Story and photos by Donald-Brian Johnson

In the world of mid-twentieth-century décor, it wasn’t enough for a designer to be a household name. What sold everything—from dinnerware to dishwashers to draperies—was exactly the right household name. That name had to be exotic, but not so exotic as to frighten away customers. It had to suggest exclusive buyer taste, without suggesting exorbitant cost. And, most importantly, it had to be unique.

To ensure that their names were firmly implanted in the minds of the buying public, many giftware designers of the 1950s and ‘60s had them boldly emblazoned on their work. No need to wonder if a fused glass platter was by Michael and Frances Higgins. The “Higgins” signature in gold said it all.

Some designers, whose given names were less than melodious, took the movie star path, rechristening themselves with names that were, like their designs, fresh, new, and previously unknown. Georges Briard, for instance, whose signed kitchen and partyware items became ubiquitous mid-century fixtures, began life as the equally mellifluous (but perhaps less ad-friendly) Jascha Brojdo.

For three popular ceramists of the period, whose careers were entwined, their names became their brand. Two opted to go the name-changing route. Sascha Brastoff originally answered to the more mundane moniker of Samuel Brostofsky. His protégé, Marc Bellaire, was known to the folks back home as Donald Fleischman. The least well-known member of the trio, however, opted to stick with the name he was given: Matthew Adams.

Sascha Brastoff: The Modern Cellini

Sascha Brastoff was his own best invention. While many giftware designers of the era have faded into oblivion, the Brastoff name endures. Certainly, his superb decorative talents, accompanied by seemingly limitless imagination, account for much of that success. But there’s another reason Brastoff remains just as popular with today’s collectors as he was with consumers of the past: his natural flair for self-promotion. Brastoff’s public persona became so intermingled with his work that it’s hard to imagine one existing without the other. “Sascha Brastoff” became a household name, encompassing both the artist and his art.

Ads of the period show the perennially youthful and photogenic Sascha ensconced among his many modernistic creations, looking just as one might imagine an artist should look — pensively musing; art pad and brushes in hand. No false modesty here: he was billed as “the man of many talents,” “the modern Cellini,” and “the internationally acclaimed designer from whose talented hands comes a galaxy of new and exciting contemporary accessories.”

8” h, $125-$150

Born in 1918, Brastoff trained briefly at Cleveland’s Western Reserve School of Art, then moved to New York. Following military service during World War II (which included stage and screen appearances in Winged Victory), his flair for theatrical design found an outlet at 20th Century Fox, where he designed costumes for, among others, Carmen Miranda. Along the way, his ongoing ceramic work attracted the attention of Winthrop Rockefeller. The philanthropist/investor became Brastoff’s patron, an association that lasted throughout the artist’s career.

The 35,000 square foot Brastoff studio in Los Angeles, which opened in 1953, became a Mecca for tourists and movie stars. An endless array of ceramic products was on view, from ashtrays and lamps to enamelware and sculptures, in such fanciful designs as Star Steed and Rooftops. Brastoff supervised all design, turning out over 400 new items yearly. His sure sense of what the public would want embraced almost every type of project. There were the practical ones, such as candelabra, cigarette boxes, vases, and ashtrays. There were purely art objects, such as wall plaques and decorative obelisks. There were even complete lines of china and earthen dinnerware.

Brastoff’s fame was so widespread that, even after ill health forced his retirement in the early 1960s, the Brastoff company continued to successfully turn out pieces in his style for ten more years. (Items with a full “Sascha Brastoff” signature were decorated by Brastoff himself. Those with only a “Sascha B.” signature, or the Brastoff name and a “rooster” stamp were products of the decorating staff.)

Although Sascha Brastoff’s mercurial creative interests led him in many directions, certain elements remain constant in his work. The presentation is always highly theatrical, and laced with whimsy. There is an ongoing use of unusual color combinations, sometimes metallic, or with metallic accents. And above all, each Brastoff piece shows his keen ability to make the extraordinary both commercially and artistically appealing.

There are artists. There are promoters. And then there was Sascha Brastoff: the best of both.

Marc Bellaire: Master of Modern Ceramics

Born in Toledo in 1925, Marc Bellaire studied at the Chicago Academy of Art and Chicago Art Institute, before moving to California in 1950, and beginning his association with early employer Brastoff. The object shapes and placement of decoration on many Bellaire pieces show the Brastoff influence. A curved-edge central image is often the focal point of a design, echoing the curved edges of the object itself, whether ashtray, bowl, or rounded platter. Bellaire also favored Brastoff’s bold, contrasting colors, and metallic accents. Themes, however, show a much greater variance: Brastoff’s images are often romanticized and ethereal. Bellaire’s fierce Jungle Dancers and blank-faced Mardi Gras celebrants are darker, more knowing, and more exotic.

12-1/4” d, $175-$200

The effect is even more pronounced and startling in the three-dimensional figurines Bellaire produced to accompany such lines as Mardi Gras and Jamaica. Here, the relationship to reality is intriguingly tenuous. While the images are clear, their details are minimal: the featureless Mardi Gras dancer’s carnival mask, or the ballooning sleeves and floppy straw hats of the Jamaica musicians. Bellaire’s ease with the other-worldly came in particularly handy for his large-scale design assignments in Hollywood, Las Vegas, and at Disneyland.

Although perhaps not for every taste, Bellaire’s strikingly original designs make his ceramics ideal accent pieces in a 1950s-modern home. Heralded by Giftware magazine as one of the top ten artware designers of the ‘50s, Marc Bellaire’s work reflects the message he conveyed to budding craftsmen: “creative expression must bring joy to its creator; without it, the work itself lacks joy.”

Matthew Adams: Depicting “The Final Frontier”

Born in 1915, Adams began his Alaskan adventures in the mid-1950s while employed by Brastoff. The studio had received a contract to produce a series of ceramics with Alaska-related images, for sale as souvenirs at a Juneau trading post. Brastoff gave the assignment to Adams, confident in his ability to fuse the somewhat rustic images, a first for the designer’s line, with the more modern “Brastoff style.”

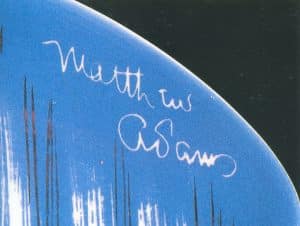

Giving Adams sole credit for the Alaska line has several strong points in its favor. When Adams left Brastoff’s employ after three years and opened his own studio, the all-Alaska work he produced was almost indistinguishable in style from the designs he had earlier created for Brastoff. Additionally, Brastoff never claimed credit for the Alaskan images or challenged Adams’ continued production of them. The majority of the Alaska pieces bear the signature “Matthew Adams,” with, at times, the addition of another word that would seem to be self-explanatory: “Alaska.”

What’s in a name? For this trio of talents, the answer is “plenty”. Thanks to their creative energies, mid-twentieth-century ceramics embarked on new artistic paths. And, thanks to their impossible-to-miss signatures, buyers knew exactly what they were getting. No second-guessing, then or now.

Donald-Brian Johnson is the co-author of numerous Schiffer books on design and collectibles, including Postwar Pop, a collection of his columns. Please address inquiries to: donaldbrian@msn.com

Photo Associate: Hank Kuhlmann

Related posts: