advertisements, on the pages of many popular magazines, and tied to such iconic names as Winchester, Remmington, Marlin, and more.

Philip Goodwin’s illustrated calendars were published by Brown and Bigelow – the largest calendar publisher at that time. The large amount of ephemera generated during his lifetime made him the “most famous Western illustrator no one has ever heard of,” according to past-curator of art and Western heritage at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon, Texas. “He literally reached more people through his art than any other artist in U.S. history.”

The paintings, prints, and ephemera produced also included a famous watercolor sketch of a cowboy riding his galloping horse while holding his Winchester rifle that was completed in the summer of 1911 and became the logo for Winchester; however, while Phillip R. Goodwin first rendered the Horse and Rider back in 1919, it wasn’t until 1965 that Winchester finally got around to registering it as an official corporate trademark.

Value on the Market

According to mutualart.com, Philip R Goodwin’s paintings tend to sell well above estimate at auction. An oil painting on board showing two men in a canoe (date unknown), 8″ x 10″, sold for 233% above estimate, $5,000; and The Golden Girl of the West (1914), a 31 1/2″ x 24″ oil on canvas, sold for 129% above estimate, $137,500. Moose Hunters, a 36″ x 25″ oil on canvas sold for $128,000 at a recent Jackson Hole Art Auction

Goodwin’s watercolor and pencil studies for his paintings are also climbing in price. A 4″ x 5″ watercolor sketch on paper simply named Calf (1894) reached 40% above estimate to sell for $3,510 at the Jackson Hole Art Auction, and 11 pencil/pen and ink/watercolor sketches sold for 411% above estimate in 2013 – perhaps a sign of things to come. His art rarely goes below estimate and continues to climb in value.

Related posts: