The Vanity Table, Then and Now

by Erica Lome

Almost every home has a space for “putting on one’s face.” Perhaps without our conscious knowledge, dressing tables have made this a normal and routine part of our day. Like many ubiquitous furnishings, we often don’t realize how much they shape our habits. Tracing the history of the vanity table takes us from the opulent palaces of Europe to the refined townhouses of Victorian America, and finally to our own bedrooms.

Intrinsically tied together with the vanity table is the toilette, or the tradition of personal grooming stretching back to the middle ages. Women would mark the transition of a household table into a space for use of dressing or applying cosmetics with the addition of a toile, or cloth. Modifications and refinement to the toile continued through the Italian and Northern Renaissance, as the demand strengthened for more personalized furniture to display cosmetics or wigs, and store them when not in use.

In visual culture, the dressing table symbolized both positive and negative aspects of the rich and entitled. They also demonstrated the high cost of vanity, as the art of dressing up took on more and more detailed machinations. It was a common subject of satire, poking fun at the lengths people would go to look their best (and richest). This was not solely restricted to women – by the late eighteenth century, men too were avid consumers of grooming and beauty products, adorning themselves in the latest fashions. The foppish, extravagant, and self-obsessed character of the dandy originated during this period to embody the habits of young men who spent ages in front of a mirror getting ready. Particularly as shaving became a popular habit, some dressing tables adapted to the posture of male users, standing on higher legs with more of a box-like shape and a detached mirror.

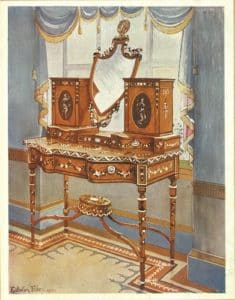

Across the ocean, vanity tables were a staple of refined colonial American households. Designs for these forms were predominantly disseminated from French and English sources, with cabinetmakers such as Chippendale, Sheraton, and Hepplewhite publishing catalogs and exporting them to shops in New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. Imitations by American craftsmen show how influential this transatlantic network was: even after the nation declared independence, it was still considered the height of taste to own or emulate British furniture.

By the mid-nineteenth century, singularly-commissioned vanity tables gave way to industrialized manufacture. Correspondingly, pieces like dressing tables were made quicker and more cheaply, reaching an entirely new audience of consumers. For Americans seeking to look respectable amongst their peers, decorating one’s home with elite-looking objects signaled both a disposable income and the leisure time to adorn oneself according to the latest fashions. Tips on household management and furnishings advocated that the home should be a refined and moral space, free from the polluting influences of the outside world. A house in good taste, with the requisite objects, evidenced the goodliness of its occupants.

A sample from The Ladies’ and Gentleman’s Etiquette: A Complete Manual of the Manners and Dress of American Society by Eliza Bisbee Duffey in 1874 outlines the myriad of accessories required specifically for the vanity table:

Most middle class homes often did not have separate spaces for dressing, and the vanity table moved into the bedroom, considered the most private space. Such households did not employ servants either, leaving women to attend to themselves. No longer free to take up as much space, vanity tables became compact and designed to coordinate with other bedroom furniture. Of course, the lavish wealth of the Gilded Age told a different story, and extravagant dressing tables were made for the boudoirs of the nation’s elite families.

The advent of the twentieth century led to innovations for the vanity table, both in design and social meaning. At the higher end of the spectrum, the European “moderne” style, debuting at the 1925 Paris “Exposition des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes” challenged mass-produced and industrially-made furniture by incorporating naturalistic ornamentation, handcrafted techniques, and an ideology of design linked to the user’s personality. Art Nouveau and Art Deco furniture makers saw the dressing table as a canvas for experimenting with style and form.

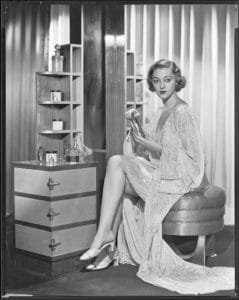

Yet for most Americans, the vanity table became irrepressibly linked to femininity and changing standards for gender in society. Women were more visible in the public sphere, with new opportunities for work and wage-earning challenging the status-quo. Increased mobility and less restrictive fashions further enabled women to become agents of their own autonomy. However, such a woman was also subject to public scrutiny: to balance work and home, society demanded that she be coiffed and prepared to look her best at all times.

Women looked to Hollywood in the 1930s and 40s for inspiration on style. Cinema glamorized the art of dressing up, and placed a renewed emphasis on the vanity table as a site of intrigue and performance. As many aspired to obtain the “look” modeled by their favorite actresses, the booming cosmetics industry marketed a vision of the American woman as adventurous and open to experimentation. Popular magazines emphasized the dressing table as an agent for transformation, but with certain implications: women could be in charge of owning their appearance, and using it to their advantage, but were directed by a consumer culture that linked beauty and value. New additions to the vanity table supported this position: typical models now came with built-in lights, multiple drawers to hold cosmetics, and larger mirrors.

Continuing into the present, the vanity table remains an ubiquitous piece of furniture, though its appearance and relevance waxes and wanes according to the times. Often overlooked by collectors, these objects continue to play a significant role in society and culture. Its chameleonic ability to adapt to design trends also reflects the personalities of both its user and maker ñ making them time capsules of how we evaluated beauty, appearance, and interior design at any given era.

Erica P. Lome holds an MA in Design History from the Bard Graduate Center, and is currently a doctoral student at the University of Delaware in the History of American Civilization Program. She is also the Editorial Assistant for Winterthur Portfolio and is the Academic Programs Assistant at Winterthur Estate, Museum & Library.

-

- Assign a menu in Theme Options > Menus WooCommerce not Found

Related posts: