by Judy Gonyeau

with heavy reference from Defining New Yorker Humor by Judith Yaross Lee

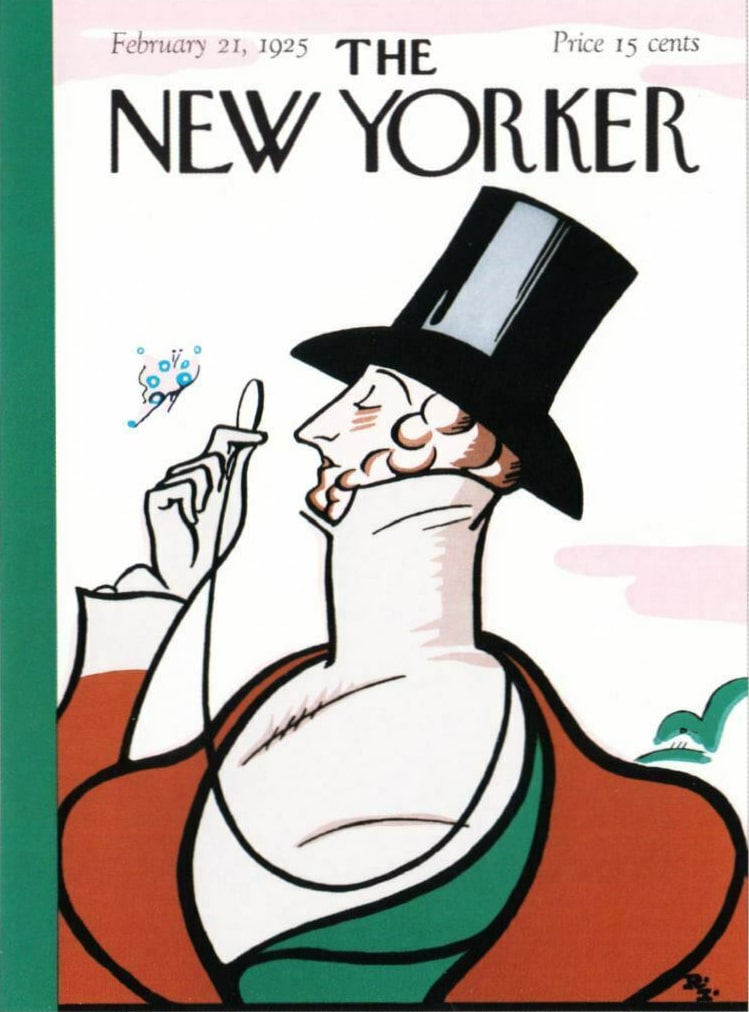

Launched in 1925, The New Yorker is a mostly-weekly magazine dispersing information through a myriad of journalistic articles, commentary, satire, fiction, criticism, its famous cartoon comments, and poetry. It continues to be renowned for its journalism covering everything from politics to popular culture, social issues, and pressing topics of the day.

As The New Yorker approaches its 100th anniversary in 2025, it is the magazine’s original humorous take on so many elements of life that continues to draw New Yorkers and readers from around the world.

Satire From The Start

The New Yorker’s wry approach to life in New York was originally based on its namesake: the New Yorker. Not just any New Yorker, but the ones who were forming a new, sophisticated society built on an influx of new money from new industry. These men- and women-about-town were making a name for themselves as trendsetters, building a “World of New York” as the center of their cultural, social, deal-making and -breaking money-driven town.

News centered around the questions New Yorkers and others wanted to know. What was the “new” New Yorker doing? Saying? Wearing? Buying? Reading? Eating? Talking about? Investing in? Being entertained by? Flirting with? Sleeping with?

All these questions were swimming about in the mind of Harold Ross who, with his wife and New York Times Reporter Jane Grant, wanted to create a cosmopolitan magazine with a good amount of sophisticated humor – one that would allow the reader to gain not only information but insight into this World of New York with a nod, a wink, a chuckle, and from time to time, a shock.

The New Yorker Persona

Ross became the Founding Editor for The New Yorker in 1925. His approach to creating a one-of-a-kind New York magazine was to reflect the haphazard goings on of the New Yorker he was talking to and about—the newly created class of gentlemen (and women) in a world they had no control over.

To kick-off the publication and establish its unassuming yet acerbic tone, Ross gave a forthright view of himself and the office in his first editorial. Here, Ross describes an almost physical comedy sketch talking about the start-up of the magazine by using a metaphor about his secretary and her command of the monstrous-sized telephone switchboard. Just as final production of the first issue was about to go to press, she left her job to get married in the middle of the day – leaving bells and rings blaring. Ross was left trying to figure out the written directions to use the “Jumbo Jr.” that he said “pertain to … a deceased cousin of the incumbent,” referring to his former secretary. After several attempts to tame the beast, he was able to get it under control just in time to get the first issue published, noting that “This does not leave one unshaken, of course, and at this point, [the] doctor advises a couple of weeks’ rest.”

Another founding element present from the beginning was the construction of a reputation for being “in the know,” and presenting only the latest and greatest to the reader. By divulging this with a conversational approach and using illustrative writing, the magazine fostered a “private” relationship between itself and the reader, The New Yorker became the go-to source for what was happening within society, delivered weekly with a hefty dose of sarcasm.

Ross established its readership area as the sophisticated realm contained in the five boroughs of New York. Why go anywhere else?

Using Humor to Disguise

Just as much as New Yorkers remained aghast at the content in the magazine, they were also continually astonished at revelations regarding its management of production. The offices of The New Yorker were continually portrayed as a work-in-chaos, and was described by writer Lois Long in 1927 as “those dear days when a group of talented young people struggled for the success of a little-known weekly … completely ignorant of how to use the telephone even if the distracted operator had ever been able to find any of us.” Long then wrote that Ross’ “greatest delight was to move the desks about prankishly in the dead of night. The result was that you could easily spend an entire morning, which you might have spent—God forbid—in honest labor, running up and down the stairs [and even in the elevators] looking for your office.”

By continually portraying the magazine’s management style as haphazard at best, Ross and succeeding editorial staff preserved the persona well past Ross’ tenancy (from 1925 until his death in 1951) as the standard way The New Yorker did things.

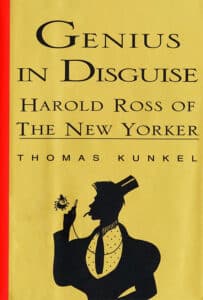

Ross was regularly referred to as a bumbling, anti-feminist, stingy, inept, undisciplined, “high-school dropout and wastrel newspaperman” (Earl Rovit, 1985), and “the unlikeliest of candidates to found a magazine that would place the best modern American humorists between slick covers and draft the manifesto under which The New Yorker would prosper,” (Sanford Pinsker, 1984).

Those who worked with Ross continued to keep up the talk about his incompetency—notably author and illustrator James Thurber—to the point of almost starting a war amongst the staff. Author and Editor for The New Yorker E.B. White and his wife Katherine took great offense to Thurber’s piercing (yet funny) book The Years with Ross (1958), saying that it caused “much sorrow and pain around the shop,” and thought Thurber was using it as a form of retribution. Katherine White even drafted a letter to Helen Thurber in 1975 regarding James Thurber’s assertion that “Ross was an illiterate clown” by saying “He was one of the most literate men I’ve known. “He wrote awfully well himself and was a wonderful editor.”

Katherine’s husband E.B. White wrote in a never-published history of The New Yorker that Ross “was a genius at encouraging people.” The Whites considered Ross the “hero” of the magazine.

Unveiling

As noted, the facts regarding the establishment of The New Yorker’s wry approach to its covered topics were obscured, kept hidden, and, frankly, lied about regularly. Books written about The New Yorker from such “insiders” as James Thurber, Margaret Case Harriman, and Brendan Gill, among many other writers were filled with the sometimes snarky tone that was The New Yorker’s signature style. Oddly enough, it was writer and illustrator James Thurber’s 1958 book The Years with Ross that was taken as the most reliable eyewitness account of The New Yorker’s office antics from the time it launched until the 1990s.

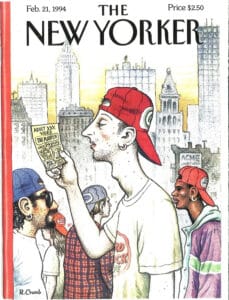

In advance of its 70th Anniversary in 1995, The New Yorker opened its archives to scholars in 1994, albeit a heavily edited and at times unverifiable version of the facts. Once the archives were opened, the truth about Ross that was hidden for over 69 years came to light. The biography Genius in Disguise, written by Thomas Kunkel, followed quickly thereafter in 1995, finally revealing the Founding Editor as a sharply skilled humorist and editor who carefully reviewed every aspect of the magazine’s content week after week.

Illustrative Content: The Blend

The cover image for The New Yorker has always been and likely always will be an illustration of some sort or another, and Eustace Tilley its favorite subject. Using the drawing talents on his staff and contributors, Ross felt an illustration could stretch the cover message beyond a photo through the use of artistic license.

Ross was the first to use illustrated humor within the editorial copy to drive home a particular point or carefully place a wink to the reader. Ross was successful because of his innate sense for identifying what drawing was best suited for factual vs. ficticious content. He used different illustrators for different articles because he felt their style of drawing suited it better than someone else’s.

The cartoon became the center of a thought that had been, or sometimes not, put in writing. This changed the role of comic art from just a representation of something written to an expression or commentary all by itself.

Illustration was also allowed to interact with copy, with cars crashing into copy when reporting on races to characters talking back to paragraphs as if to defend themselves. This was a way to present all sides of a topic without having to present it as a sidebar or talk about it in a separate article.

The Stand-Alone

The use of stand-alone cartoons not part of a story came about in the 1930s. These gave the reader a quick nod and a quick wink representing something that could be told quickly and succinctly. Most of the earlier comedic examples centered around the man of the house and the cacophony of activity and social pressures reeling around his daily life, or as Lee put it, “tales of neurotic little men driven insane by jumbo women and modern life – especially things technical or commercial.”

In today’s The New Yorker, stand-alone cartoons continue to be used as its own form of content. The editor(s) who are charged with selecting cartoons of commentary on current news or trends take their task very seriously. Not only do they select “winners” on a daily basis, but they act as foster illustrators to those who show promise.

The Talk

One of the earliest and most influential columns was (eventually) called “The Talk of the Town,” sharing the news and information that most often turned a New Yorker’s head. “Talk” mixed the notes of the week with carefully constructed illustrations drawn to drive home a particular point.

The column proved to be so popular that by May of 1928, it commanded a full five pages of editorial space in every weekly issue. The purpose was to offer advice on what popular entertainment event was worth viewing, share light news reports, and of course comment on society through gossip. The column did not have a byline, preferring to suggest that all information came from well-placed “insiders” who could scoop a story taking place just about anywhere in the city.

The Magazine also offered a number of quips throughout its pages called “Comments,” or really humorous asides placed as a callout within a fact-based or fictitious article, often accompanied by an illustration. These were written by editorial staff – anonymously.

Those Great Early Illustrators

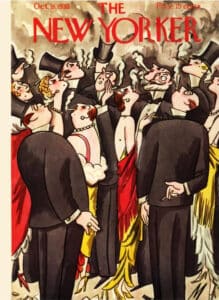

The artists who established the style of illustration that would drive The New Yorker forward as a must-see magazine for all New Yorkers set a tone of understated irony. Rea Irvin’s first cover portrayed the New Yorker as Eustace Tilley. She went on to create the masthead for “Talk of the Town.” Johan Bull was first to illustrate the copy with drawings focused on the “point” of the commentary using a wry approach.

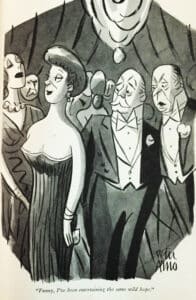

Peter Arno and Helen Hokinson lent a more conservative tone to their illustrations, preferring to show attractive people in fashionably correct settings. Arno’s sharp lines and ability to put noses in the air made him a favorite for many years, with his focus on the more testosterone-driven humor of male New Yorkers. Hokinson tended to work on “women (who) appeared slightly befuddled, but Hokinson never ridiculed her creations for their inability to grasp the utilitarian world. … She loved women of the sort she portrayed,” as reported by R.C. Harvey in The Comics Journal.

Other names that contributed to the magazine over its long tenure include Barry Blitt, Julian De Miskey, Alice Harvey, Georgia O’Keefe, Garrett Price, Perry Barlow, Mary Petty, Françoise Mouly, Frank Model, George Booth, and William Steig (also the creator of Shrek). Just google any of these names for great examples of The New Yorker’s view of the world.

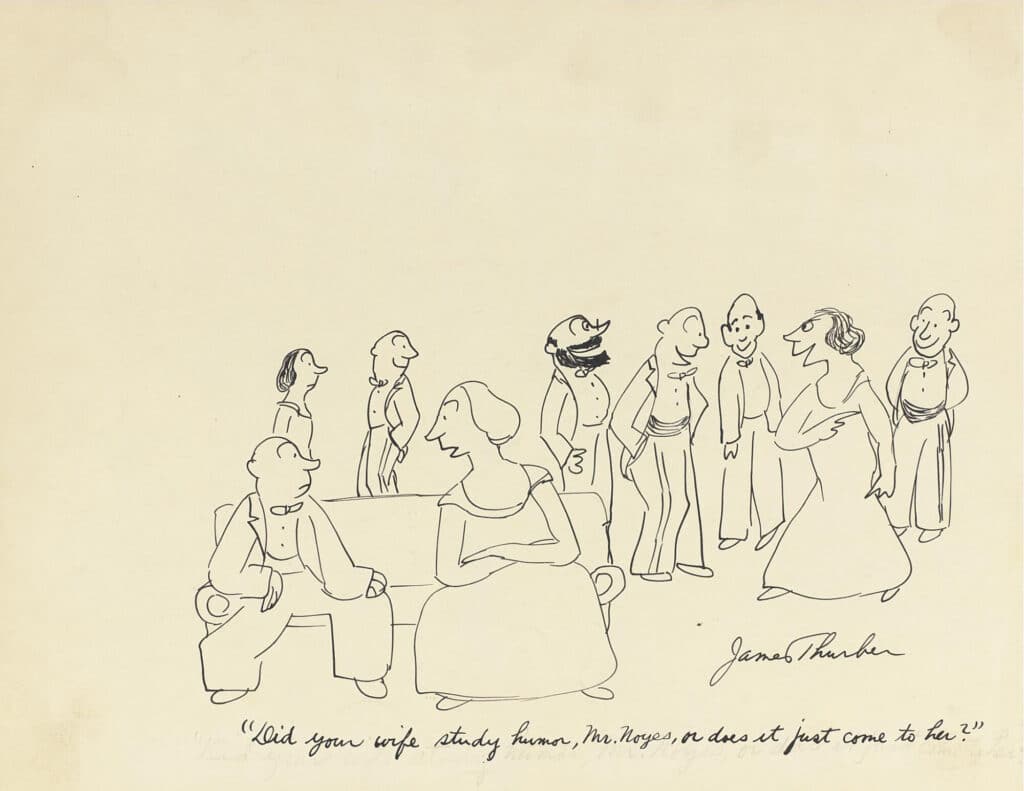

But perhaps one of the most popular New Yorker writer/illustrators who went on to make a well-known literary career from illustrative writing was James Thurber. Originally hired as Managing Editor (“Writers are a dime a dozen, Thurber,” said Ross when making the hire), Thurber was able to secure a more-desired writing position when Ross realized his mistake just five months later.

As for his loose style of illustrating, a former foe-turned-fan led the charge for his artwork to appear on the pages of The New Yorker – “It was White who fished a selection of Thurber’s doodles out of the garbage and first showed them to the magazine’s art department, and it was White who helped Thurber develop his style as a humorist,” according to a 2010 article in The New Yorker.

“I don’t think any drawing ever took me more than three minutes,” James Thurber once said of his work. His comic writings—stories, portraits, sketches, parodies, memoirs—spare no one, least of all himself.

Collecting

The New Yorker has always been collectable just as National Geographic has always been collectible. Every issue had items of interest to the reader, and presented something to read again and again to gain more and more insight into the World of New York or, in the case of National Geographic, the planet and its many wonders. Issues in good condition can sell for anywhere from $20 to into the thousands.

Original illustrative art is highly collectible. Individual stand-alone original art can be found for as low as $50 and as high as $5,000, whereas original cover art prices tend to sell for $2,000-$3,000 with the high end being $9,000-$10,000, depending upon the artist and the image and its condition.

To gather more insight into the world of The New Yorker cartoons, check out The New Yorker’s Cartoon Desk online at newyorker.com/cartoons/cartoon-desk

Editor’s Note: I encourage readers to seek out Defining New Yorker Humor by Judith Yaross Lee to be fully “in the know.”

Related posts: