Nativity Sets Around The World

by Donald-Brian Johnson | Photos by Leslie Piña

“And it came to pass while they were there, the days for her to be delivered were fulfilled. And she bought forth her firstborn son, and wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger, because there was no room for them in the inn.”

– Luke 2: 6, 7

In addition to the expected—angels, shepherds, the Three Kings, and a varied assortment of friendly beasts and villagers—many modern manger scenes also incorporate mythic secular characters. There are little drummer boys, homeless kittens, Elvis shepherds, and kneeling Santas. One of the most lurid current depictions is an outdoor display. Santa, sleigh, and reindeer are shown landing on the stable roof. Stopping by to pay their respects? Just dropping in to fill the stockings? Bethlehem has indeed become crowded, as all join in the celebration of Christ’s birth.

Live from the Earliest of Theaters: Churches

Early pilgrimages to the Holy Land served as inspiration for the Nativity scene tradition, and artists began to offer their interpretations on canvas as early as the fourth century. The Roman basilica of Holy Mary of the Nativity, dedicated in the sixth century, featured the first three-dimensional figures of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, fashioned of wood. The basilica also housed relics reputed to be from the original Bethlehem manger.

It was, however, several centuries more before the concept of a figural Nativity scene really took hold. In the meantime, there were the “living Nativities” or “Nativity dramas” of the Middle Ages, staged in churches by costumed performers as part of seasonal devotions. Known as Mysteres in France, Geistliche Schauspiele in Germany, and Sacre Rappensentazioni in Italy, the earliest and most famous of these was created by St. Francis of Assisi in 1223.

St. Francis felt that, for many of his congregation, Christmas had lost its true meaning. During a personal visit to Christ’s birthplace, Francis was inspired. A “living Nativity” would, he believed, bring his flock closer to the spirit of Christmas. Under his direction, the village of Greccio, near Assisi, was restyled as Bethlehem, with local shepherds (and their livestock) starring as the main characters. On Christmas Eve, torch-bearing villagers arrived in throngs, to experience, in person, the wonder of the crèche.

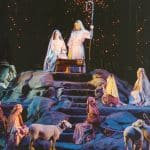

The live Nativity tradition re-surfaced in the mid-twentieth century, and today, many churches stage such seasonal tributes. Congregants, often bundled up under their shepherds’ robes, brave the elements to re-enact the Christmas story in chilly outdoor settings. In the United States, one of the best-known (and most spectacular) modern live re-enactments is the “Living Nativity” at Radio City Music Hall, a New York holiday tradition since the 1930s. Here, the Magi’s camels are the real thing, and a seemingly endless parade of worshipers, (including a full retinue for each King), wends its way toward Bethlehem.

Figural Representation

With live depictions falling out of favor during the Renaissance, the focus was once more on figural representations. These were first popularized in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries by the Jesuits in churches throughout Europe. Whether fashioned of wood, terra cotta, stone, fabric, or metal, each manger scene essentially presented a similar theatrical tableau. The principal Nativity participants were captured at a specific moment in time, paying homage to the Christ Child.

Nativity scenes could be nearly full-size, half-size, or miniature, depending on the available space. The figures were arranged around the manger, often backed by a realistic stable setting. In many churches, tradition held that the figure of the Baby Jesus was not to be placed in the manger until Christmas Eve. (That tradition even served as a plot point for a holiday episode of the 1950s TV detective series, Dragnet.)

By the early seventeenth century, the range of suitable locales for a Nativity set had broadened. Soon, the displays could be found not only in churches but in home environments as well, a custom that had its roots in southern Italy. In some European countries, devout homes even kept a manger scene on display year-round, as an ongoing reminder of Christ’s birth.

Crafted by Hand and by Interpretation

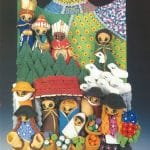

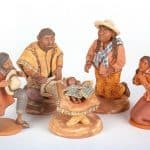

Those who could not afford such splendor, but still wished to celebrate the religious aspects of the holiday, often crafted their own manger scenes from whatever materials were at hand. The resulting creations boast a sincerity better suited to the season’s theme, making the more expensive versions seem gaudy by comparison. As Christianity spread across the globe, this form of handmade self-expression grew and flourished. The influence of individual cultures can be seen to wonderful advantage in Nativity sets from around the world.

Included in this limitless array are carved Nativity gourds from South America. .pine plaques from El Salvador. … clay figurines from Mexico, Peru, and South Africa … terra-cotta ones from Venezuela … Russian nesting dolls, and crèches made of birch bark … Italian blown glass … wood carvings from Ghana, Germany, and Cameroon … limestone and porcelain figures from Ireland … Israeli olive wood renditions … abaca fiber manger scenes from the Philippines … jute and hand-woven cloth representations from Bangladesh … and even an eleven-piece Nativity set from Tanzania, constructed entirely of banana leaves. In Hungary, children observed the tradition known as “betlehemezés,” carrying their handcrafted Nativity scenes from home to home, singing carols and offering prayers.

Each interpretation not only incorporates indigenous materials in its fabrication but also envisions the principal Nativity characters with a sensibility inherent to the locale. A Zulu rendition of the Holy Family, fashioned from fabric, beads, wood, and straw, may seem, on the surface, to have little correlation to European Renaissance paintings on the same theme. There is, however, a strong and poignant bond between the two, representing the universality at the heart of the Christmas story.

In the United States, with the dawn of mass production in the early twentieth century, home Nativity sets came within the range of every household budget. Despite the cookie-cutter sameness in styling, the intentions were good (and no artistic talent was called for). Originally displayed beneath the Christmas tree, by the 1960s crèches had migrated to higher terrain. There they remained safe from the hazards of animated holiday displays, teetering stacks of wrapped presents, and marauding hordes of eager children on Christmas morning.

Today, the theme of the Nativity continues to be re-imagined in countless ways, and with varying degrees of taste. There are Franklin Mint Nativities, many of which hearken back to classic medieval themes … Precious Moments Nativities … Snow Baby Nativities … even a 1999 “Best of Christmas” Nativity with oversized teddy bears donning the robes of the Three Kings. A 2004 “celebrity Nativity” at Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum in London may have stretched the boundaries a bit too far. Among the waxworks costumed as the Holy Family, Wise Men, and shepherds were David and Victoria Beckham, George W. Bush, the Duke of Edinburgh, and Samuel L. Jackson. The Archbishop of Canterbury was “not impressed.” Finding more fans are Nativity scenes like the one displayed each holiday season in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Medieval Sculpture Hall. There, beneath a 20-foot blue spruce (arrayed with 18-century angels), rests the Neapolitan Baroque Crèche with its cast of beloved and familiar characters. Tradition (thankfully) reigns.

For many, however, the only “real” Nativity set is the one that has been handed down in a family, from generation to generation. The plaster may be chipped on this piece, the paint a bit faded on that one. A donkey may be missing a foot, a shepherd the top of his crook, and there may be a Bethlehem Star that stubbornly refuses to light. But still, these visual reminders continue to inspire, just as the Christmas story itself continues to inspire, some two thousand years on. Nativity scenes, in whatever shape, form, style, or skill of execution, celebrate what is for many the pivotal event in the history of the world: the birth of Christ.

“And suddenly, there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host, praising God and saying, ‘Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace among men of good will.’”

– Luke 2: 13, 14

Merry Christmas!

Donald-Brian Johnson and Leslie Piña are the co-authors of numerous Schiffer books on design and collectibles. Dr. Piña is also the co-author of Nativity Crèches of the World. Please address inquiries (or holiday greetings) to donaldbrian@msn.com. Photo Associates: Ramón Piña and Hank Kuhlmann

Related posts: