by Melody Amsel-Arieli

Under a spreading chestnut-tree

The village smithy stands;

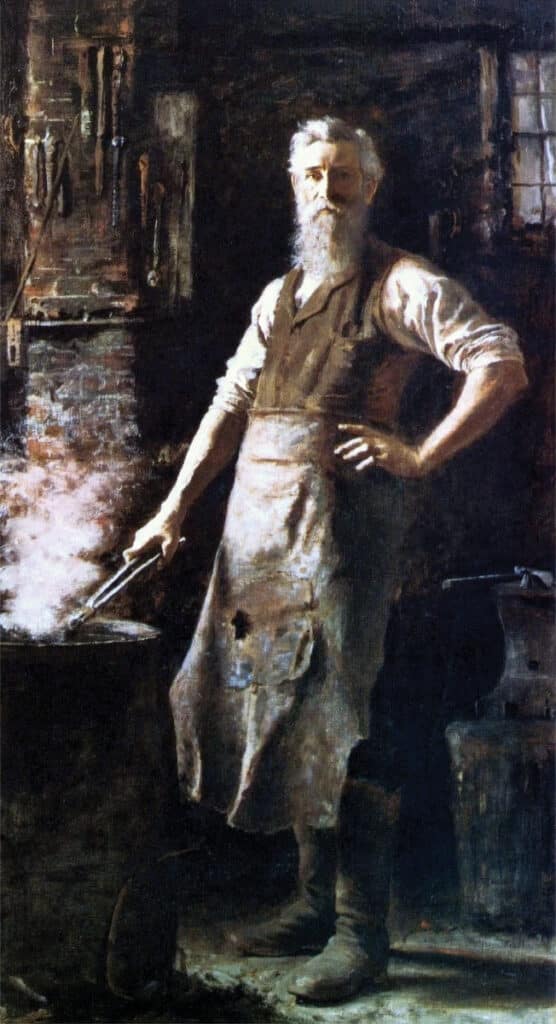

The smith, a mighty man is he,

With large and sinewy hands;

And the muscles of his brawny arms

Are strong as iron bands

– The Village Blacksmith, Longfellow, 1842

Blacksmiths have wrought objects from iron for thousands of years. Metalworking, however, harks back further still. Egyptian artisans, for example, worked gold and copper, which occur in nearly pure states. Lacking knowledge, however, they could not access iron from minerals like magnetite and hematite.

So discovering an iron dagger in the 3300-year-old tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun was beyond belief. However, through advanced x-ray techniques, scientists determined that it had been formed from metal auspiciously rained down from heaven—an iron meteorite.

Ingenuity, Breadth, and Depth of Iron Workings

photo: Cowan’s Auctions, Inc.

A millennia later, the Hittites discovered that smelting (high-heat melting) iron-rich minerals extracted workable iron oxide. Their deadly iron daggers, swords, spears, and chariot enhancements, unlike earlier, brittle bronze ones, withstood shattering on impact. Moreover, when mended, they became stronger still. As a result, the Hittites not only scourged neighboring tribes but ushered in the Iron Age.

As this earth-shaking technology spread, blacksmiths, named for the black-iron goods they forged, flourished in communities worldwide. Their tools—small smelting furnaces, hand-forged implements that drew, bent, punched, rolled, and flattened glowing-hot creations on anvils—were simple. Yet to many, transforming crumbled stones into amazingly durable, life-saving objects seemed almost magical. In fact, in some societies, they were accused of witchery.

Through the Middle Ages, a time of great warfare, blacksmiths routinely wrought an innumerable number of arms, armor, and horse gear. In addition to creating crucially important agricultural implements like iron-pronged pitchforks, harrows, and plowshares, they forged hearthside hooks, tripods, cleavers, choppers, flesh forks, roasting jacks, and mini-cranes (which swung pots away from flame). Through more innovative techniques, they also fashioned cast-iron cooking pots, cauldrons, and kettles. Because these works were so costly, they were not only repaired repeatedly, but often passed from one generation to the next.

Initially, many forged pieces were left unadorned. As their craft evolved, however, blacksmiths often became more imaginative. Scottish broad swords, for instance, sometimes featured prominent initials as part of their pierced hilt designs. Broad, ironclad doors and iron-wrapped chests, in addition to offering security and protection, commonly featured pleasing ornamentation. In time, architectural elements, like railings, window grilles, banisters, fireguards, and garden gates, often bore ornate, scrolled, flowered, or lattice-like designs.

Functional fireplace andirons typically featured graceful, turned finials above handsome, scrolled feet. Pierced ladles displayed finely engraved handles, while forks and skewers included delicate scrolling adorned with charming, wound-wire hearts. Additionally, chandeliers, wall cartouches, and sconces sometimes featured bits of ornamental ironwork.

Demand for wrought iron reached its peak at the height of the Industrial Revolution, especially for building bridges, railway tracks, steam locomotives, and ironclad warships. Blacksmiths also wrought everything from nails, nuts, chains, rivets, wire, and wagon wheels to stoves, grates, locks, lanterns, torch holders, tools, smoothing irons, and goffering irons – which fashioned frills and flounces in starched linen.

Forging in the New World

Across Colonial America, where iron ore occurs in abundance, blacksmiths smelted, smithed, and mended work, agricultural, and domestic tools vital to the fledgling nation. Some labored at isolated points along popular travel routes, offering on-the-spot, horse-related and carriage repair services. Others, lured by homes and free land as incentives, set up their dark, smoky shops on the edge of rural communities.

Their work was long, hot, and hard. After stoking and lighting their forges, they maximized their heat by blasting them with handheld bellows. Once their fires roared, they heated bits of smelted iron from red and orange-red to orange-yellow, the ideal heat for forging. Then, steadying their molten mass on anvils, they (or an apprentice) struck it into shape with massive sledgehammers.

Though smithing was difficult, work was plentiful. As a result, few blacksmiths needed to supplement their incomes with farming. In fact, many eventually became wealthy, leading members of their societies.

With the advent of inexpensive, low carbon steel in the mid-1800s, followed by mechanical production of countless copies of identical designs, the need for wrought ironwork declined considerably. Yet architectural elements, brightly painted or incorporating ornate, cast-iron sections, remained popular.

horseshoe forged by Robert Fitzsimmons (later unprecedented winner of 3 world titles), while apprenticed to his blacksmith father, realized $836.50 in 2012 photo: Heritage Auctions

As American settlers spread westward, blacksmiths came along. In addition to tools, wheels, and farming implements, they forged scores of identifying cattle branding irons. History buffs may also find their hand-forged horseshoes, hitching rings, bridle bits, stirrups, spurs, and snow knockers (used to knock ice and snow from

horseshoes) desirable.

A Plethora of Collecting Options

Cooking and baking fans, as well as interior decorators, may find forged domestic gadgets enticing. Who wouldn’t welcome vintage ice tong, wafer iron, spoon dipper, dough scraper, wheel pie crimper, hat hook, or candlestick accessories in their rustic, shabby chic, traditional, or colonial-style homes?

photo: Cowan’s Auctions, Inc.

Collectors with agricultural roots may cotton up to wrought iron-teethed rakes, carcass splitters, cradle scythes, single-handed sickles, or silage-slashing pumpkin choppers – especially ones rust-free with original wooden handles. Fishing fans may find 18th century eel spears or fish grabbers (which helped land fish) fascinating. Some, on the other hand, seek long, spear-like harpoons, fine not only for fishing, sealing, and whaling – but also in warfare.

Others hunt for vintage battle-axes, war scythes, daggers, pike heads, or halberds, popular from the 14th through the 16th century. These fearsome pole weapons, featuring wrought iron ax blades topped by spikes mounted on long shafts, were doubly versatile. Added hooks at their back dealt with mounted foes.

To some, ceremonial axes, borne by early 18th century festive Saxony Guild miners, are even more arresting. Scores feature wooden hafts inlaid with white staghorn, scrimshawed plaques depicting miners at work and worship. Others, in addition to off-set, decorative, pierced angular blades, feature staghorn plaques engraved with foliage, human figures, crossed pick-and-hammers, and the crowned arms of Saxony.

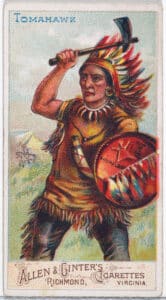

Tomahawks, single-handed, forged axes prized by Native American tribes, including Mohawks, Sioux, Iroquois, and Cheyenne, also muster great interest. Despite their dreadful connotations, explains George P. Belden in Twelve Years Among the Wild Indians of the Plains (1875), these implements “are seldom used by Indians as weapons, and, notwithstanding they passed into history as a deadly instrument, they are more for ornament than use.” Ones featuring simple hatchet-like heads with plain, wooden handles are fairly common. Those featuring porcupine quillwork, dramatic beaded drops, punched blade designs, or attractive hardwood hafts, however, are more desirable.

Tomahawks traced to a particular blacksmith or military engagement, such as the Battle of Little Big Horn, are extremely collectible. So are forged arms traced to the Revolutionary War, like a single-edged knife blade and shot chain set, possibly used by General Benedict Arnold’s forces during the Battle of Valcour Island, New York in 1776.

photo: Heritage Auctions

Whatever their choice, collectors value hand-forged implements not only for their historical worth and stark beauty but also because they reflect every day, long- ago lives. A set of wooden 19th century ice skates, featuring elf-like, curled metal tips, for example, may show visible wear. A heavy, sheet metal weathervane may boast original painted stencil work—or be pocked with bullet holes.

Prices vary widely. Though small hand-forged works in good condition may fetch under $100, fine, older ones typically command many times more. Rare, unusual finds, like a 20th century patented “garden rake” style golf club, a 19th century high-wheel “boneshaker” bicycle, or a 17th century toe-to-heel steel plate designed to protect the grave diggers’ feet from strikes to the boot made by their spades, are often the most costly—and most collectible—of all.

Related posts: