When it comes to evidence of historic events, broadsides – a large printed sheet of paper used to inform, proclaim, report or announce things of interest – are often viewed as such. Often used as “infomercials,” broadsides were produced to promote.

The Library of Congress houses one collection referred to as “Printed Ephemera: Three Centuries of Broadsides and Other Printed Ephemera” that includes 17,000 items that represents “some of the subject strengths and amazing diversity of the entire collection.” The teaching materials are made available for use and are filled with great information. Let’s take a quick class.

Broadsides – by far the most popular ephemeral format used throughout printed history – are single sheets of paper, printed on one side only. Often quickly and crudely produced in large numbers and distributed free in town squares, taverns, and churches or sold by chapmen for a nominal charge, broadsides are intended to have an immediate popular impact and then to be thrown away. Historically, broadsides have been used to inform the public about current news events, publicize official proclamations and government decisions, announce and record public meetings and entertainment events, advocate political and social causes, advertise products and services, and celebrate popular literary and musical efforts. Rich in detail and variety, and sometimes with striking illustrations, broadsides offer vivid insights into the daily activities and attitudes of individuals and communities that created America’s yesterdays.

Of course, broadside printing has flourished since the dawn of printing itself, the oldest dated example being a letter of indulgence printed by Gutenberg in 1454, before he printed his famous Bible. Unfortunately, there is no known extant copy of the first American broadside, “The Oath of the Free-Man” printed by Stephen Daye in Cambridge in 1639, which remains the elusive black tulip of American printing history.

Colonial printers of newspapers and almanacs often printed broadsides as a source of extra income, in addition to other jobbing work, and some printers sold books and stationery supplies as well. Essential late-breaking news was transmitted as broadside “Postscripts” or “Extras” to the weekly newspapers. Official government business and notices of meetings were disseminated by broadsides; they were used to preach morality and to demonstrate the consequences of wrongdoing; but ballads and verse were also popular and plentiful. Illustrations were difficult to design and time-consuming to cut from wood, so most printers accumulated a supply of “stock” woodcuts for repeated use. Copperplate engravings were rare until after 1800.

New vitality and visual interest were infused into the typography of early nineteenth-century ephemeral printing by Robert Thorne’s invention of Fat Face type in 1803, the first real display typeface. The introduction of steel engravings in the 1820s expanded the use of fine engraving processes in mass production. Evidence of further technological advances in printing may be traced through the collection, notably the riot of color that chromolithography brought to ephemeral printing in the last third of the nineteenth century.

The breadth of the collection makes it possible to follow political activities at the local, state, and national levels over many decades and to compare strategies and issues in different geographic areas. Executive proclamations, citizen petitions, and campaign literature are all well represented.

Major national policy changes are documented and sometimes influenced by broadside polemics. “National Utility, in Opposition to Political Controversy” marks Thomas Jefferson’s conversion from a strict agrarian philosophy by publishing his famous January 1816 letter in which he states “We must now place the manufacturer by the side of the agriculturist … manufacturers are now as necessary to our independence as to our comfort.” Jefferson’s testimony was influential in the passage of the Tariff Act of 1816, which formed the basis of American protectionism for the next thirty years. In “No Annexation of Texas” New York leaders, including Albert Gallatin and Theodore Sedgwick, encourage citizens to oppose the ratification of a treaty that would make Texas a state.

One rare broadside is even responsible for introducing a new word to our political vocabulary. In 1812 the Jeffersonian Republicans forced through the Massachusetts legislature a bill rearranging district lines to assure them an advantage in the upcoming state senatorial elections. To dramatize the extraordinary division of Essex County for partisan gain, Federal polemicists drew the map of the South District in the form of a salamander, a mythological monster shaped like a lizard. The South District was formed from a single line of towns along the outside of the county and Chelsea from Suffolk County. Although Governor Elbridge Gerry had only reluctantly signed the redistricting law spawned by zealous Republican colleagues, this caricature, “The Gerry-mander. A New Species of Monster” has forever connected his name to gerrymandering, a word that has come to describe any arbitrary redistricting for political advantage.

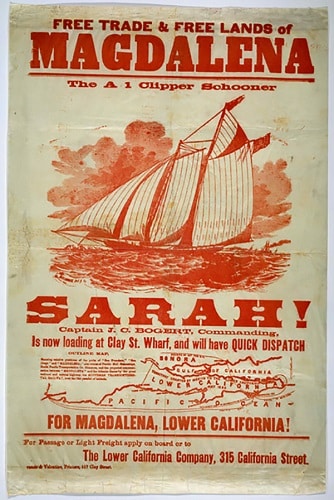

In an attractive tricolored chromolithographic circular featuring a lush rural landscape, The Burlington & Missouri River R.R. Co. offers “Millions of Acres” of Iowa and Nebraska Lands on ten-year credit. Free rooms and discount train tickets lure land-prospecting clients. And for those with a more adventurous spirit, the billowing sails of the clipper schooner Sarah, printed in bright red, beckons the immigrant-traveler to explore the “Free Trade & Free Lands of Magdalena,” Lower California. For the farmer interested in the latest in labor-saving machinery of 1875, the manufacturer of “Gale’s Patent Horse Hay Rake!” notes that it has taken the first premium at the Michigan State Fair for the past six years, is better than any other in the market, and is “so easily managed that a small Boy can run it with very little effort.”

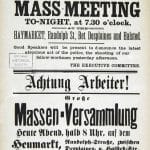

As industrialization brings many workers and immigrants to large cities, some see organized labor as a means to combating low wages, long hours, and poor working conditions. Coverage of speeches both for and against labor and calls for mass meetings of workers are frequent. The year 1886 marked the climax of the workers’ efforts in many industries throughout the country to strike for the eight-hour day. In Chicago, in the aftermath of the May first general “walk out,” several strikers were shot by police and a mass meeting was called for May 4 to protest police violence. Two versions of the 1886 handbill “Attention Workingmen!” announce this demonstration in Haymarket Square, Chicago, that led to one of the most famous labor riots in American history. More than thirty policemen were killed or wounded by a dynamite bomb. Both versions are printed in English and German, but the rare first version includes the command: “Workingmen Arm Yourselves and Appear in Full Force!” This version was used by the prosecuting attorney in the Haymarket Riot case to prove that the inflammatory writings of demonstration organizers were responsible for the violence that ensued. August Spies, editor of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, argued that as soon as he saw the first version he ordered it destroyed and prepared the second version with the inflammatory phrase deleted. Nevertheless, he and six other anarchists were sentenced to death.

An American Time Capsule: Three Centuries of Broadsides and Other Printed Ephemera presents a unique opportunity for students to examine American political and social history through analysis of a wide range of documents including broadsides, song sheets, notices, advertisements, proclamations, petitions, manifestos, ballots, and tickets to special events.

The collection provides both digital images and searchable electronic text. The items shed light on innumerable topics from the seventeenth century to the present: the Revolutionary War, slavery, the Civil War, women’s suffrage, and the emergence of the United States as a world power, to name a few. The printed material was produced as the events unfolded and offers unique snapshots of our past. The Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources program provides primary source-based staff development to teachers across the country.

Teachers and researchers are encouraged to visit: loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/connections/time-capsule to learn more about the standards met and gain access to teaching materials.

Broadsides: Insight from the Library of Congress Collection

Photos Courtesy of: Cowan’s auctions; doc.newberry.org; chmn.gmu.edu; Wikimedia.com; picryl.com; ourgame.mlblogsw.com; repository.duke.edu

The working classes of heavily-immigrant New York City had been lukewarm to the war from the start, owing to the fact that a majority of the South’s exports passed through the ports and markets of the city and therefore provided many immigrant jobs. The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863 strengthened immigrant opposition to the war as many foresaw free blacks migrating to the city in droves to compete for already low-paying jobs. The Conscription Act of 1863 was the final straw, and local Democrats and Southern sympathizers seized on the opportunity to foment rebellion against blacks, Republican supporters and newspaper offices, and eventually federal troops, resulting in the New York City draft riots, which were likened to a Confederate victory.

Printer Samuel Tousey put his presses to work immediately in order to quell the hysteria, and to remind people that their true enemy was the South and its traitors.

Although signed “A Democratic Workingman,” Tousey was in fact a committed Republican. His New York Times obituary of 1887 states that “he joined the Republican Party at its organization, and throughout the war was on terms of intimacy with many of its leaders,” and says of his appeals, that “a most wholesome effect was produced.”

Related posts: