by Maxine Carter-Lome

“There isn’t an artist painting today, in the science fiction fantasy field,

who didn’t start with Chesley Bonestell” – Ray Bradbury

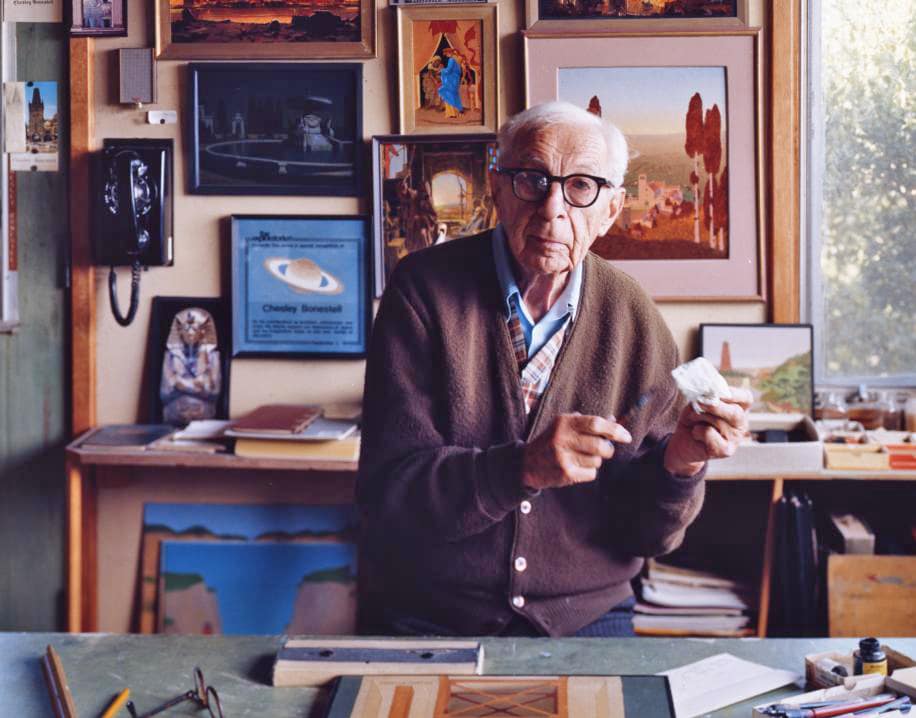

What do the Chrysler Building, the Golden Gate Bridge, the film Destination Moon, and America’s space program all have in common? They were each touched by the creative vision of a forgotten artist named Chesley Bonestell (1888-1986). It can be said that Bonestell, an American pioneer of space art, helped get us to the moon – not with technology, but with a paintbrush.

Space: A Fascinating Frontier

Bonestell is well known among hardcore science fiction fans for his cover art for such magazines of the 1950s-70s as Astounding Science Fiction and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, as well as his collaboration with several well-known authors in the field of space exploration on such books as The Conquest of Space, The Exploration of Mars, and Beyond the Solar System.

Bonestell’s astronomical adventures were launched in 1905 after seeing Saturn through the 12-inch (300 mm) telescope at San Jose’s Lick Observatory and then painting what he had seen. Although the painting was destroyed in a fire in the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake, the imagery and his interest in Astronomy stayed with Bonestell even while he was forced to shift gears and earn a living for his family as an architect.After taking evening classes at the Hopkins Art Institute and then dropping out of Columbia in 1907 as an architectural major, Bonestell went on to build a career and reputation as a renderer and designer for several of the leading architectural firms of the time, working on such important projects as the Chrysler Building (the gargoyles at the top were a Bonestell touch), the U.S. Supreme Court Building, the New York Central Building (now known as the Helmsley Building), and several state capitols.

Back Down to Earth

When the Depression hit, Bonestell moved his family back to California and was hired by Joseph Strauss to illustrate the designs of the Golden Gate Bridge. Bonestell’s beautiful renderings delighted both the city fathers and the public and is credited with helping the bridge get built. From there, Bonestell traveled to Hollywood to pursue a career in motion pictures, where he quickly established himself as one of the film industry’s premiere matte painters. He painted the massive cathedral featured in the 1939 version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, worked closely with Orson Welles on Citizen Kane, for which he painted Xanadu, Kane’s palatial estate, and was also involved in the design of Filoli, the huge California estate featured in the TV series Dynasty.

To Infinity & Beyond

It was Bonestell’s association with Hollywood animator and producer George Pal that ultimately brought him to the attention of science fiction fans. Pal was aware of Bonestell’s talent as an astronomical painter and hired the artist to create realistic planetscapes and other pieces for such popular Pal-produced ‘50s shows as Destination Moon, When Worlds Collide, The War of the Worlds, and Conquest of Space.

In 1944, Life magazine published a series of paintings by Bonestell depicting Saturn as seen from its various moons. The paintings provided inspiration for what worlds beyond our own might look like. His painting Saturn as Seen from Titan is perhaps the most famous astronomical landscape ever and is nicknamed “the painting that launched a thousand careers” for the generation of scientists inspired to explore the cosmos by his astonishingly accurate representations. “He was creating planetary sorts of images prior to us even walking on the moon,” said Tonya M. Cribb, museum director at the Plattsburgh State Art Museum, which held an exhibit earlier this year entitled The Father of Space Art: Chesley Knight Bonestell.

Lunar Rebirth

One of Bonestell’s most public and perhaps largest art installations was his painting of the Moon for The Museum of Science in Boston’s Charles Hayden Planetarium, unveiled in 1957. A Lunar Landscape was an enormous ten-by-forty-foot mural designed to give museum visitors the experience of what they might see if they were astronauts exploring the Moon. A year after the Apollo 11 Moon landing, however, the Museum of Science decided that A Lunar Landscape had to come down due to the artwork’s now-documented inaccuracies. In 1976, it was sent to the Smithsonian and put into storage and not deemed worthy of restoration; however, after over 50 years out of public view, this iconic piece of artwork will go back on public display at the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum’s new Destination Moon exhibit as part of its museum-wide renovation program.

In this new age of space travel, Bonestell’s work and the inspiration it inspires is being re-introduced to a new generation of science fiction fans and fans of space and space art with the 2018 award-winning documentary on his life and work titled Chesley Bonestell: A Brush With The Future. NASA is honoring him, as well. Through a special opportunity made available to the public by NASA, Chesley Bonestell was an “electronic passenger” aboard Artemis 1 and the Mars Perseverance Rover with his own commemorative boarding passes and is now floating above Earth on the International Space Station with a birds-eye view of the vastness of his imagination.

Related posts: