By Judy Gonyeau, managing editor

Fotomat

Back in the days of 35mm film and the affordable Kodak Instamatic, getting that film developed took time – and patience. Most people would mail away their film to a developer such as Kodak and hope to get the pictures back in a week or two. Much different from the instant gratification brought by downloading and printing your own digital photos today.

In 1965, Charles Brown opened the first “Fotomat” in Florida, giving customers their photos just one day after they dropped off their film. Preston Fleet, a wealthy aviation enthusiast, and partner Clifford Graham, a gun-toting entrepreneur known for his “questionable” business practices, knew a good thing when they saw it. They bought out Brown and officially founded the Fotomat Corporation in 1967. Within just 18 months, there were 1,800 shops in operation.

The Fotomat “hut” was as bare bones as one could imagine. No bathroom (most employees worked out a plan with surrounding businesses to use their facilities), stacked with envelopes and paperwork, film for sale (Kodak or Fotomat brands), and other photography products for sale as well. Employees were forced to wear “hot pants” as part of their working uniform.

The early color scheme of the buildings featured a bright yellow and red that led many to believe Fotomat was owned by Kodak. Lawsuits forced a change to a color scheme of brick with a brown roof.

By the early 1980s, there were over 4,000 locations nationwide. Fotomat huts were literally located across the street from one another as franchisees staked their claim within a busy shopping district. It was almost impossible to go to any strip mall or large department store parking lot without seeing the hut in the parking lot.

However, the oversaturation of locations was not what killed the kiosk. Minilabs with one-hour turnover were popping up inside pharmacies and other businesses to process film while the customer shopped. Minilabs soon dominated the market, leaving Fotomat with just 2% of the market by 1988. The invention of digital cameras dealt the final blow. Fotomat was bought out by Konica with only 600 huts remaining.

Although Graham had divested his stock in Fotomat years before, his penchant for less-than-trustworthy dealings continued after his Fotomat years. He promoted a gold mining operation called Au Magnetics saying he could turn sand into gold. After being indicted for a list of crimes, Graham disappeared, leading speculators to suspect he may have been killed by an investor or was able to stay off the radar of arresting authorities.

Former Fotomat huts are now ice cream shops, shoe/watch/small item repair locations, a world-famous crochet museum, coffee shops, locksmiths, and even tailors. Even though other businesses are in the huts, just about everyone who remembers Fotomat knows exactly what those little buildings were at the start of automated photo production.

TRIPTIK

AAA, the American Automobile Association, was formed on March 4, 1902, when nine motor clubs with 1,500 members joined together and formed what would become the largest nationwide car club it is today. AAA sponsored road races on Long Island, New York, in 1909, produced hotel guides starting in 1917, offered driver safety programs at schools in 1920, and enhanced the driving experience across the U.S.

In 1905, AAA introduced a revolutionary tool for the traveling public: the portable paper road map. Even though road maps have existed since Ancient times, the AAA 20th century road map was geared toward destinations and how to get there from here. In those early days, most roads were dirt and gravel. AAA produced strip maps that showed which roads were automobile-friendly.

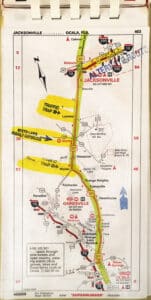

The strip maps were the precursor to the “TripTik.” According to www.aaa.com, “An agent would draw the route with a highlighter on a series of numbered maps, going through the route with the driver before they started. The end result was a guided route through a series of strip maps, called a TripTik.”

The first official TripTik was produced in 1937. In 1938, AAA started mass-producing pre-printed maps that would be put together in a spiral-bound notebook that the driver could easily follow from one road to the next. “These TripTiks were customizable too – AAA would also point out sightseeing, amusement parks, construction, heavy traffic, rest stops, gas stations, and all other points of interest to the traveler as well, and note as many or as few as the traveler chose.”

People would hang onto their TripTiks to update when they made another visit to that destination. You could even bring your TripTik back to the AAA office to have it updated to reflect any changes to the course.

There were special accessories for storing the TripTik in the car, cataloging trips with storage options, and the AAA hotel and motel guides with star-rated information on quality and amenities.

TripTiks are also collectible. Many travelers kept them to relive memories of the roads they traveled. Today, you can find TripTiks for sale for around $10+ depending upon condition and, in many cases, based on the trip itself. Nationwide trips, trips to iconic destinations such as Yellowstone Park or Niagara Falls, or following classic routes (think Route 66 or Route 1) to recreate a noted experience can also affect value.

TripTiks still exist today but in the form of AAA’s TripTik Travel Planner app. Plus, the paper versions can still be obtained and often prove to be particularly handy when your adventure takes you through those spots that only have spotty phone reception.

TOWER RECORDS

To Tom Hank’s son, Colin, Tower Records was a music mecca. Colin spent seven years creating the documentary All Things Must Pass as an ode to the business that coined the phrase “No Music No Life.” To him, “Tower sort of helped pave the way for your identity. For lack of a better phrase, music makes people, sometimes, where you sort of latch on to music as a way of identifying yourself or your tribe. I got that at Tower Records.” This company held court to anyone seeking to find their musical soul within a song, an album, liner notes, cover art, and local discoveries.

Founder of Tower Records Russell Solomon began selling records as a teenager in an effort to re-sell 78-rpm jukebox records from his father’s Sacramento drug store. In 1960, Solomon opened the first Tower Records at 2514 Watt Avenue. Here, and in the stores that followed, all staff members had a strong music knowledge base and could talk music with just about anyone and help customers with their selections

and collections.

From the 1960s through the ‘80s, Tower Records had more than 200 locations in 20 states and 18 countries with an annual sales exceeding $1 billion. Towerrecords.com discribes the stores this way:

“Upon entering a Tower Records store, visitors were greeted by knowledgeable aficionados and tall stacks of the latest albums near the front door. Long aisles contained thousands of titles in every imaginable music genre created. The store stayed open late and became evening hangouts for thousands of music fans, who would stop in and buy a few items as part of their nights out.”

In the documentary, Elton John talks about his experience at Tower Records. “Tuesday mornings, I would be at Tower Records,” John says in the film. “And it was a ritual, and it was a ritual I loved. I mean, Tower Records had everything. Those people knew their stuff. They were really on their ball. I mean, they just weren’t employees that happened to work at a music store. They were devotees of music.”

While this world-wide brand with local ties served as the place to hang out, there was a growth taking place that was never going to end – so they thought. In 1994, Solomon thought the change from records and CDs to digitized music available to everyone would be something they could deal with over time.

Tower Records invested in technology. They built hi-end audio listening stations in the store that let you preview vinyl and CD albums to try-before-you-buy. The stores expanded product lines past all things musical and offered services including coffee and food to entice visitors to stay and buy. But, eventually, in 2004, the company entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy for the first time. The aggressive expansion created massive debt, estimated to have been between $80 million and $100 million. On August 20, 2006, Tower Records filed Chapter 11 bankruptcy for the second time, in order to facilitate a purchase of the company prior to the holiday shopping season.

Tower Records is still alive online celebrating a rise in vinyl sales and using its cache of musical knowledge to guide collectors to see what is out there to build or add on to their collections.

You can also bulk up on Tower Records merch and get the latest issue of its magazine, Pulse.

Toys ‘R’ Us

Lazarus opened his first store, Children’s Bargain Town, in 1948. Business was brisk, but soon parents were handing things down, not picking new items up, as their second and third child came along. Lazarus decided to add a few inexpensive toys to his inventory to grow the business, then brought in a few more, and quickly realized the market for toys was very strong.

Fast forward to 1957 and Lazarus went “all in” on toys using the “Toys ‘R’ Us” name for his new toy stores. Refining his logo, he placed the “R” backward as if a child had written the name.

Far from a mom-and-pop shop, Toys ‘R’ Us was designed as the “supermarket of toys” for kids of all ages showcasing an abundance of makers, hobbies, games, and just about anything that would bring joy to a child.

Lazarus’ timing could not have been better as the economic boom took over the growing country. Over 75 million babies were born in the U.S. from 1946 and 1964, and each one needed toys. By the late 1950s, U.S. toy sales exceeded the $1 billion mark as Toys ‘R’ Us continued to expand.

In 1966, Lazarus sold his company to Interstate Sales and became the head of its toy division overseeing the Toys ‘R’ Us stores. According to The Washington Post, over the following 22 years, “Toys R Us grew to 313

stores, 74 Kids R Us outlets, and had opened 37 international locations.”

Geoffrey the Giraffe became the mascot in 1969 and morphed over the years to stay current, becoming one of the most-recognized store mascots in the world. The original Geoffrey was known as “Dr. G. Raffe” at the Children’s Bargain Town and was renamed by a store employee.

In 1974, Lazarus was once again in charge after Interstate Sales filed for bankruptcy. Lazarus sold off unprofitable divisions. Toys ‘R’ Us made its debut on the Stock Exchange in 1978.

The 1980s and 1990s saw a few changes for the store—including opening the first Kids ‘R’ Us and Babies ‘R’ Us stores—but sales were beginning to wane. In 1998, Walmart was listed as the top U.S. toy seller for the first time. There were signs that the market was shifting but Toys ‘R’ Us continued to expand, investing in real estate for its headquarters in 2001 for $36 million.

The toll of these changes led to closing all of the Kids ‘R’ Us stores in 2003 and Toys ‘R’ Us changing to a private company in a $6.6 billion leveraged buyout deal. Over the next few years, the company buys and sells other businesses and even tries to go public again to no avail. On March 14, 2018, the announcement from Toys ‘R’ Us stated it would liquidate and close or sell all of its 800 U.S. brick-and-mortar stores, but the business continues to have a presence online today.

The retailer “Kohl’s” recently announced it would be partnering with WHP Global’s Babies ‘R’ Us retail division to open locations within its stores in roughly 750-2,000 square feet of floor space. Could this mean we may be seeing more toys at Kohl’s? Time will tell.

Related posts: