By Maxine Carter-Lome, publisher

One Hundred years ago this coming February, British archaeologist and Egyptologist Howard Carter entered an undiscovered burial chamber in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings to discover what still is considered one of the greatest archaeological finds of modern times: a sarcophagus holding the mummified remains of Tutankhamun, the boy king believed to have died around 1340 BCE. Since then, the world has been fascinated with the life and death of this 18th Egyptian Dynasty king and the story of discovery that brought him back to life and captured the world’s attention.

Artifacts from King Tut’s tomb have since toured the world in several blockbuster museum shows, including the worldwide 1972-79 Treasures of Tutankhamun exhibitions. Eight million visitors in seven U.S. cities viewed the exhibition of the golden burial mask and 50 other precious items from the tomb.

Leading up to the 2023 centennial anniversary of Carter’s discovery, Tut is again out on tour with 150 burial artifacts making their way from exhibitions in London and then Sydney to their final resting place in early 2023 at the as-yet-unfinished Grand Egyptian Museum in Cairo, located near the Pyramids of Giza. Too fragile to travel outside of Egypt, Tutankhamun’s mummy remains on display within the tomb in the Valley of the Kings in the KV62 chamber, his layered coffins replaced with a climate-controlled glass box, and his golden burial mask is on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Beyond King Tut: The Immersive Experience

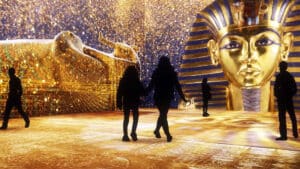

Closer to home, King Tut fans will be able to learn more about his life and times during this celebratory year through Beyond King Tut: The Immersive Experience, which had been at The National Geographic Museum in Washington, D.C. and is now headed to select cities around the country this coming year. Done in partnership with National Geographic, The Immersive Experience features 25,000 square feet of images and film that tell King Tut’s story and show what life was like in ancient Egypt in a way that brings this 3,000-year-old story to life in a state-of-the-art way.

So, who were these two men born millennia apart but now forever linked through history? And, what have we learned about both in the century that has passed since they first met?

King Tut

Although many details of Tutankhamun’s short reign remain lost to time, historians have spent years trying to piece together the pharaoh’s life and legacy since Carter’s discovery.

Born during ancient Egypt’s 18th Dynasty—which stretched from 1550 BCE to 1295 BCE—Tut began his life under a different name: Tutankhaten.

Genetic testing has verified that King Tut was the grandson of the great pharaoh Amenhotep III, and almost certainly the son of Akhenaten, a controversial figure in the history of the 18th dynasty of Egypt’s New Kingdom (c.1550-1295 B.C.).

Akhenaten upended a centuries-old religious system to favor the worship of a single deity, the sun god Aten, and moved Egypt’s religious capital from Thebes to Amarna. In honor of the new deity, he changed his own name to Akhenaten and named his son Tutankhaten, meaning “living image of Aten.”

After Akhenaten’s death, two intervening pharaohs briefly reigned before the nine-year-old prince took the throne. Tutankhamun reversed Akhenaten’s reforms early in his reign, reviving worship of the god Amun, restoring Thebes as a religious center, and changing the end of his name to reflect royal allegiance to the creator god Amun. He also worked to restore Egypt’s stature in the region; however, his true greatness as a pharaoh and his contributions to Egyptian life and culture will never be known. Tragically, Tut’s life was cut short at the age of 19.

Conspiracy theories and speculation abound when it comes to what (or who) killed Tut at such a young age but the truth, according to forensic examinations of his remains, suggests it came down to poor genetics.

According to History.com, Tut’s remains tell us he was tall but physically frail, with a crippling bone disease in his clubbed left foot. He is the only pharaoh known to have been depicted seated while engaged in physical activities like archery. Traditional inbreeding in the Egyptian royal family also likely contributed to the boy king’s poor health and early death. DNA tests published in 2010 revealed that Tutankhamun’s parents were brother and sister, and that King Tut’s wife Ankhesenamun was also his half-sister. Their only two daughters were stillborn.

Because Tutankhamun’s remains revealed a hole in the back of the skull, some historians had concluded that the young king was

assassinated, but recent tests suggest that the hole was made during mummification. CT scans in 1995 showed that the king had an

infected broken left leg, while DNA from his mummy revealed evidence of multiple malaria infections, all of which may have contributed to his early death.

After he died, Tutankhamun was mummified according to Egyptian religious tradition, which held that royal bodies should be preserved and provisioned for the afterlife. Embalmers removed his organs and wrapped him in resin-soaked bandages, a 24-pound solid gold portrait mask was placed over his head and shoulders, and he was laid in a series of nested containers – three golden coffins, a granite sarcophagus and four gilded wooden shrines, the largest of which barely fit into the tomb’s burial chamber.

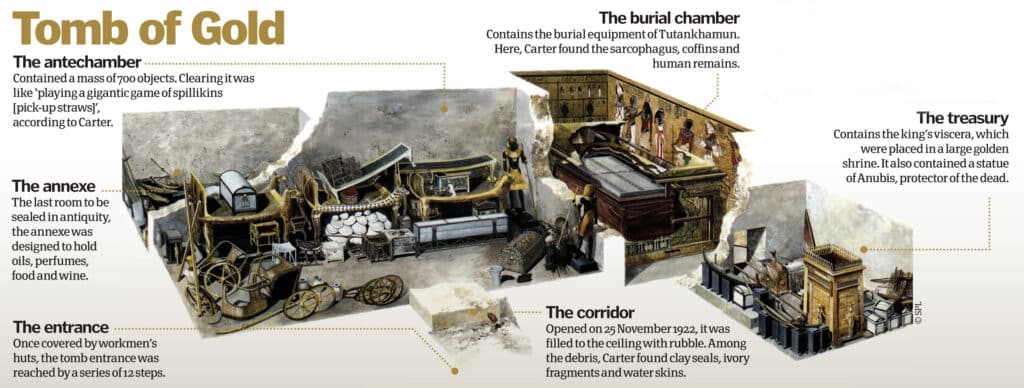

Because of his tomb’s small size, historians suggest King Tut’s death must have been unexpected and his burial rushed by Ay, who succeeded him as pharaoh. The tomb’s antechambers were packed to the ceiling with more than 5,000 artifacts, including furniture, chariots, clothes, weapons, and 130 of the lame king’s walking sticks.

The entrance corridor was apparently looted soon after the burial, but the inner rooms remained sealed. The pharaohs who followed King Tut chose to ignore his reign; despite his work restoring Amun, Tutankhamun was tainted by the connection to his father’s religious upheavals. Over the years, the tomb’s entrance became clogged with stone debris, built over by workmen’s huts, and forgotten … until February 16, 1923, when Howard Carter broke through and entered his burial chamber.

Howard Carter

By the time he discovered Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922, British archaeologist Howard Carter had been excavating Egyptian antiquities for three decades. At the time of the discovery, archaeologists believed that all the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings, across the river from ancient Thebes, had already been cleared. Carter believed otherwise and was driven to prove he was right.

Carter had been excavating in the Valley of the Kings under the patronage of George Herbert, the 5th Earl of Carnarvon (better known as the real-life Lord of the fictitious Downton Abbey home) since 1917, but by 1922 he still had not made any finds of major significance. When Lord Carnarvon threatened to withdraw his funding, Carter convinced Carnarvon to bankroll a final excavation season. The request paid off, and on November 4, 1922, Carter’s team discovered the top of a staircase. Further digging revealed a door to what would turn out to be Tutankhamun’s tomb.

Three weeks later, on the 26th, Carter smashed a hole into a stone wall in an underground hallway there. Asked if he could see anything as he aimed his flashlight into the darkness, Carter replied, “Yes, wonderful things,” according to his book The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen, written with Arthur Cruttenden Mace in 1923. In fact, so great was Carter’s find that it took eight years for all the objects in the tomb to be documented and removed.

Three months later, in February 1923, Carter entered the burial chamber to find Tut’s sarcophagus. His mummified remains, hidden from the light of day for more than 3,000 years, were about to propel this marginalized and long-forgotten king of ancient Egypt into the media spotlight and make him a household word that still draws big crowds a century later.

Hidden Treasures

In total, it is said that over 5,000 objects were eventually removed from the tomb. The trove of items from his life and for the afterlife, as well as Tut’s well-preserved body, provide Egyptologists, scientists, and historians with an unprecedented look into the young king’s life and the times in which he lived to help piece together his story. Here are just a few of the many items that help bring King Tut to life:

Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus is probably the most known and recognized artifact to come out of the burial chamber. Tut was laid to rest within three coffins nested within each other and weighing in total about 1.25 tons (1.3 metric tons). All three coffins show Tutankhamun with a long beard and holding a crook and flail. The Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities notes that the outer coffin is made of gilded wood and has blue and red glass on its crook and flail. The second coffin is also made of gilded wood and was found with several plants—including disintegrating lotus flowers—on it. The Ministry notes that the third and innermost coffin is made of solid gold and was found wrapped in linen. Tutankhamun was laid to rest in this innermost coffin, with his death mask among other items on him.

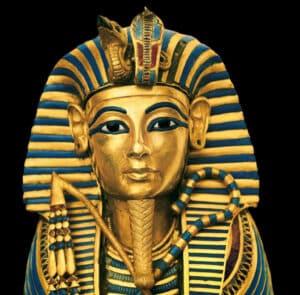

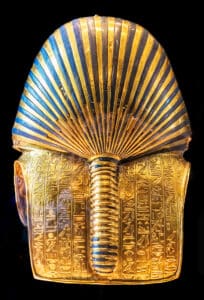

Tutankhamun’s gold death mask, created in the likeness of the deceased to help their souls recognize their own bodies and return to them, provides us with another likeness of the boy king. Placed on Tut’s face, the 21-inch-long (53 centimeters) ornate mask was manufactured mainly from gold inlaid with semiprecious stones and colored glass paste and weighs a whopping 22 pounds (10 kilograms). The mask depicts Tutankhamun with a long beard and a headdress bearing a cobra and a vulture. On the back of the death mask is a spell from the Book of the Dead, written in hieroglyphs, which “guaranteed the mask’s ability to function as the face of the deceased.” The third innermost coffin that Tutankhamun was buried in has the same spell written on it.

Tutankhamun was buried with two daggers – one with an iron blade placed by his right thigh and one with a gold blade placed above his abdomen. Both daggers were found wrapped in different layers of the pharaoh’s mummy bandages. The iron used in the dagger was out of this world, crafted from a meteorite, with a pommel made of rock crystal. Both daggers have a gold handle with intricately carved patterns. Both daggers show signs of wear, although it is not certain whether either dagger was ever used in a hunt or some other activity.

At least four board games were found in Tutankhamun’s tomb. Some of the boards and game pieces found in the tomb were made of ivory, and the boards seem designed for the “game of twenty” and “senet.” Neither game’s rules are entirely clear. The Grand Egyptian Museum notes that senet was played with a board of 30 squares and the goal “was to safely navigate all the pieces off the board while preventing the opponent from doing the same.” The “game of twenty” rules are also uncertain. Among scholars who have studied the game, “it is generally assumed that the two players started on each of the opposite sides of the board” and that “they then moved their pieces down the central aisle toward the final field and off the board to win the game.”

One of the lesser-known treasures from Tutankhamun’s tomb is a mannequin used to help choose, adjust, and store the king’s wardrobe and jewelry. Tut was a very snappy dresser with a huge wardrobe, both for his life and afterlife.

Carter uncovered hundreds of garments – 12 sumptuous robes, dozens of sandals, underwear, socks, and even Tut’s baby clothes.

Related posts: