Discovering American Indian Baskets

Baskets, big or small, plain or fancy, flat or deep, are all around us. They hold dinner rolls, houseplants, keys and mail and sewing notions, and even paperclips and office files. We use baskets in countless ways, often every day. Yet, baskets are so unassuming and familiar that we often rely on them without even thinking about them. How were they made? Where do they come from? Many baskets are entirely, or at least mostly, hand-made by real people — usually women — living somewhere around the globe.

For anyone interested specifically in American Indian baskets, the topic may seem complex. How can one tell if a basket really has been made by a Native American? If so, is it from the Southwest, Northwest Coast, Eastern Woodlands, or elsewhere? Is it old? What about its condition? Should it be repaired or restored, if needed? What is it worth?

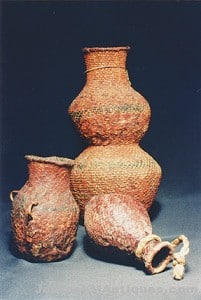

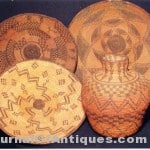

At first glance, baskets seem to come in an endless range of shapes and sizes. The anatomy of a basket provides clues to its origin and function. Both shape and size are important. (Is it a jar, tray, bowl, or other shape?) More helpful, though, is the ability to recognize basic construction methods and materials used to make and decorate a basket.

Learning how to look at baskets is important. Books, the internet, museum exhibits, and images provide resources for developing an eye for assessing baskets. Specialty shops and galleries, shows, and auction houses are also helpful. Their proprietors are knowledgeable and will share pointers. Dealers at these venues also often allow potential customers to handle baskets–to feel a basket’s texture and weight or examine its condition closely by eye or with a magnifying lens.

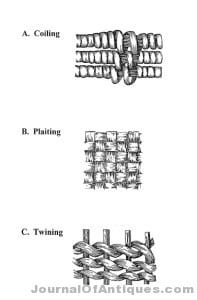

Start by determining how a basket is made. Almost all baskets are constructed in one of just three basic techniques, used singly or in combination: coiling, twining, or plaiting. Each method has its variations — like spacing stitches apart or closely packing them together — but each is identifiable with a little practice. Certain methods sometimes can be associated with particular cultural regions, specific groups, and even individual basketmakers or their families. Northwest Coast tribes, for example, may be well known for totem poles, but they also have twined splendid baskets. Basketmakers in regions like southern California and the Southwest have favored coiling. Plaiting of woodsplints has dominated Northeast basketmaking for generations.

Materials are often the most reliable clue as to where a basket was made. Native basketmakers customarily have relied on local resources in their own environments for materials. For example, a yucca-stitched coiled basket likely was made in the desert Southwest (e.g., by Tohono O’Odham, or Papago), while plaited and twined cedar bark examples usually come from the northern rain forests of the Northwest Coast.

Those who recognize the appearance of specific materials used in making baskets (like somewhat rough, dull hardwood splints versus glossy cane weavers versus thin paperlike raffia strands) are not fooled by an imported basket. For example, the technique, form, and design of a twill-plaited bamboo basketry box from the Asian-Pacific region may be confused with a similar Native American product from the Southeast U.S. But a closer look reveals differences between American Indian and non-native materials and dyes.

The ways in which baskets are decorated vary culturally and regionally. Weaving or stitching elements may be structurally manipulated during construction (e.g., twill plaiting to create a patterned weave). Dyed or extra elements (e.g., dyed splints or wool yarn wefts) can be added during construction. And additional superstructural materials (e.g., paints or pendants) can be applied or attached to a finished basket.

Preferences among Native basketmakers often result in products from certain regions or by particular makers that have a specific, recognizable “look.” A similar basket that differs in form, technique, materials, or ornamentation may be from elsewhere. It requires a second look plus further research, in addition to the pointers discussed here.

People trolling the internet, attending local auctions, or trekking through thrift stores and group shops, consignment galleries, and flea markets regularly come across baskets. More often than not, these baskets are unidentified. These venues provide a good opportunity to study a basket’s anatomy and apply the pointers mentioned above.

The most reliable sources for Indian baskets, as with any collectible, are reputable dealers and auction houses or specialized galleries. These professionals have invested time and money in learning their particular subject and generally offer authentic, good-quality examples.

Collectors are well advised to collect what they like and to buy the best they can afford. Remember to take into account the fact that baskets are three-dimensional. They rapidly take up space. So quality, not quantity, should be the operative goal. If a tempting basket isn’t quite what you want, wait until you find the one that is fully satisfying. You will be living with it, caring for it, and enjoying it for a long time. So be sure to collect what you like.

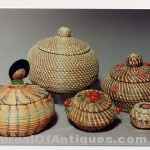

Some collectors look for Native baskets made by particular tribes (like the Pomo or Apache) or from certain regions (like southern California). Others collect only one type of basket (like Northern California women’s caps). Still others seek out only beaded coiled bowls or plaited woodsplint storage baskets. Whatever you choose, baskets should be well made and aesthetically pleasing. After all, they become part of your home decor.

The condition of a basket is important. Today’s collectors seek out baskets with minimal damage or restoration. Some “honest wear,” or evidence of genuine Native use, often does not detract much from value.

Baskets by their very nature are fragile. A basket that is faded, missing stitches, or has a rim-break may be tempting. But imperfections can greatly affect value. A “reasonably priced” imperfect basket may seem like a bargain. But damage is hard and often costly to repair. Professional conservators who are skilled in repairing baskets generally have a waiting list. Only the choicest “as is” baskets are likely to be accepted by them for repair or restoration, no matter what price one is willing or able to pay. So, an imperfect “as is” basket will likely remain exactly that—imperfect.

Besides condition, other factors affect a basket’s value and price, including a basket’s fineness of weave, its design and aesthetic appeal, possible maker, and age. In general, the finer a basket’s weave or the higher its stitch count, the presence of human or animal figures, documentation to a known or famous Native weaver, and age of more than 100 years may command a premium. But many lovely baskets in excellent condition have been fashioned more recently and are modestly priced in the current market. Some collectors prefer contemporary baskets made by accomplished Native basketmakers working today to earlier examples.

Before buying a basket, find out about it. Hold it in your hands. Look at it. Use a 5X to 10X magnifier and a blacklight (to check for repairs or restoration). Ask the dealer or the basketmaker all about the basket BEFORE you buy it. Determine whether the basket has any problems. Then, if you decide to buy it, ask for a detailed receipt to keep with the basket.

After purchasing a special basket, keep it away from direct sunlight, fluctuating heat, wood stoves, excessive humidity, or other unstable conditions. But above all, enjoy the basket. Learn more about the basket and its skillful Native maker. Doing so will expand your understanding of the remarkable complexity of the timeless Native craft-art, and you will have a lot of fun.

A survey of baskets in full color, as well as comparisons with non-Native American baskets, is provided in American Indian Baskets: Building and Caring for a Collection, by William A. Turnbaugh and Sarah Peabody Turnbaugh (2013, Schiffer Publishing). The book’s other features include nearly 800 color images, a list of American museums with significant Indian basketry collections, comprehensive bibliography, and list of internet resources.

Basket Construction

Coiling is a type of sewing in which whipstitching lashes together a spiraling foundation of one or more rods or bundled grasses.

Plaiting is a weaving technique in which warp and weft elements are woven alternately over and under each other at right angles, resulting in a checkerboard effect. Wicker plaiting uses rigid elements that are rounded instead of flat. Twill plaiting varies the intervals used to weave over and under.

Twining is a weaving method that often starts with a flat spoke-like arrangement of warp elements. They are bent upward, vertically, from the base and held together throughout with two or more horizontal weft elements (weavers) that cross each other between warp elements. Diagonal twining varies the intervals used to weave over and under.

Related posts: