An Interview by Judy Gonyeau, managing editor

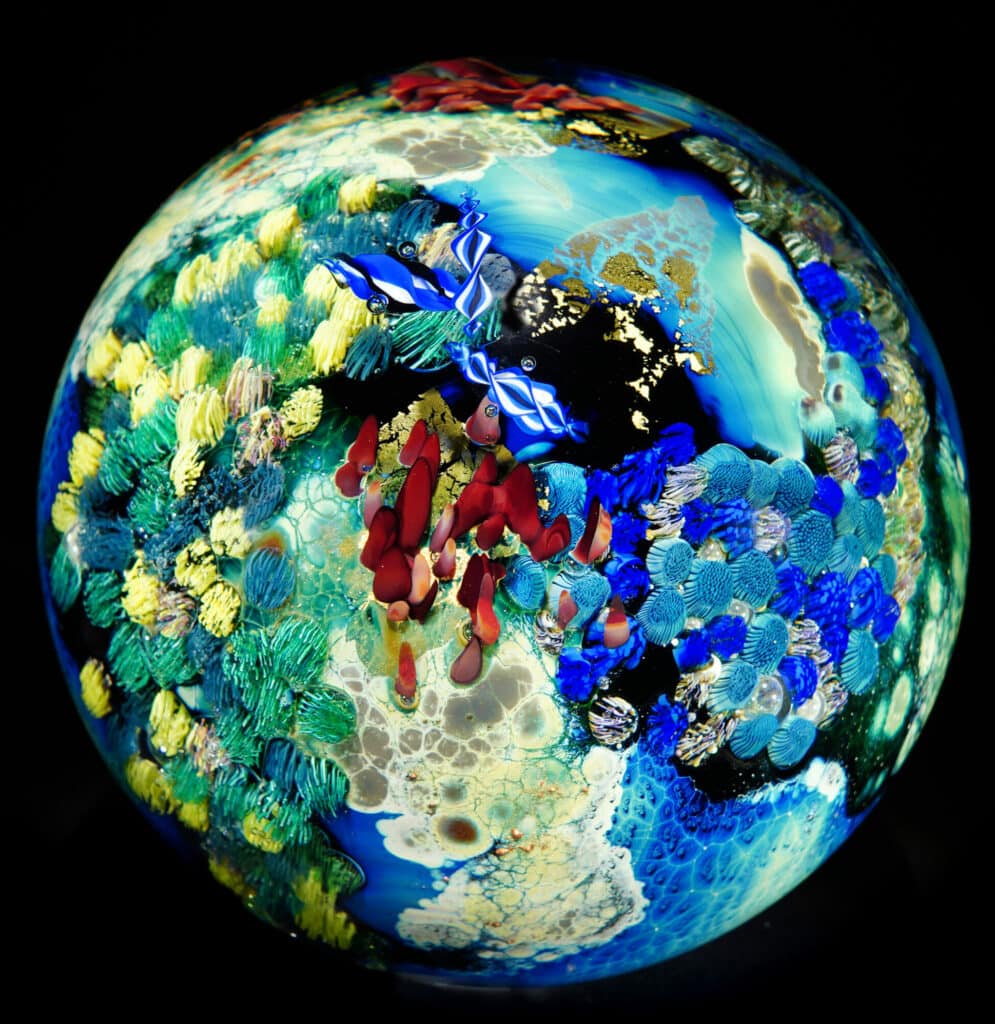

Our Earth, which seems so limitless, is really only a tiny little blue marble floating in the black void of space. Our planet, which seems so infinite, has to be treated with kindness and respect. That’s where the making of Planets started.

– Josh Simpson

Josh Simpson to Ground Control

Even after reaching his 50th year of creative glass work, Josh Simpson is on a roll. In his Artist Statement, Simpson sums it up this way:

“Glass has held my attention for 50 years now, which is amazing because I have interests that scatter me in many directions. … When it’s hot, glass is alive! It moves gracefully and inexorably in response to gravity and centripetal force. It possesses an inner light and transcendent radiant heat that makes it simultaneously one of the most rewarding and one of the most frustrating materials for an artist to work with. Most of my work reflects a compromise between the molten material and me; each finished piece is a solidified moment when we both agree.”

Space is hardly a final frontier for Simpson. Space, atmospheric phenomena, color, form, function, mechanics, chemistry, exploration, physics, laughter, the sky, friends, and family provide him non-stop inspiration every day. Simpson is entering the third quarter of a century of using his own formulas for glass and techniques that go beyond the usual—yet not far from the ancient—to make Planets, spheres, sculptures, and more. “What delights me about these objects that I make is they transcend race, culture, and religion. Everybody gets it. Every viewer in essence (becomes) a small child when they pick up a little marble or one of my Planets. It’s a little world that you can see inside. … I have photos of people from all walks of life holding Planets and they see a wonderful little precious thing. Everyone understands them, no matter what their political or religious leanings are, or their gender, age, or ethnicity.”

Part Creator, Part Chemist, Part Engineer

Back in 1971, Simpson was majoring in Psychology at Hamilton College in Clinton, New York, when he fashioned his own opportunity to experience glass blowing. “I’d seen a glass studio at Goddard College when visiting a high school friend who was a student there, and it looked incredibly fun. So, for the January term of my senior year, I somehow convinced the Dean that there was some sort of academically redeeming value in my blowing glass at Goddard for a month. And bless him, he let me go.” Then, Simpson quit school (with only one course remaining between him and a diploma!) and moved on to Marshfield, Vermont, to establish Burnt Mountain Glass. “I dropped out of college and rented 50 acres of land in northern Vermont for $22.50 a month. On that land, I sewed a teepee to live in and then, using recycled and found materials, I built a tiny little studio that was 12’ by 12’ by 12’. That’s where I taught myself to blow glass.”

Simpson had a natural affinity for glassmaking thanks to his up-bringing. “My dad was very cool about letting my two brothers and me use all the tools and equipment, chemicals, and even gunpowder we could find to experiment with. The fact that my brothers and I are alive at all is miraculous.” Exploring how things interact to cause a reaction became the foundation for so much of Simpson’s work. It became ingrained in his psyche.

What his informed curiosity also gave Simpson was control. Control over what he used, what he built, and what goes into each piece. He is still trying to replicate a formula for his Corona Glass that he first developed in the 1980s. At this point he is nudging the proportions of metallic oxides in the mix by the smallest amounts, hoping the next formula produces a proper reincarnation of the original. I saw a piece of paper with some values and numbers on it.

Here’s how Simpson describes it:

“That is the Corona Glass formula that I’m currently experimenting with. It’s formula 390 [i.e. the 390th formula for the Corona glass] and it’s in the furnace right now. But here is formula number 389 from a few days ago. This trial turned out to be predominantly red. Sand, silver, oxide, nickel, and feldspar … all those minerals and metals combine in unpredictable, delightful ways, and sometimes create amazing colors.”

Talk About Color!

Over the 50 years Josh Simpson has been making his glass objects, there is glass from his past placed in every one of his pieces. The inventory of cane glass used to create the breathtaking variety of color and form within his Planets comes from a multi-decade, carefully curated inventory. On any given day, Simpson can add cane glass segments he created 30 years ago as a part of his current project.

“I have a whole palette of colors in my ‘quiet’ studio There are literally thousands of colors—greens and purples and pinks and reds—that I’m working with right now.

“The process of pulling cane is really quite involved. We sometimes start with a bar of densely colored glass that I’ve gotten either from Germany or from New Zealand. These are colors that I don’t want to create myself in bulk here in my studio. Instead, I can buy them by the kilo and can use just what I need as I need it, and not have to fill my own furnace with bright orange, for example. I can still shape or twist it to make it even more interesting. … I keep all these little unique pieces and use them for when we’re making a series of Planets.”

Collecting Simpson

Many people who collect the work of Josh Simpson are within the New England region because Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts is where he makes his home and does his work in the barn he converted into his studio.

Simpson’s glass is part of the permanent collection at the Corning Museum of Glass, the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Museum, the Yale University Art Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and many more museums. The list of exhibitions, from New England to the White House and beyond shows his appeal to any explorer of art. He even had two of his own PBS specials.

The availability of his objects is carefully curated at his studio. And perhaps the best place to view his work is at his website, www.joshsimpsonglass.com. Here, you can almost fully experience the excitement of exploration when you see any of his work. The flow and color and details draw you in. The best way to see and handle and purchase his work is to visit his nearby Salmon Falls Gallery in Shelbourne Falls, MA. To feel the coolness of the glass, its weight, and truly see the detail is worth the trip alone.

“One day in 1976, I discovered several handmade glass marbles in the old garden bed outside my kitchen door. Probably left there by children a generation or two earlier. When I washed them off, they were still just as bright and vibrant as they’d been on the summer afternoon they went missing.

“I thought about how many priceless glass objects now in museums were originally lost for eons until dug up by archeologists. No museum had yet shown my work and I wondered … what if no one ever did!? But I was making glass Planets that would probably last for centuries. So I thought, ‘Why not bury some of them, and perhaps someday a future researcher might find one. Perhaps that small planet would become an enduring mystery to confound the experts, and this way my glass might even find its way into a museum after all!’ (I even hid a Planet right outside the Corning Museum of Glass. Found by Director David Whitehouse, it is now in their permanent collection. My plan worked!)

“Eventually, I started leaving Planets first near my house and then later wherever I ventured. They have even been dropped from the window I had installed in my plane (um, in remote locations, of course). Soon, I was giving away my little worlds to friends who promised to hide them in their own travels. This eventually became the ‘Infinity Project.’” (Plus, there may still be a Planet on the International Space Station.)

Lloyd Herman, in this excerpt from the catalog essay for the Visionary Journey in Glass exhibit, 2006, stated that, “Hidden on every continent, on the bottom of every ocean, on top of mountains, and in many more remote and mundane places in between, Planets are hidden by participants in the Infinity Project. Marked only with an infinity symbol and no identifying name, Infinity Project Planets are an anonymous thought-provoking gift from Simpson to strangers who may find these little spheres someday, in the next week or the next century.”

Just a Couple More Stories …

– In 1979, Simpson was part of an important exhibition at the Corning Museum of Glass called New Glass. As part of an eclectic group of glass artists, a piece of his work (a goblet) was part of a full-spread image in Life magazine as the opening photo in a story about the exhibit. The show was also headed to the Met Museum, the Louvre, and the Victoria and Albert museum. What a way to step onto the world stage of glass.

– Some of the most successful and artful glass makers inspire Simpson’s work including Lalique, Frederick Carder, Maurice Marinot, and Tiffany. Speaking of Tiffany, “It’s interesting that my grandmother collected his glass. That is probably where I first saw iridescent glass. By the 1950s, Tiffany glass was seen as the most expensive, beautiful glass imaginable. But my grandmother was giving it away to sell at church bazaars.” If only time travel was possible.

– What does Josh Simpson collect? “For a long time, I collected mustard. Because there are so many different interesting mustard jars, from plastic ones that you can squeeze out to French crockery, to glass. One problem arose because it turns out that mustard is acidic. All of the mustard lids that were metal screwtops were ruined. The mustard ate its way out of the cans. I used to have mustard jars all around the kitchen. But it was more of a running joke than anything else.

“I am a pilot, so I collect aircraft items.” I discovered a carburetor from a huge aviation airplane engine under the sink in his bathroom. “I actually have a Pratt and Whitney Double Wasp aircraft engine, which used to be in the garage but we moved it down to the field last summer. It’s about eight feet long and five feet in diameter, has 18 cylinders, and a huge propeller.” I am sure it looks outstanding in his field.

“Every single object that leaves here I have personally made with the help of my hotshop assistants. Sometimes, I work entirely alone. Everything that comes out of here —every single piece that I sign, every piece that leaves this studio—has been made by me, and that’s important. That’s super old school, but it’s important to me.”– Josh Simpson

Related posts: