By Lina Mann, Historian, The White House Historical Association

“I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves.”

– First Lady Michelle Obama, 2016

When First Lady Michelle Obama delivered this powerful statement during a speech before the Democratic National Convention on July 25, 2016, she shed light on a less-discussed element of White House history. Enslaved people were involved in every aspect of White House construction – from the quarrying of stone to the cutting of timber, to the production of bricks, to the physical labor of assembling its roof and walls. Enslaved people worked as axemen, stone cutters, carpenters, brick makers, sawyers, and laborers throughout each stage of construction from 1792 through 1800. As Mrs. Obama highlighted, the use of enslaved labor to build one of the most revered symbols of American democracy, and the home of the President of the United States, represents the paradoxical relationship between the institution of slavery and the ideals of freedom and liberty enshrined in America’s founding documents.

While many authors and historians have dedicated scholarship and research to the construction of the White House, this article builds upon their efforts by weaving in the stories of the enslaved people who often were excluded entirely from this narrative.

The Beginning

The building site of the President’s House in the 1790s included a great house of brick and stone rising in the middle of a hive of free and enslaved workmen. Quarrymen, sawyers, brick makers, and carpenters fashioned raw materials into the elements of the vast structure. The exterior of the residence looked finished by 1800, but it would take two more years to complete the interior’s monumental architectural details. – “Building the President’s House,” The White House Historical Association

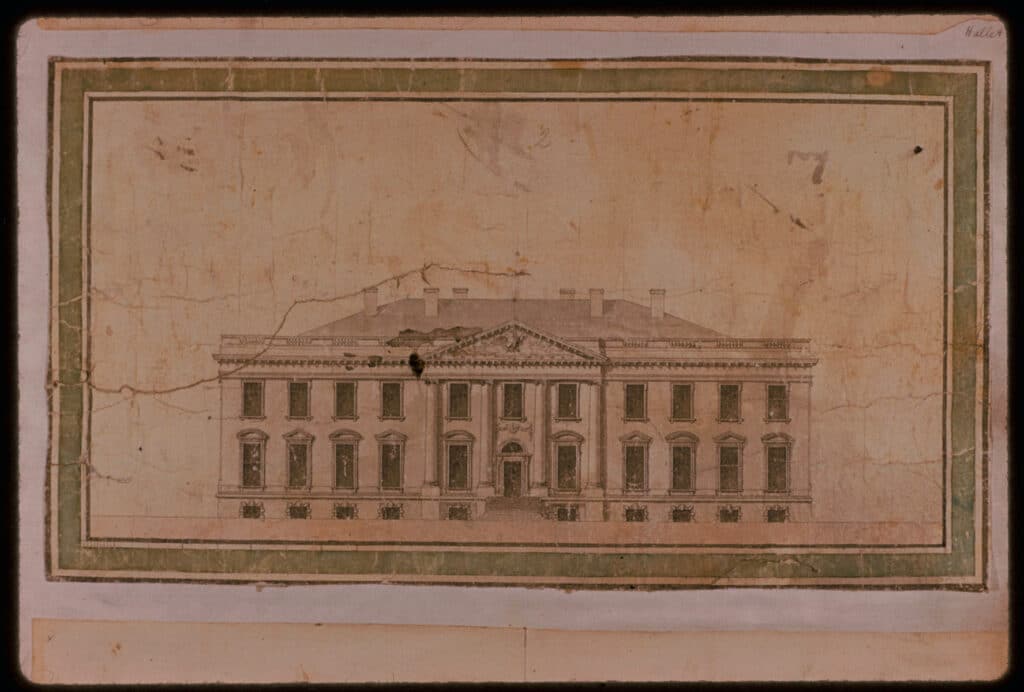

After Congress passed the Residence Act on July 16, 1790, establishing the location for the new capital city of Washington, D.C. along with the banks of the “river Patomack,” President George Washington took an active role in overseeing the construction in Federal City. He appointed three commissioners for the District of Columbia in January 1791 to manage federal construction projects: Thomas Johnson, David Stuart, and Daniel Carroll. Soon after selecting the commissioners, President Washington appointed French-born engineer Pierre (Peter) Charles L’Enfant to survey, map, and plan the new city. Together, they selected the site for the White House. The following year, in March 1792, the commissioners announced and advertised a national design competition for the President’s House and Capitol Building. In July, Irish-born architect James Hoban’s design for the President’s House was selected by the commissioners with Washington’s approval, and preparations on the building site commenced. On October 13, 1792, White House construction officially began with the laying of a cornerstone during a Masonic ceremony.

Over the course of the next eight years, enslaved laborers worked alongside white wage workers and craftsmen to produce raw materials and construct the President’s House. First, laborers cleared the land, built roads, wharves, and bridges, and felled trees to make way for construction. In December 1791, the federal government purchased a stone quarry belonging to the prominent Brent family on Wiggington’s Island in Stafford County, Virginia. Situated on a small tributary called Aquia Creek, several miles inland from the Potomac River, the quarry provided easy transportation of stone upriver to the building sites of the President’s House and Capitol Building. While the labor records for the quarry’s operation are incomplete, the records of the commissioners and their published advertisements suggest that enslaved people were later hired to cut and move this stone. Meanwhile, brick masters built kilns near the White House building site to produce bricks for the building’s interior structure, while axemen felled trees in Maryland and Virginia forests and shipped the lumber to Washington to be used as floor and roof timbers.

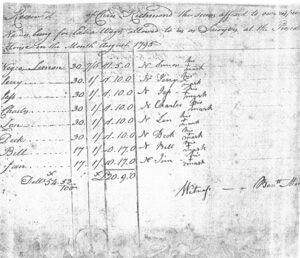

As building materials were produced and gathered, laborers constructed the building under the watchful eye of foremen and overseers. Throughout the construction, most unskilled laborers earned around $0.31 per day. Skilled craftsmen like stone cutters earned closer to $1.34 per day. While there were certainly some skilled enslaved laborers, most were probably considered unskilled and their owners were paid as such. Although the White House was not entirely complete, most construction had concluded when President John Adams moved into the residence on November 1, 1800.

The Labor

The decision to use enslaved labor in construction came naturally to the commissioners. All three of the original commissioners belonged to the landed gentry and owned enslaved people. Some of the later commissioners belonged to the landed gentry and owned enslaved people. Some of the later commissioners even hired out their own enslaved people to labor on the Capitol Building and the White House. For Example, Gustavus Scott, who began serving in the role of commissioner in 1794, hired out two enslaved men named Bob and Kit, pocketing their wages for himself. In addition, the location of the new Federal City carved out of two states that permitted slavery, Maryland and Virginia, made it convenient to hire out enslaved individuals from nearby landowners.

The use of enslaved labor to build one of the most revered symbols of American democracy, and the home of the President of the United States, represents the paradoxical relationship between the institution of slavery and the ideals of freedom and liberty enshrined in America’s founding documents. – Author Lina Mann

The first mention of slavery in the commissioners’ records appeared on April 13, 1792, when they resolved to hire, “good labouring negroes by the year, the masters cloathing them well and finding each a blanket, the commissioners finding them provisions and paying twenty one pounds a year.” This course of action was not a new one, as many local slave owners had been hiring out their enslaved laborers to neighbors and businesses for some time. Owners collected the wage while continuing to provide clothing and some medical care. The commissioners typically provided workers with housing, two meals per day, and basic medical care. This arrangement allowed the nascent capital to reap the benefits of labor without bearing total responsibility for the workers’ general wellbeing. If an enslaved worker did not show up to work, the overseer simply docked the pay given to the owner.

Many of the documented enslaved laborers worked on both the White House and the Capitol Building. Because these two projects were so closely intertwined, it is often difficult to determine which laborers specifically worked on the White House between the procurement and production of resources and the shuttling of labor between sites.

According to meticulous research by historian Bob Arnebeck, over 200 known enslaved individuals labored on the White House and Capitol Building. You can access an index of the enslaved people currently identified at www.whitehousehistory.org/index-of-enslaved-individuals. However, there are likely many more enslaved people who worked on these federal building projects and remain unknown – their names are either lost to history or await future discovery.

Case in Point: George Fenwick

Determining anything more than an enslaved person’s first name is extraordinarily difficult. Their names are often denoted as the enslaved individual’s first name, their owner’s full or last name, and their owner’s signature on payrolls and timesheets from 1794 to 1800. One such timesheet contains the name “N Jacob George Fenwick.” The “N” in front of the name indicates that the worker was enslaved. Jacob was his first name and George Fenwick was his owner. With only a first name, it is difficult to learn more information about Jacob. However, some details can be extracted from just a name, such as a location and genealogical information about the slave owner. According to additional records, it appears George Fenwick also hired out another enslaved man—Orston—for federal construction projects. By using available genealogical information about Fenwick, it can be determined that he was born sometime before 1749 in St. Mary’s County, Maryland. He died in Washington, D.C. on October 26, 1811. According to the 1800 census, the year White House construction concluded, Fenwick lived with three enslaved individuals at his Georgetown home. Based on this information, it might appear that Fenwick did not own many enslaved individuals. His 1811 will, however, paints a different picture.

According to the will, George Fenwick left four city lots in the new city of Washington and significant tracts of land in Prince George’s County, Maryland, and St. Mary’s County, Maryland, to his sons. He also left his wife, Margaret, “my dwelling plantation in St. Mary’s Co., called ‘Swamp Island’ and lots before mentioned; also half of all my negroes.” The direction to leave his wife “half” of his enslaved people suggests that he owned a considerable number of enslaved individuals. In addition, Fenwick stated that his land in Prince George’s County contained 287 acres, while his St. Mary’s County plantation consisted of 400 acres. The amount of acreage listed in this will suggests that Fenwick was involved in tobacco farming, one of the most lucrative crops in southern Maryland for the time period.

The intensive nature of this crop typically required large amounts of enslaved labor to cultivate and harvest. Therefore, this information suggests that Fenwick was likely a wealthy plantation owner. The Jacob and Ortson listed in the commissioners’ records probably came from one of these locations in southern Maryland.

Going Local

Many slave owners who appear in the surviving [construction] documentation came from southern Maryland, specifically Prince George’s, Charles, St. Mary’s, and Calvert Counties. Each of these counties had convenient access to the Potomac River, making it easy to transport enslaved people upriver to work on federal construction projects like the White House. Some slave owners in northern Virginia also supplied enslaved labor to Washington, D.C. Because the capital city did not have a large population at the onset of the initial construction, the

commissioners hired out enslaved people from a variety of slave owners in Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. Since the commissioners were wealthy landowners themselves, it is likely they communicated with other landowners to create a network of enslaved labor.

While available genealogical information reveals more about the slave owner than the enslaved workers, sometimes it is possible to glean additional pieces of information about the lives of the enslaved. This is currently the case with the Brent sisters: Eleanor, Elizabeth, Mary, Jane, and Teresa. These women each appear in records related to the commissioners’ proceedings. A receipt dated July 7, 1796, from a cobbler named Delphey lists each of the Brent sisters and the shoes made for their enslaved people. According to this receipt, Eleanor fitted Charles and David; Elizabeth fitted Gabe and Henry; Jane fitted Silvester; and Teresa fitted Nace for new shoes. This receipt provides an example of the terms of the short-term contract agreements for the enslaved. While the commissioners were responsible for providing payment to slave owners like the Brent sisters for the labor of their enslaved people, the slave owners were responsible for providing the clothing. The example of the Brent sisters shows how slave owners fulfilled the clothing obligation of their contract with the commissioners. Most enslaved people working on federal building projects probably did not have many items of clothing. Receiving a new pair of shoes during construction must have been incredibly valuable.

According to surviving documentation, at least nine presidents either brought with them or hired out enslaved individuals to work at the White House: Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, John Tyler, James K. Polk, and Zachary Taylor. – FAQs, the White House

Historical Association

Architect James Hoban

White House architect James Hoban also hired out his enslaved workers. Payrolls listing carpenters working on the President’s House from 1794 to 1797 list four enslaved individuals belonging to Hames Hoban: Ben, Daniel, Harry, and Peter. This record is one of the few instances of enslaved people working as craftsmen. Ben, Daniel, and Harry each made the same wage as white adolescents apprenticed to the carpenters while Peter earned a “shilling or two” less than the free white carpenters. While the arrangement was unusual, since Hoban held significant influence, the commissioners likely let him employ the people he wanted on the project. Later, in November 1797, the commissioners ordered “that after the expiration of the present month no Negro Carpenters or apprentices be hired at either of the public buildings.” By this point funds were tight, Hoban’s enslaved carpenters were making a similar wage to the white apprentice carpenters. At any rate, Hoban did not protest the order.

During the final days of White House construction, labor forces—both enslaved and free—were drastically cut by the commissioners. By this point, the exterior was largely finished, and free white carpenters furiously worked to finish the interiors. The final known receipt for payment to a slave owner occurred on June 7, 1800, when the commissioners paid $19.74 to a slave owner named Joseph Queen for the use of enslaved sawyers. Although major White House construction concluded around the time President John Adams moved into the home, enslaved labor was used again for the rebuild after the British burned the White House on August 24, 1814.

Additional research into the lives of the enslaved individuals that built and rebuilt the White House is ongoing, as historians hope to learn more about the identities and life experiences of known and unknown enslaved people. If you have any additional information about any of the enslaved individuals listed here or any other enslaved people associated with White House construction, please reach out to the White House Historical Association’s Slavery in the President’s Neighborhood initiative at SPN@whha.org

This article was originally published by the White House Historical Association on January 3, 2020. It is reprinted here with permission. Visit www.whitehousehistory.org

Edited by Judy Gonyeau, managing editor, Journal of Antiques and Collectibles

Related posts: