by Maxine Carter-Lome, publisher

“The Boston Advertiser prints an interesting account of an experiment in carrying out a conversation by word of mouth over a telegraph wire, made by Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Watson. … In a distance of two miles, with Mr. Bell in Boston and Mr. Watson in Cambridge, conversation was carried on for about half an hour, generally in an ordinary tone of voice, but often in whispers. The credit for this important discovery is due to Mr. Bell.”

– Arizona Citizen, November 18, 1876

The 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, was the first World Fair held in America. The 10 million-plus people who attended the May 10th to November 10th manufacturing trade show witnessed a wide range of newfangled products that included everything from bananas to telephones. Among the visitors and exhibitors that year were George Eastman (Kodak), George Westinghouse, a young Thomas Edison with his electric pen and automatic telegraph system, and a very reluctant Alexander Graham Bell, whose contraption, above all others, ended up as the talk of the fair.

Bell had no interest in going to the fair and showing off his invention. Besides, it was a busy time at the university in Boston where he was teaching and he had student tests to grade. Perhaps he was nervous or afraid that if his invention did not work properly, he would be embarrassed.

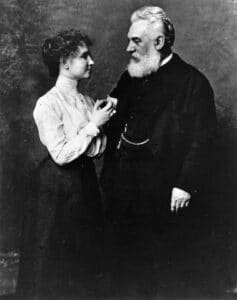

Bell’s fiancée Mabel Hubbard and her father, Gardiner Hubbard, tried to persuade him otherwise. It was, they pointed out, a chance of a lifetime to showcase his invention in front of newspaper reporters and scientists from all over the world. Judges would present awards to the best and most promising inventions. Bell held his ground. Mabel took matters into her own hands.

On June 24, Mabel surprised Bell with an afternoon carriage ride to get him away from the university for a few hours. For Bell, it was a chance to briefly leave the pressures of work behind. What he did not know was that Mabel had arranged for the carriage driver to take them to the train station. She had secretly bought Bell a round-trip ticket to Philadelphia, and she and her mother had packed him a bag the night before that was in the carriage with them.

Recognizing he had been tricked, Bell refused to board the train until Mabel threatened to call off their engagement. Reluctantly he got on the train, believing the trip was a waste of his time.

Bell gave the first public demonstration of his instrument on a sweltering afternoon in June in front of an audience that included Emperor Pedro of Brazil and Lord Kelvin standing 20 feet away from Bell when he picked up the transmitter and spoke into his machine. When Pedro put the receiver to his ear, he uttered his now-famous words, “My God, it talks!” Lord Kelvin took the receiver and reportedly said, “It is the most wonderful thing I have seen in America!”

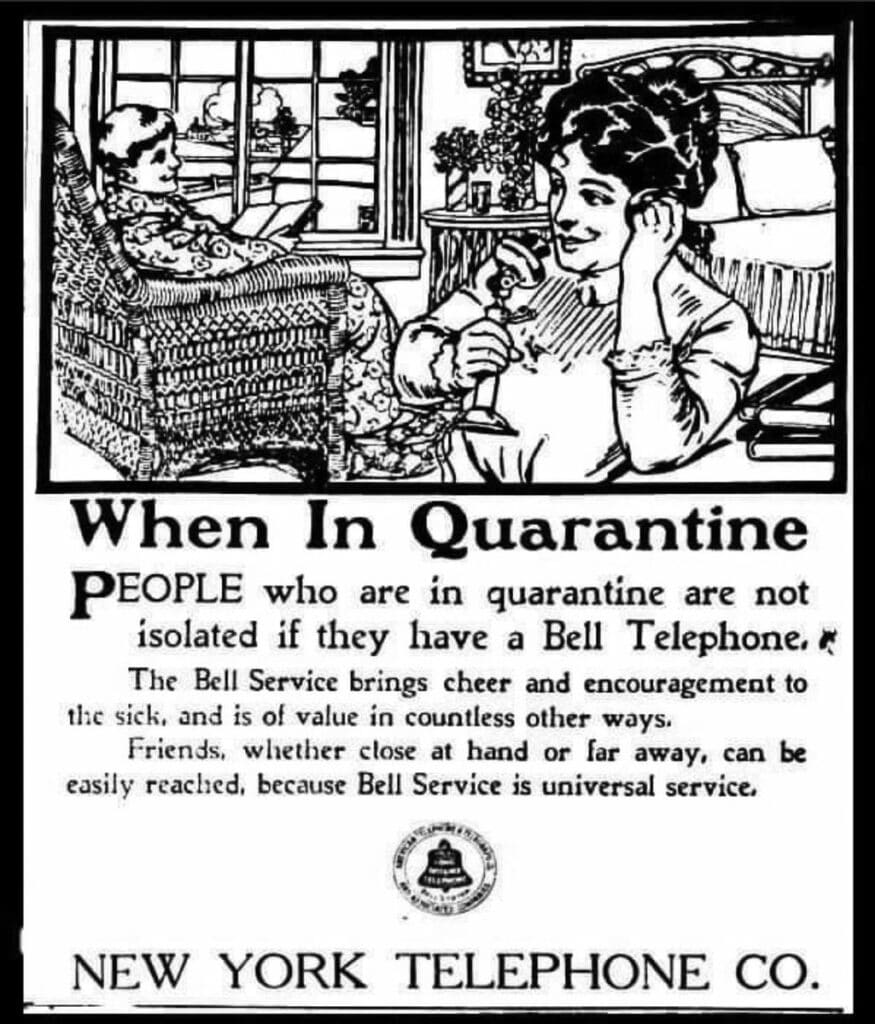

From that day on everything changed for Bell. The public was enthralled by the technology’s possibilities. By 1900 there were nearly 600,000 phones in Bell’s telephone system; that number shot up to 2.2 million phones by 1905, and 5.8 million by 1910.

Studying Speech and Sound

Mabel Hubbard Bell (1857-1923). She suffered a near-fatal bout of scarlet fever close to her fifth birthday in 1862 while visiting her maternal grandparents in New York City, and was thereafter left permanently and completely deaf. She and her father were significant supporters of Bell and his inventions.

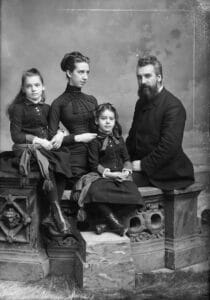

Alexander Bell was born in 1847 in Edinburgh, Scotland, and was home schooled until age 11 by his mother, Eliza, who was hearing impaired. She could only hear by using a rubber ear tube. People who wanted to speak to her spoke directly into the ear tube.

Bell’s father, Alexander M. Bell, was a professor of speech elocution at the University of Edinburgh, and well-known as a teacher for children with hearing and speech problems. Aleck, as he was called then, grew up watching his father research the mechanics of speech, exploring how people spoke and what parts of the mouth made certain sounds. Perhaps his father’s work and his mother’s own challenges are what led a teenage Alexander to apply his curiosity and love of science to his own inventions and explorations, including the discovery of how speech could be transmitted electrically, and developing a machine that could reproduce human speech.

At 23, Bell started experimenting with converting music into an electrical signal. By age 26, now living in the US, he was exploring ways to transmit the human voice over wire in much the same was as the electrical telegraph. Invented 40 years earlier, the telegraph would transmit ‘clicks’ to communicate messages over a great distance. Bell had found that human speech came in wave-like patterns. He now hoped to produce an electrical wave that would follow the same patterns as someone’s speech.

Bell won financial backing from Gardiner Hubbard (who would become Bell’s father-in-law) and Thomas Sanders, two wealthy investors. Hubbard also brought in Anthony Pollok, his patent attorney. The money enabled Bell to hire Thomas Watson, a skilled electrical engineer whose knowledge complemented Bell’s. To this day, Watson is intertwined in the historical retelling of Bell’s important invention.

The Patent Wars

The following year, in 1875, Bell and his investors decided the time had come to protect his intellectual property using patents. They filed first in the UK and then in the US in 1876. However, Elisha Gray had already beat Bell to the U.S. patent office in February 1876 for a telephone which used a variable resistor based on a liquid: saltwater. Bell’s patent was for a liquid mercury-based variable resistor.

With his patent filed and his concept protected, Bell turned to the final steps necessary to make his telephone work. He and Watson finally accomplished the task three days later with the now-infamous message—“Mr. Watson, come here, I need you”—from Bell to his assistant. As this working telephone was based on a design similar to Gray’s, Gray lay claim to having invented the telephone while Bell reaped the glory.

On the heels of Bell’s success at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, the Bell Telephone Company was organized in 1877. He and Mable Hubbard married and embarked on a tour of Europe to demonstrate the telephone. Upon their return to the United States, Bell was summoned to Washington D.C. to defend his telephone patent from lawsuits. Others, like Gray, claimed they had invented the telephone or had conceived of the idea before Bell. Over the next 18 years, the Bell Company faced over 550 court challenges, including several that went to the Supreme Court, but none were successful.

Bell is credited with the now famous saying “when one door closes another door opens.” By 1880 Bell began to turn business matters over to Hubbard and others so he could pursue a wide range of other inventions and intellectual pursuits, for which he held 18 patents in his name alone and shared another 12 with collaborators. Among his lesser-known inventions are the Photophone, a telecommunications device that allows transmission of speech on a beam of light; the Hydrofoil, a lifting surface or “foil” that operates in water; HD-4, an early research hydrofoil watercraft; the Audiometer, a device used to evaluate the hearing threshold of a person; and the Metal Detector, an electronic instrument that detects the presence of metal nearby.

Bell died peacefully on August 2, 1922, at his home in Baddeck on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. Shortly after his death, the entire telephone system was shut down for one minute to pay tribute to his genius.

Collectibles Market

Like many inventions, time improves on everything from design and size to performance, which has certainly been the case with the telephone, which makes this such a popular and universally-relatable collectible category. Who among us over a certain age does not remember the telephone attached to the wall and limited by the distance of a cord? Or rotary dial telephones? Or, the princess telephones of the 1960s that came in colors and featured light-up dials? And character-designed, novelty phones like Mickey Mouse or Snoopy? With over 140 years of commercial products on the market, there are lots of samples to collect, and ways to build a collection.

Initially, phones were rented by the homeowner through their local telephone company, to whom they paid a monthly fee. You could not outright buy the telephone device and options were limited to the “Ma Bell” phones they sold. What was then a monopoly owned by AT&T changed in 1983 when the U.S. government ended AT&T’s monopoly and consumers suddenly had the option to buy their own phone. New phone manufacturers entered the market to provide a variety of options to suit any decor. The phone market exploded!

What’s It Worth?

With so much product history is everything old worth anything? Collectible phones come in many forms. Wall mount, push-button, candlestick phones, desk sets, decorator, and novelty phones are all collectible. Some are of modest value while others can fetch hundreds in the right setting.

Wooden wall mount phones first appeared in the late 1870s. Expensive to own and tricky to operate, you reached your party through the use of an operator or by a series of short and long cranks of a handle, not unlike sending Morse Code. These phones hit their peak of popularity as a collectible in the mid-1990s and have since dramatically decreased in value. The most common models were made by Western Electric in 1919 and in the current market can often be found in the $80 to $100 range with phones from historic buildings fetching a premium for their history.

Vintage rotary phones, in general, have been gaining value as they become harder to find, and their designs and colors connect with the retro decorating vibe. For a vintage rotary phone in mint working condition, prices typically range from $20 to as high as $500 for rarer phones, although on average you can find these phones in the $40 to $70 range.

With their slender and elegant design, early candlestick phones, produced from the 1890s through the 1920s, are also in great demand, especially the earliest turn of the century nickel-plated models which can be difficult to find and quite pricey. Also referred to as an “upright,” these phones were manufactured in limited numbers as a luxury item. Later models, from 1920 to 1940, were mass-produced and are a more common and more affordable find.

Color was first introduced in 1954 with the original colors being ivory, dark green, green, dark gray, red, brown-beige, yellow, and blue. Gray, blue, brown, and beige were discontinued in 1957. In 1964, pink, light gray, and turquoise were added to the color lineup. Pre-1955 colored phones will have a metal finger wheel; with newer models, the wheel will be plastic. Currently, phones from this era are bringing $30 to $80.

While Western Electric is the big name for many American collectors, makers like Automatic Electric, Kellogg Switchboard and Supply, Stromberg Carlson, and others are also in high demand. Many telephone collectors also focus on related items such as telephone signs and switchboards.

With landline phone sales in steep decline today as more consumers update their phone service with cellphones and smartphones, these phones keep us connected to our past, and the legacy of Alexander Graham Bell.

Related posts: