By Douglas R. Kelly

campuses in the first half of the 20th century.

There are few product names in the games and sporting goods industries that can match “Frisbee” for sheer recognition power. We don’t say, “Hey let’s play Monopoly” when we mean backgammon, and we don’t ask a friend to go out and “shoot some Wilsons” when we mean hoops (basketball).

But the word Frisbee has come to mean any flying disc made by any company, so even when we head out to play catch with a disc made by Franklin Sports or Aerobie, we say, “Let’s go play Frisbee.” The word entered our vocabulary more than 60 years ago, and the company that started it all has enjoyed branding success for which most manufacturers would give their eyeteeth. It has led to countless arguments and lawsuits over the years as competitors have tried to come up with names that are as memorable as Frisbee—some of them coming a little too close for comfort, while others just stole the name outright.

Re-purposed Metal

Frisbees weren’t always plastic. The earliest flying discs were made of metal, and they were never intended to be thrown into the air – they were designed to hold pie. Starting in the late 19th century, the Frisbie Pie Company, which was based in Bridgeport, Connecticut, sold its products in metal tins measuring around nine and a half inches in diameter. Most sources agree that it wasn’t long before workers at the bakery were chucking the empty pie tins back and forth on their breaks, along with students at Yale University, in nearby New Haven. (The Frisbie Pie Company also made cookies, sold in tins, the lids of which reportedly sailed back and forth along with the pie tins.)

Anything that’s shaped like a disc can be scaled through the air, and there are tales of people in other parts of the country doing so. One was Fred Morrison, an inventor living in California who liked to throw paint can lids and pie tins around as a kid. In the late 1940s, with his business partner Warren Franscioni, Morrison started experimenting, first with metal and then with plastic, as he tried to come up with a disc that would fly well and be durable enough to last more than a few throws. The two men formed a company that they called Pipco, which was short for “Partners in Plastic.” Their first plastic disc, the Flyin-Saucer, was fairly crude by today’s standards, but they worked at refining the design. In the early 1950s, after Morrison and Franscioni had parted company, Morrison formed a company, American Trends, which produced an improved version of the Flyin-Saucer.

The name Frisbee hadn’t yet entered the frame, as Morrison next came up with the Pluto Platter, which was a substantial improvement flying-wise over the Flyin-Saucer. The Pluto Platter eventually became the basis for the Frisbee of the future. In 1955 or 1956, Morrison met and partnered with Rich Knerr and A.K. Melin, the founders of the Wham-O company in southern California. Together they introduced the first flying discs bearing the Wham-O name in early 1957. Shortly after hearing that students at Harvard University used the word Frisbie to describe the throwing of pie tins around the campus, Knerr adopted the word for his company’s flying disc. He actually spelled it incorrectly—Frisbee—but that was the name that went on to become synonymous with the flying disc.

(Wham-O also would later score major hits with toys such as the Superball and the Hula Hoop.)

From a branding point of view, the names Flyin-Saucer and Pluto Platter have a lot going for them. Both describe the shape of the product and both capitalize on the space/science fiction angle that naturally was associated with the product. But Knerr (and perhaps Morrison and Melin) saw something (and heard something) in the word “Frisbee” and took a chance on it.

Much More Than a Fad

Frisbee sales were slow at first, but as the 1960s dawned, the plastic saucers increasingly were seen flying through neighborhoods all across the U.S. The idea that the Frisbee was some kind of fad faded as time went on and sales started to go through the roof.

The Frisbee was a toy, but it now began morphing into a sport. Most people were casual Frisbee players—throwing and catching the discs for fun—but competitions that involved distance, accuracy, and other action had been around since the 1950s. Seeing the success Wham-O was having, a number of competitors got into the act and started making their own versions of the Frisbee. It’s unclear whether Wham-O actually owned the rights to the name Frisbee at the time, given the number of people involved in the product’s creation and development, along with the fact that the word Frisbee had been in common usage in the northeastern U.S. for a number of years, going back to the Frisbie pie tin days.

Still, most competitors refrained from calling their product a Frisbee. This resulted in a lot of creatively named discs entering the market. Skyway Products produced the Finger Flinger; Superflight produced the Aerobie Superdisc; Voss-Reynolds put out the Turbo Disc; C.P.I. introduced the Saucer Tosser; Wiffle Ball made the Wiffle Flying Saucer; and many more came and went as time went on.

for their sharp artwork.

During the 1970s, Brumberger came close to infringing the name with its Giant Frizzy, but others took a more direct route. Around 1959, a New York company, Empire Plastics, came right at Wham-O with its Zolar Flying Saucer, which featured the name Frisbee on the packaging. Empire then introduced a disc that had the word Frisbee on it in large block letters. It also showed two boys playing catch, with the shirt of one of them sporting a large “Y,” which some believe to be a reference to Yale University – a school that had been right in the center of the pie tin/disc throwing activity for years.

As time went on, Wham-O defended its trademark, sometimes settling with competitors by requiring them to cease and desist, as well as to hand over to Wham-O equipment used in the manufacture of their products.

Developing Sports

Guts Frisbee was one of the earliest games to be developed, going back to 1958. Generally, five players on each side attempt to throw the disc through the opposing side’s goal space without the disc being caught.

Ultimate Frisbee got its start in the late 1960s as a high school game, which then caught on in a big way on college campuses. Ultimate is played between two teams on a field with end zones, and the object of the game is to score by catching the Frisbee—a “pass”—in the other team’s end zone. Today, there are Ultimate Frisbee leagues all over the U.S., including at many colleges and universities.

The king of Frisbee sports may just be disc golf, which has seen huge growth since the 1960s. Disc golf is just what it sounds like: players throw discs toward a “hole” (usually a chain link basket) on a dedicated course. The score is kept, much as in the standard game of golf, according to how many throws each player makes before putting the disc into the basket. The player with the lowest total score (for the 9-hole or 18-hole course) wins.

Disc golf is perhaps the best example of a long-time debate that has taken place regarding the words “Frisbee” and “disc.” Although it’s known both as disc golf and Frisbee golf, Wham-O is just one player in that market. “Wham-O does a little bit in Frisbee golf because it would take a lot for them to try to get a piece of that market,” says Victor Malafronte, author of The Complete Book of Frisbee and the “Original World Frisbee Champion” from his victory at the Invitational World Frisbee Championships in 1974. “Now there are six or seven big companies that are making golf discs. You have Discraft, you have Innova, you have Dynamic Discs, you have Prodigy.” In general, golf discs are smaller and are more dense and flexible than standard Frisbees, characteristics that enable a golf disc to be thrown further and with greater accuracy.

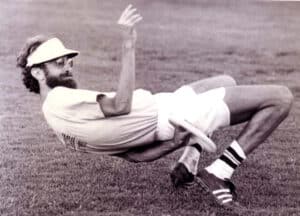

The growth of Frisbee and related games and sports has resulted in the creation of organizations to manage and facilitate participation. Even the names of these organizations point up the Frisbee versus disc question. Dan Roddick, a multiple-time Frisbee champion and well known as “Stork” in the Frisbee world due to his height and sometimes twisty playing style, grew up in Pennsylvania. He had his first contact with a Frisbee when he received a Pipco Flyin-Saucer as a Christmas present when he was five years old. He served both as director of the International Frisbee Association (IFA) from 1975 to 1982, and as president of the World Flying Disc Federation from 1986 to 1992.

Does he see the names of these organizations as reflecting the growth of disc sports and the fact that Wham-O was getting more and more competition from other manufacturers? “Absolutely. And the interesting twist to it is that my first journalistic effort, when I was at Rutgers University, was Flying Disc World. So I probably put in print the generic term first. Many of the early things done under the aegis of the IFA were done by Wham-O, exclusively. It was all Wham-O money. Once they put me in place there [at the IFA], I had regional directors out there, I had Frisbee World magazine, we had the Frisbee World Championships … Frisbee Frisbee Frisbee. It made sense for Wham-O, because any publicity that came with the activity, guess where the shelf action was? Frisbee.

“But as the market started to broaden, with companies like Innova and Discraft and others beginning to get a foothold—first just through enthusiasts and then

actually getting shelf space—and going into major [outlets], it just increasingly made sense for it to become a generic sport, like virtually all others. Whether it’s surfing, or golf, or whatever … they all work with various manufacturers. That was a very hard transition for Wham-O to make because it’s good to be king! Why share lunch, especially when you’re buying lunch? A hard transition, and I was right in the middle of it, and I had my critics on either side. In retrospect, particularly with people in the sport, it gave me a lot of latitude. I was still working for the company that made Frisbees (Mattel Sports owned Wham-O, at that point) and I was the director of the World Flying Disc Federation. You can imagine that that would raise eyebrows.”

Disc Collectibility

Early flying discs, such as the American Trends Flyin-Saucer and the Pluto Platter, often come with big price tags. They can run into several hundred dollars, and occasionally into four figures. But with more than 70 years of flying disc history to dig into, there’s a huge number of great Frisbees out there waiting to be found.

Condition, unsurprisingly, is king with older discs. “You can get a Pluto Platter for anywhere from $10 for a common color one that has dog bites all over it, to thousands of dollars for a pristine example in a rare color,” says Dan Roddick. “If you just want a cool Pluto Platter to put in a frame and hang on the wall, you can get away pretty cheap. But if you want a significant, important disc that potentially will gain in value, then you need to become more knowledgeable and find out what the key components are. When someone tells me something like, ‘I have an old Mars Platter that we used to throw around up at the camp for years, would you like it?’ That might be interesting to see, but if it’s a beat-up and dog-bitten disc, I generally advise them to keep it as a family heirloom and enjoy it because it usually doesn’t have much value as a collectible.”

Many (though not all) discs came in packaging of some sort, whether a plastic bag attached to a header card, or a cellophane-wrapped piece of cardboard. The older the disc, the less likely it is that it’s still in its packaging. If it is, depending on the condition of the packaging, the asking price can easily double.

Stickers, on those discs that originally came with them, are another challenge. Some collectors consider a disc incomplete if it doesn’t have its intact original sticker in its center. These often gradually wore off discs due to repeated use, of course, but others were removed intentionally by owners intent on improving a disc’s flying performance. Either way, an original sticker not only looks sharp, but also can help in identifying the model (name) of the disc.

Victor Malafronte thinks that one of the “holy grail” Frisbee items isn’t even an actual disc. It’s an original pie case (also known as a pie safe) from the Frisbie Pie Co. in Connecticut. These wooden cabinets were used by the company to display the product, and likely were often thrown out when a shop closed down or stopped carrying Frisbie’s products.

As a collectible, a flying disc has something of an advantage over other kinds of items when it comes to display: they make for very interesting “art” when hung on a wall, and due to their size, they can be interchangeable. Put a push pin in the right place, and hang up your 1959 Pluto Platter or 1973 C.P.I. Saucer Tosser, and you have the beginnings of a Frisbee exhibition. But these things tend to multiply, and they can get out of hand before you know it. “Nobody understands … relatives and friends will think you’re a hoarder,” says Roddick, “if you just take them into a back room and say, ‘Look at this, I have 800 Frisbees.’ They’re going to think you’re crazy. But if you organize it in a rational way and say, ‘Oh, I specialize … I only have discs that have (for example) states on them. I have one of every state, here’s the wall with the states on it. I don’t have them all yet, and I’m really looking for a Wisconsin.’ If that makes sense, then you’re not a crazy person.

Probably the most fun was collecting novelty discs … things like the B.F. Goodrich tire, the flying pickle, the flying cow chip, the sailing sombrero. People love these … they see these and go, ‘Oh that’s really cute, it looks just like a pizza. And it can fly!’”

Douglas R. Kelly is the editor of Marine Technology magazine. His byline has appeared in Antiques Roadshow Insider, Back Issue, Model Collector, and Buildings magazines. His Frisbee collection is threatening to take over his office.

Digging Deeper

Many books have been written about Frisbee, but two stand out for their historical content and details on specific discs. Dr. Stancil E.D. Johnson’s Frisbee: A Practitioner’s Manual and Definitive Treatise, published by Workman Publishing Company in 1975, offers a picture of the world of Frisbee in the 1970s. And The Complete Book of Frisbee, written by Victor Malafronte and published by American Trends Publishing Co. in 1998, examines in-depth the history of Frisbee and features a detailed identification and value guide to collectible discs.

The website www.flyingdiscmuseum.com is full of photos and descriptions of discs of all kinds, sizes, and eras, and is a great way to get the lay of the land Frisbee-wise. Also, check out www.marvinsflyingdisccollection.com.

Related posts: