By Maxine Carter-Lome, publisher

Buffalo Bill Cody, Sitting Bull, Geronimo, Annie Oakley, Rough Riders, Gen. George Custer, Belle Starr, “Wild Bill” Hickok … Most of what we know about these colorful figures of our Western American heritage and their adventures come straight from the embellished and sensationalized stories created for the “Buffalo Bill Wild West” show, a new genre of outdoor entertainment that swept the country starting in the 1880s.

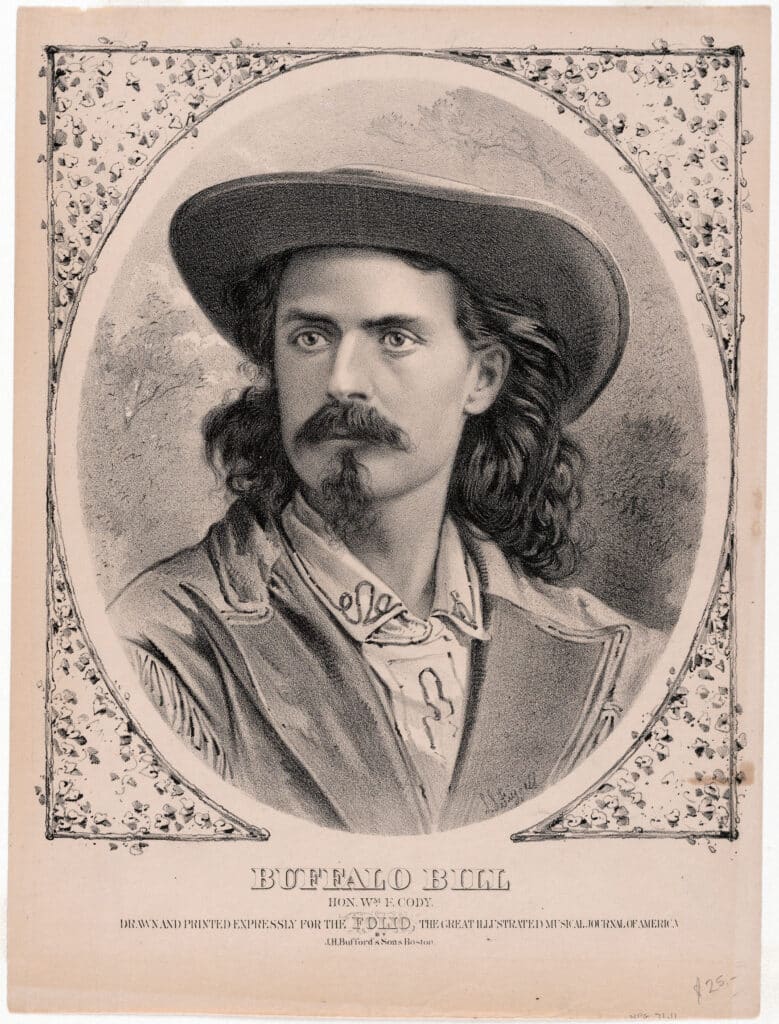

The Rise of “Buffalo Bill” Cody

William Frederick Cody (February 26, 1846 – January 10, 1917) was an American soldier, bison hunter, and showman who claimed to have killed 4,280 buffalo in an eight-month period, thus earning the nickname ”Buffalo Bill.”

Born in LeClaire, Iowa, and raised in Leavenworth, Kansas, Cody left home at the age of 11 to herd cattle and work as a driver on a wagon train. He went on to fur trapping and gold mining and then joined an early version of the Pony Express in 1860.

After the Civil War, Cody scouted for the Army and gained the nickname “Buffalo Bill” for also being a hunter providing meat for the railroad workers. While he was known locally for his endeavors it was not until he met Ned Buntline, a dime novelist who transformed his life into a series of larger-than-life stories, that a then 23-year-old Cody became “Buffalo Bill,” a national celebrity. The first installment of “Buffalo Bill: The King of Border Men” appeared on the front page of the Chicago Tribune on December 15, 1869.

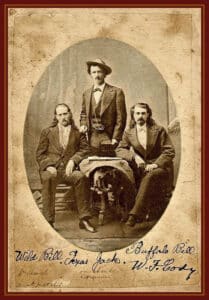

Buffalo Bill’s show business career began on December 17, 1872, in Chicago. He was twenty-six years old. Scouts of the Prairie was a drama created by Buntline, who appeared in it with Cody and another well-known scout, “Texas Jack” Omohundro. The show was a success, with critics making note of Cody’s manner of charming the audience and the realism he brought to his performance. It was obvious by audience response that Buffalo Bill was a showman with something new and exciting to share.

The following season Cody organized his own troupe, the Buffalo Bill Combination. The troupe’s show Scouts of the Plains included Buffalo Bill, Texas Jack, and Cody’s old friend “Wild Bill” Hickok.

Wild Bill and Texas Jack eventually left the show, but Cody continued staging a variety of plays, including ones that were known as “border dramas” (small-scale Wild West shows featuring genuine frontier characters, real Indians, fancy shooting, and sometimes horses if there was space), until 1882, the year Cody conceived of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. It was time for Cody to expand his show from a small stage to an extravaganza the size of a small town.

Preserving the Frontier Life

Cody’s motivation to produce the show was to preserve the Western way of life that he grew up with and loved. Driven by his ambition to keep this way of life from disappearing, he turned his “real life adventure into the first and greatest outdoor western show.”

The first performance of what was then called the “Wild West, Rocky Mountain, and Prairie Exhibition” took place in Omaha, Nebraska the following year. It was an outdoor spectacle with hundreds of performers, as well as live buffalo, elk, cattle, and other animals. This was something new with the ability to both entertain and educate as Cody, the P.T. Barnum of the genre, saw it.

According to Paul Fees, former curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum, Cody used his theater experience to help promote his shows and himself. He was skilled in the use of his fame and credibility as a Westerner to garner fame, publicizing his adventures, colorful and action-packed poster advertising, and lending star appeal with an aura of authenticity to his shows. Most importantly, Cody gave the show a dramatic narrative structure by creating characters and embellishing historical events that made them exciting and memorable. Given his background and reputation, his interpretations of the West as a place of glory and adventure were accepted as genuine and authentic, especially by audiences with no first-hand knowledge.

Taking the Wild West by Storm

generator), Barnsdale brought the show to people who couldn’t get to the city. Selling on eBay for $3,500.

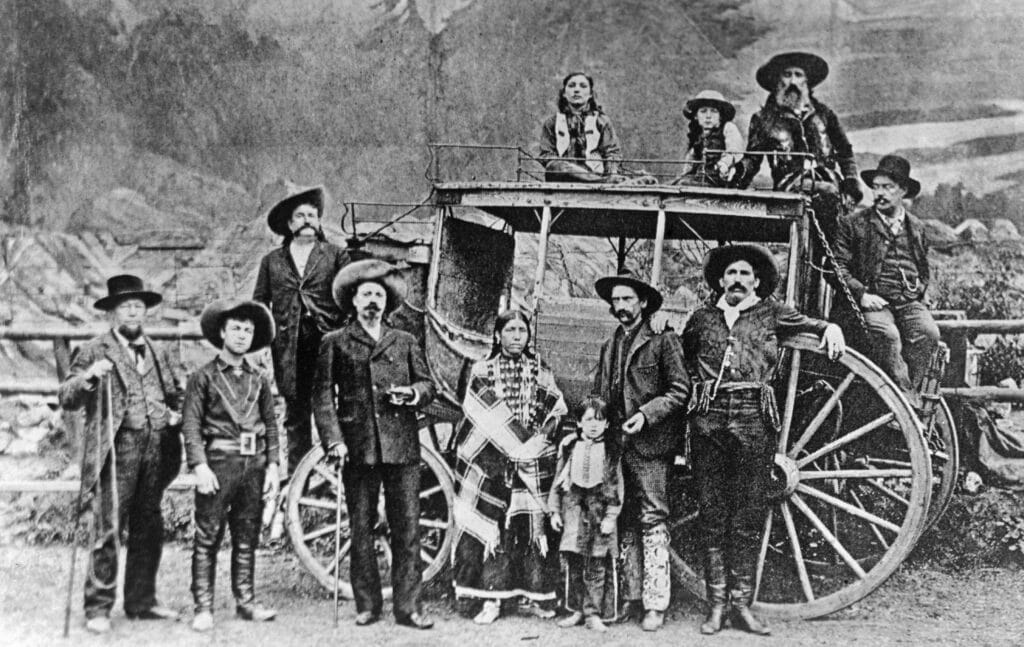

The “Wild West” traveling show promised “genuine illustrations of life on the plains,” with spine-tingling reenactments of buffalo hunts, Pony Express rides, stagecoach attacks, and, in later years, Custer’s Last Stand. Performances also featured scores of cowboys, scouts, buffalo hunters, and Cheyenne, Pawnee, and Lakota men and women dressed in their native costumes and uniforms.

In addition to wild animals, battle re-enactments, equestrian exhibitions, and parades, the Wild West show featured star performers demonstrating such skills as bronco riding, sharp shooting (with pistols and rifles), wing shooting (with a shotgun), roping, and riding. Outlaws, gunslingers, Native Americans, and ex-cavalry riders all found a home in the show, their backgrounds and exploits embellished to create memorable characters and storylines for re-enactments.

“Frontier shows in which real frontier heroes re-enacted their actual deeds were unique to the American theater of the nineteenth century,” wrote Phillip Dray, author of The Fair Chase, The Epic Story of Hunting in America.

“Like the reality TV of our own time, the shows appealed largely to low- or middle-brow audiences that enjoyed the frisson of seeing authentic pugilists, politicians, feathered warriors, or border men such as Cody and (Wild Bill) Hickok perform, for the most part awkwardly, as themselves. The payoff was the chance to see dramatizations of real-world events portrayed by the non-actors who had in fact carried them out, who wore the same clothes, spoke the actual names of the Indians and criminals they’d killed, and, often used as stage props, the genuine guns, knives, hatchets, or other implements involved.”

Traveling with a show the size of Wild West—both in the United States and Europe—was a logistical nightmare and a huge expense. By the late 1890s, the show carried as many as five hundred cast and staff members, including twenty-five cowboys, a dozen cowgirls, and one hundred Indian men, women, and children, all needing to be fed three hot meals a day. Performers lived in wall tents during long stands or slept in railroad sleeping cars when the show moved daily. Besides performers and staff, hundreds of show and draft horses—and as many as thirty buffalo—needed to be transported. The show also carried grandstand seating for twenty thousand spectators along with the acres of canvas necessary to cover them. Expenses ran as high as $4,000 per day! Yet the public demand kept Cody’s Wild West show on the road through the first decade of the 20th century and made Cody one of the wealthiest and most famous entertainers in the world.

Places of Interest

In 1887, the Wild West was invited to England to participate in the American Exhibition, the same year as Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee celebration. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was a hit, visited by nobility, commoners, and Queen Victoria herself. The show was credited with improving British and American relations. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West rose to international fame and returned two years later to tour the European continent.

The Wild West also played at the 1893 Columbia Exposition in Chicago to great acclaim. On a city block adjacent to the fair, Cody staged the latest incarnation of his show, billed by that point as “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World.” There were “450 horses of all countries,” trumpeted across the ads, flyers, and posters.

It was called “the greatest equestrian exhibition of the century,” gushed the Chicago Tribune. “In addition to Indians, cowboys, Mexicans, Cossacks, Arabs, and Tartars are detachments from the Sixth United States Cavalry, French chasseurs, German Pottsdammer reds, and English lancers. These representatives of trained mounted soldiery are fully as hardy as the barbarous riders, and many of the feats they performed were quite as wonderful.”

From April 26 to October 31—a longer run than the Columbian Exposition itself by one day—Cody and his company performed before packed grandstands. Despite the marvels of the White City, visitors couldn’t claim to have seen the fair if they didn’t also attend the “Wild West.” Cody personally made sure everyone had the opportunity to attend: On July 27, he treated 6,000 poor children to a downtown parade, a picnic, all the ice cream they could eat, and a visit to the Western spectacle at Stony Island Avenue and 63rd Street, reported the Tribune.

The Decline of the Wild West

In the 1890s, according to Fees, Wild West began to add sideshows and other circus elements in an effort to bolster ticket sales. “If the West seemed too familiar, ‘Far East’ acts such as Arabian acrobats or dancing elephants and thrill acts such as bicyclists and high divers might inject sufficient novelty to draw new spectators.” New performances dramatizing such historical epics as the Charge at San Juan Hill and the creation of the Congress of Rough Riders of the World were also added to the program; however, despite Cody’s best efforts to keep the show fresh and exciting, ticket sales declined in the first decade of the 20th century as the publics’ interests changed and Europe and America braced for war.

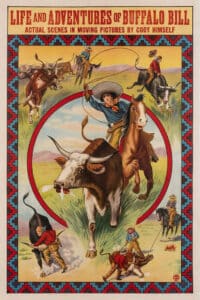

According to Fees, Americans’ interest in the Wild West could now be experienced in other ways and venues. “Motion pictures captivated public attention – the West could seem more real on the screen than in the arena. Shooting declined as a spectator sport while the popularity of sports including baseball and football soared. Riding and roping could be better showcased in rodeos, which were considerably less expensive to produce than Wild West shows. The old western stars were fading as well—even Buffalo Bill seemed like a relic—and Indian people appeared to be quietly confined to reservations. The “old West” was no longer so exotic nor, at the same time, so relevant to a world of heavy industry and mechanized warfare.”

In 1913, Buffalo Bill borrowed money from Denver businessman Harry Tammen to keep his show afloat, not realizing the loan would be used to force him to appear in Tammen’s Sells Floto Circus. Cody fell behind in payment of the loan and when the Wild West stopped in Denver to do a show that July, Tammen had the show seized. The Wild West was sold off at auction in Denver’s Overland Park and Cody was forced to join the Sells Floto Circus.

Eventually, he got out of that contract but was never able to rebuild his Wild West. By 1920, the stories, stars, and characters that defined the Wild West show had moved on to appear on film in Western movies.

Related posts: