By Maxine Carter-Lome, publisher

Fifty years ago this past April 3, 2023, Motorola engineer Martin (Marty) Cooper placed a phone call on a street in downtown New York City to his competitor at Bell Labs on what was then the world’s first cellular hand-held portable telephone. It would be over a decade before Cooper’s working prototype was commercially available but even then, the idea of a phone extending beyond the phone cord and an outlet was outside the imagination of most. Now, 50 years later, we would find it almost impossible to live without our cellphone and almost everyone we know has one. It’s stunning to consider that within a generation this late 20th-century technology based on Alexander Graham Bell’s 19th-century invention of the telephone has forever changed, like its predecessor, how we communicate as a society.

1982 B.C. (Before Cellular)

In 1982, I left my job in retail advertising to work for a trade association in Washington, D.C. that represented the Radio Common Carrier industry. At that time, Radio Common Carriers were FCC-licensed providers of land mobile radio services. The trade association, Telocator Network of America, also represented the network providers and equipment manufacturers of paging services and “beepers” as they were then called. My first day on the job as Telocator’s new advertising and trade show manager was at an industry convention where Motorola unveiled its alphanumeric pager that allowed users to receive and send a message through a digital network. Their technology turned the popular beeper from a one-way notification device mostly associated with doctors into the first generation of text messaging as we know it today.

During my tenure at Telocator, two other significant changes took place that have forever altered the communications landscape: AT&T Corp. agreed to split up its “Ma Bell” nationwide telephone monopoly to be replaced by seven independent Regional Bell Operating Companies (“Baby Bells”), and the FCC began awarding licenses in the Top 30 major metropolitan markets in the country for a new mobile telephone service based on Bell Lab’s cellular technology. Two licenses were to be awarded in each market: one to an independent “telephone” company such as a Baby Bell and the other to a Radio Common Carrier or non-telephone entity. That put Telocator in the early 1980s at the center of the telecom universe, representing and lobbying for the paging/messaging, mobile communications, and cellular telephone industries.

The products and services being introduced by Telocator members allowed corporations, mobile workers, and business professionals for the first time to stay connected and communicate even when in their cars.

On October 13, 1983, the company named Ameritech Mobile Communications (now AT&T) turned on the first commercial cellular network in the United States in Chicago, Illinois. At the time, little hope was held that the return would be worth the investment. The general consensus among all but a few was that—given the cost of the phone and the cost of service—it would be 10 years before the market reached one million subscribers. With Los Angeles coming online less than one year later, that prediction was broken at the end of year two.

By the spring of 1984, the cellular telephone industry was set to turn on in additional major cities across the country, and new consumer cellular phone products backed by Madison Avenue advertising and Bell operating company capital started flooding the market. The appeal was simple: why spend downtime in your car when you could use that time to work? Even at $4,000, an investment in a car telephone would practically pay for itself in added productivity! That message totally resonated with commuters and mobile workers in and around big cities who spent hours a day stuck in traffic or out in the field. More than just a productivity tool, cellular phones were also becoming a new status symbol, with the pigtail antenna on a rear window of a car visual confirmation of one’s wealth and success. It was not long before everyone knew what a car telephone was, even if they still could not afford one.

The World’s First Cellular Telephone

Despite being invented in America by engineers at Bell Labs, initial concerns about cellular’s true potential kept most American manufacturers, with the exception of Motorola, out of the consumer cellular phone business in the early days, thereby opening the door for many Japanese technology manufacturers to enter the U.S. market on the ground floor. One such company was OKI Electronics, known in the U.S. at that time for their OkiData office printers.

OKI secured equipment contracts with six out of the seven Baby Bells to private label their cellular telephones early on after they manufactured what is considered to be the world’s first cellular car telephone for the original Chicago cellular service trial in 1978. To support the emerging American market and their Bell Operating Co. customers, OKI established a completely robotic assembly plant in Norcross, Georgia, and hired an all-American sales and marketing team to work directly with their new carrier customers. I joined that team in May of 1984 as the advertising and public relations manager and moved to the new OKI America corporate offices in Hackensack, NJ.

OKI’s first generation commercial cellular telephone, the CDL 200 series, was comprised of a battery and transceiver-receiver in the trunk of the vehicle with a total weight of around 86 pounds; a handset installed by the driver’s seat that was attached by a coil to a handset cradle; and a “pigtail” antenna installed on the roof or rear window.

Cutting the Cord

with carrying case.

When a new technology catches on, consumer demand becomes the accelerant that drives new product development. Bringing basic phone functionality into a mobile vehicle was one thing, but what if you could take the phone with you when you left the vehicle and continue to make and receive calls?

Deeply invested and entrenched in the cellular marketplace, both Motorola and OKI embarked on a race in the second half of the 1980s to turn the car telephone completely portable. Here, Motorola had the competitive edge thanks to Marty Cooper’s vision and work on the DynaTAC handheld portable cellular telephone.

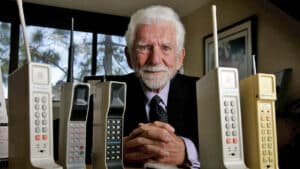

The Father of Cellular

Widely regarded as the father of the cellular phone, Marty Cooper joined Motorola in 1954. While at Motorola, Cooper worked on many projects involving wireless communications, such as the first radio-controlled traffic-light system, which he patented in 1960, and the first handheld police radios, which were introduced in 1967, but Motorola’s core business in these early years was in the manufacturing of land mobile radio equipment for public safety agencies and mobile telephones for cellular’s precursors, Mobile Telephone Service (MTS), and Improved Mobile Telephone Service (IMTS).

Given that these technologies were products of Bell Labs and that AT&T had a monopoly on all “telephone technologies” at the time, this put manufacturers such as Motorola at a disadvantage when selling into the market. As the FCC turned its sites in the mid-1970s on licensing a more advanced form of mobile phone service based on AT&T’s new cellular architecture, Motorola feared the end of its mobile business if AT&T got a monopoly on both the network equipment and phones. Motorola’s founder Paul Galvin placed Cooper in charge of their cellular telephone division with an urgent mandate to design and engineer for the future of this new wireless technology in a marketplace Motorola was intent on dominating.

While the focus among equipment and phone manufacturers in those early days was on delivering a better, scalable network service and manufacturing practical and relatable devices that could make and receive telephone calls in a car, Cooper conceived the next generation of a mobile phone as something that could fit in the palm of your hand for truly portable communications. Ten years after he made the first cellular call on his prototype DynaTAC portable phone on the streets of New York City, Cooper’s DynaTAC 8000X received FCC approval on September 21, 1983, as the world’s first commercial handheld, portable cellular telephone. This clunky “portable” phone, dubbed “The Brick” weighed 2.4 lb (1.1 kg), measured 9.1 x 5.1 x 1.8 in (23 x 13 x 4.5 cm), offered a talk time of just 30 minutes, required 10 hours to recharge, and was priced at $3,995 (roughly $10,000 in today’s dollars). It was revolutionary in concept and design but had a few generations and iterations to go before cost, functionality, and battery life made the Motorola DynaTAC affordable and practical.

Portability weighs into the mix

It was not long before more manufacturers, many from overseas, entered the U.S. market with products designed for portable mobility. Companies such as OKI, Nokia, NEC, Siemens, and Samsung all tried their hand at making “portable” cellular phones for an exploding U.S. market excited about true mobility and the ubiquitous potential of a new, nationwide wireless telephone service.

In 1985, OKI introduced a “briefcase” phone which weighed 28 pounds and consisted of a 26-pound 12v Nicad battery built inside a leatherette briefcase with a sleeve that held the handset and included a retractable antenna. When we took this revolutionary phone on press tours, our PR agency suggested I be the one to carry it into the meetings to diffuse the argument that it weighed too much to be practical. Less than two years later, OKI introduced a more practical, portable phone: the “bag” phone. Weighing in at less than 10 pounds, the bag phone consisted of a battery, receiver, and handset stacked inside a pouch the size and shape of a man’s shaving kit. While both phones were “portable” in that they could be used inside and out of the car, they both consisted of handsets that were still tethered to the battery and transceiver by a phone cord. Consumers were now ready to cut that cord – a day Martin (Marty) Cooper had been dreaming about for decades.

After leaving OKI in 1987, I spent another 17 years in the cellular telephone industry, including four as editor of three leading cellular and wireless trade magazines. During that period, I covered the rise of wireless data, the physical downsizing of phones, advances in battery technology, the transition from analog to digital phone service, the latest features and capabilities, market factors driving down the cost of phones and phone service, and the social impact of anywhere-anytime communications on how we live, work, play, and stay connected.

Today, I am as clueless as most as to what my phone can actually do but no less slavishly devoted to the ideal of personal communication.

So, What’s an Old Phone Worth?

Over the last 40 years since commercial start-up, hundreds of iterations and generations of cellular phones have come and gone, leaving behind artifacts of the technology’s product evolution for collectors to tell their own stories.

While the impulse when upgrading is to discard or put away obsolete equipment, there is a growing online resale market for old phones, with early DynaTACs going for, on average, $2,000.

It is, however, hard to say what their future value will be but if recent prices for first-generation Macintosh computers and iPhones are any indication, technology could be your next hot collectible!

To learn more about the history of cellular telephones and Marty Cooper on the 50th anniversary of the first cellular telephone call, check out these videos available to view at our online Video Gallery.

Related posts: