By Donald H. Pfister and Jennifer Brown, Harvard University Herbaria

Unless otherwise noted, all images courtesy of the Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants, Harvard University Herbaria / Harvard Museum of Natural History. Photos by Natalja Kent © President and Fellows of Harvard College

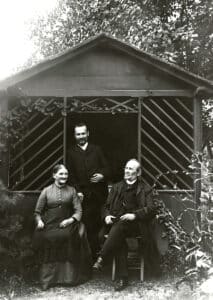

The Glass Flowers exhibit is one of the major attractions at the Harvard Museum of Natural History. This remarkable collection is the product of the father and son artists-naturalists, Leopold (1822-1895) and Rudolf Blaschka (1857-1939). These renowned artists and glassworkers created life-like models that allow museum visitors to experience both the familiar and the exotic. Their masterful work, informed by detailed studies of each plant from nature, employed inventive methods to shape and color glass; they developed methods to mimic the surface textures and colors of leaves, branches, and flowers.

Why did the Blaschkas produce this collection and who inspired them in this endeavor? To answer this question, we look deeply into the initiation of the project and the era in which the models were made.

The Seed is Planted

These soft-bodied organisms lose their life-like appearance when preserved, but the Blaschkas’ highly realistic models allowed people to observe and study invertebrate animals as they might appear in nature.

The presentation of plants in the museum setting presented a similar problem – think of a wilting bouquet, spent flowers in a garden or the favorite flower pressed between the pages of a book. For scientific study, plants are pressed and dried, and then typically mounted on paper to be stored in an herbarium. Goodale was planning exhibits for the newly formed Botanical Museum and, inspired by the zoological models, he realized that the Blaschkas would surely be able to transfer the techniques used to create the invertebrate animal models to create glass models of plants. Obtaining such a collection would be the cornerstone of his new museum.

Germinated with Funding and Finesse

For the next three years, the Blaschkas divided their time between producing glass models of plants exclusively for Harvard and invertebrate animal models for other institutions. In 1890, a contract was negotiated that allowed them to work only on the Glass Flowers. Following his father’s death in 1895 Rudolf carried on, and the Wares remained devoted benefactors.

No one could have anticipated that the project would continue until 1936 when Rudolf’s final models arrived at Harvard. Over the course of those fifty years, the Blaschkas produced 4,300 glass models representing 780 species of plants, fungi, and algae. What Goodale may not have fully realized was the precision and care the Blaschkas would employ in portraying every minute detail of flower and leaf structure. Such precision was honed by their scientific study of the plants they rendered. Indeed, each model is a three-dimensional portrait inspired by detailed study of a living plant.

Beneficiaries in Bloom

But why and for whom was this exceptional collection created? The exhibit was intended to teach, and was aimed not just at students studying botany but also for the general public.

Many other books aimed at introducing plants to the general public were published during the middle to late 19th century. Perhaps there was no period during which so many books appeared that were aimed at this audience of school-aged children and curious adults. For example, Familiar Lectures on Botany by Almira Hart Lincoln Phelps went through 17 editions and many printings from 1829 to 1872. Alphonso Wood, during the period between 1849 and 1889, successfully published a number of popular botany books. All this is to say that in the late Victorian period, at the time the glass flower collection was initiated, there was an eager public curious to see plants that they may have known from their studies but had not seen in real life. At that time even the banana and the mango, that we now take for granted, were considered rare and exotic.

The Master Gardener

Goodale’s vision for the Botanical Museum, and that of his successor Oakes Ames, was to introduce the general public to how people use plants and their dependency on them. To that end, materials were assembled to show the plants themselves and the products derived from them. The Glass Flowers provided a way to admirably present plants in the museum setting. Among the models from the Blaschka studio are different series created to illustrate diseased fruits, insect pollination of plants, and life cycles of fungi, ferns, and bryophytes. All of this was aimed at building public plant literacy. These models challenge the viewer to understand basic plant biology, structure, and reproduction. But, as one is drawn into the beauty of the models and the wonder they inspire, one is also aware that the makers were faithfully transcribing what they saw using materials and techniques they were constantly modifying to meet their exacting standards of verisimilitude.

The Glass Flowers came to be because of George Lincoln Goodale’s foresight, Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka’s masterful talents, and the Ware family’s support. The collection is a marvel of artistry, innovation, and scientific acuity. Upon seeing these models in person, one wonders how they are indeed fragile glass.

The Glass Flowers are on permanent exhibition at the Harvard Museum of Natural History located at 26 Oxford Street in Cambridge, MA. To learn more, click here: hmnh.harvard.edu

A new book about the collection is available now, Glass Flowers: Marvels of Art and Science at Harvard. This book is published by Scala Arts Publishers, Inc. in association with the Harvard Museums of Science & Culture. To learn more about the book and how to order, click here: ScalaPublishers.com/glass-flowers

Related posts: