by Bill Thornbrook

A smoldering debate over “clean coal” technology for modern power plants has pitted environmentalists against an industry that once dominated the U.S. energy supply. Although still used to fire many industrial steam generators, coal has largely yielded to natural gas, electricity, and oil burners for heating contemporary homes. By now, most Americans are less familiar with the combustible mineral that was once delivered by the ton down a chute into cellars tyrannized by monstrous furnaces that had to be fed coal every day and cleansed of ash.

In those receding decades of the mid-20th century, the king of coal was anthracite. American anthracite occurs almost exclusively in the hard-coal region of northeastern Pennsylvania, from Pottsville in the south to Carbondale in the north, centering on the Wyoming Valley between Wilkes-Barre and Scranton. Only one percent of the world’s coal supply is classified as anthracite, even including deposits in Germany, China, and Wales. Pennsylvania has the lion’s share.

Perhaps because anthracite is actually hard to ignite, its potential as a home heating fuel was not considered until around 1800. It was soon thereafter adopted as a hotter, cleaner-burning alternative to wood. Compared to ordinary “soft coal,” anthracite is two or three times more expensive, but its heat output is much higher with less soot and ash by-products.

By the early 20th century, anthracite was the favored heating fuel for homes across the northern U.S. Pennsylvania mines were producing up to 100 million tons of it per year. The Glen Alden Coal Company, one of the largest, cleverly trumped rival suppliers by marketing their trade-marked ìBlue Coal,î a high-grade anthracite enhanced with a patented blue dye. They shipped the coal across much of the continent in their own railroad cars.

Long before its primary importance as a fuel, chunks of gleaming black anthracite attracted the attention of earlier people. Hard coal had now and then been carved in China and in Europe through the millennia. In 1960, an amateur archaeologist working near Williamsport, Pennsylvania, some 70 miles from the anthracite region, found a small bit of coal that had been carefully shaped and polished by a Native American perhaps three thousand years ago. This find represents one of the first known uses of coal in the New World.

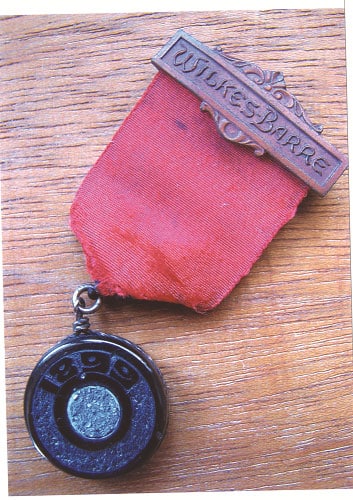

Much, much later coal miners in the Wyoming Valley took up the pastime of carving small whimseys and souvenir novelties from pieces of anthracite in their off hours. Coal carving supplemented many a miner’s income during the Depression years. Disabled miners offered the products of their carving skills in an attempt to replace lost livelihoods. A few non-miners in the coal region set up small workshops to produce carved coal products as a full-time profession.

The best known of these professional coal carvers was Charles Edgar Patience (1906-1972), an African-American who learned the craft from his father. Patience, a native of Wilkes-Barre, acquired a reputation as a coal sculptor. Several of his larger works, including life-sized busts of presidents Washington, Lincoln, and Kennedy, went to major museums. His two-ton coal altar-piece graces the chapel of Kings College in Wilkes-Barre. He routinely carved and sold thousands of smaller gift items and jewelry creations that found their way into private hands.

One of the last commercial carvers was Frank Magdalinski, whose Anthracite Coal Crafts near Wilkes-Barre was still retailing hand-made items through several local tourist attractions in 2011. Frank, who began carving with his father in the 1930s, was at that time planning to retire.

Many anonymous part-time carvers also contributed to the souvenir trade in carved anthracite products. Working the coal did not require any special tools or training. The ideal raw material was an unweathered lump of especially hard anthracite that showed no cracks or impurities. The coal is brittle and prone to fracture, but can be easily hand-worked by hacksaw, drill, file, chisel or knife, sandpaper, and finer grits for final polishing. Shops usually relied on a lathe to speed up the operation. These processes released copious amounts of fine black dust, which is not only messy but also dangerous to the lungs.

Though the supply of anthracite souvenirs has dwindled over recent decades as the coal mines closed and carvers retired, enough of these items remain in circulation to keep collectors happy. They show up occasionally in antique shops (sometimes unrecognized as coal). Some are always available on-line at reasonable prices. The more desirable pieces are lathe-turned or carved in-the-round, often finished with chip-carved sections that lend a contrasting texture to the polished surfaces. Less appealing to collectors are flat slabs of coal simply decorated with sand-blasted designs produced with steel stencils.

Buyers should also be aware that the majority of coal items currently offered on the Internet are not authentic hand-carved anthracite. More common today are compressed coal products, in the shape of model coal-breakers or other buildings, tired miners wearing head lamps, endearing children or animals, etc. These mass-produced items are actually cast from a slurry of resin-infused coal dust that has been molded and hardened. By contrast, genuine hand-carved anthracite usually exhibits formal simplicity, but is always jet-black and often polished to a high sheen. Also look for fine hairline fractures or small flakes along the hard edges of real coal. Asian coal carvings also appear on the market, but generally are much more intricate sculptures that include zodiac animals rendered in typical Chinese style.

Related posts: