Story & Photos by Donald-Brian Johnson

Editor’s Note: During the infancy of Hollywood Glamour photography, the studios wanted their audience to believe that their stars were born. But in reality, they were “made” – molded, refined, packaged – by the studios that held their contract. Creating a star’s image involved producers, directors, make-up men, and hair stylists; a crucial participant, however, were the portrait photographers such as Clarence Sinclair Bull, George Hurrell, Ruth Harriet Louise, and Robert Richee - craftsmen-artists who helped create the screen images of stars and, in the process, created a glamorous form of photographic art. Here, Donald-Brian Johnson explores how the studios positioned their picture-perfect stars for maximum exposure while selling select products and promoting their films.

With the blessing (and active nudging) of their studios, the performers would soon appear in print ads promoting Max’s latest cosmetics. Not so coincidentally, those ads would also promote the studios’ latest movie releases.

Of course, the stars would need to be compensated. So what sounds fair? Millions? Thousands? Hundreds?

Nope. The “Max Factor Girls,” as they came to be known, each received annual compensation in the heady amount of … one dollar.

That’s right. One dollar. And the starry ladies who contracted with Mr. Factor were happy to have it. Over the years, Max Factor’s movieland roster came to encompass a significant slice of Hollywood history. There were silent screen sirens Clara Bow and Pola Negri … legendary beauties Loretta Young, Elizabeth Taylor, and Lana Turner … drama divas Bette Davis and Joan Crawford … and such unlikely glamour gals as TV’s “Lucy,” Lucille Ball. (She signed her first Max Factor contract in 1935, and even insisted on the services of the salon’s “Director of Beauty,” Hal King, for her divorce court appearance vs. Desi Arnaz.)

A Star Is Born

Now, free publicity is nice … but really. Signing over promotional rights to your image for just a dollar? These days, when you hear major stars doing TV voice-overs, you can be sure they’ve raked in hundreds of thousands of dollars just for lending their voices to commercials. When current top performers do appear onscreen in an ad, it’s almost

always aired overseas, where it won’t tarnish domestic acting reputations, and where the payday is even higher.

No dollar deals here. So why were the stars of Hollywood’s Golden Age so acquiescent?

Every evening on the silver screen, movies offered up new faces for public consumption. Glamour photo magazine ads like Max Factor’s made sure those new faces had a chance to register with fans, while at the same time making sure that familiar faces weren’t forgotten. Whether old pro or newbie, the most important thing was keeping your face fresh in moviegoers’ minds. And that’s where the magazine ads came in: as a dynamic return on a dollar’s investment.

Shine Like The Stars

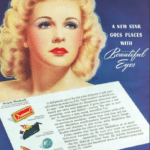

Like Mr. Factor’s, other early star-themed ads zeroed in on the most logical movie tie-in of all: beauty products. The stars shone brightly for an entire cosmetic counter’s worth of glamour goodies. Among the favorites: Woodbury Cold Cream & Powder (Dorothy Lamour, Veronica Lake, Gloria De Haven); Lux Soap (Judy Garland, June Allyson, Marlene Dietrich, Loretta Young); Jergens Lotion (Gloria Swanson); Lustre Crème (Ava Gardner); Drene (Virginia Mayo), and Maybelline (starlets Marjorie Woodworth and Elyse Knox). During the nylon-deprived World War II years, stars and sponsors even teamed up to do their bit for Uncle Sam. Barbara Stanwyck, on behalf of Armand Leg Make-Up, opined “it’s patriotic to save your hosiery.” (Barbara, noted the ad, was “now appearing in Lady of Burlesque,” where those made-up legs were presumably displayed in all their glory.)

Of course, the majority of Hollywood stars, even dressed in gunny sacks, faces scrubbed with laundry soap, would still leave onlookers gobsmacked by their natural beauty. This was never mentioned in the ads. Instead, the message conveyed was simple and to the point: use Max Factor (or Woodbury, or Lux), and you could be just as lovely and irresistible as Lana or Loretta.

Spokes-stars, (or, at any rate, the copywriters putting the words in their mouths), made sure that message came through loud and clear. The trick was in avoiding the hard sell. “Stars”, as the term implies, existed in another realm. Keeping them secure on their pedestals-yet down-to-earth enough to believably hawk everyday products-had advertisers walking a continual tightrope. Here’s a soapy (yet subtle) sampling, courtesy of Lux:

• Loretta Young: “We women know how important day-to-day care is in order to look and keep looking our prettiest. It’s 1 part beauty, and 9 parts beauty care. Lux really makes skin lovelier.”

• Marlene Dietrich: “Romance and lovely skin just seem to go together. It’s romance-love-that any woman really wants. No wonder 9 out of 10 screen stars use Lux.”

• June Allyson: “I’m a Lux girl … and Lux girls are lovelier.”

Once advertisers saw how favorably consumers responded to movie stars hustling beauty products, the race was on, as other sponsors competed for Hollywood placement. Huffing and puffing their way to the top of the heap: those relics of another time, cigarette ads.

While beauty ads were often black-and-white, cigarette advertising took a flashier approach: full-color back-cover promos in such general circulation publications as Look and Photoplay. The primary intent: persuading buyers just how inoffensive a particular brand could be. “Mild,” “cool,” and “soothing” were popular adjectives. Exotic Dolores Del Rio, appearing on behalf of Lucky Strike, was touted as having her “throat insured for fifty thousand dollars.” Said Dolores, “I take no chance on an irritated throat, and always find Luckys gentle.”

Most of the big names, however, were lighting up for Chesterfield. Among them: Deborah Kerr, Richard Widmark, and, in a bizarre World War II Christmas ad, an army-helmeted Santa Claus. All the cast members of 1948’s The Paradine Case, from ingénue Valli, to curmudgeoness Ethel Barrymore, were posed with Chesterfields in hand. Bing Crosby, pulling a new carton out of his desk drawer, noted, “There’s no friend like an old friend-and that how I feel about Chesterfields.”

Starstruck

The floodgates were now open wide. Jolene Shoes joined forces with bandleader/ caricaturist Xavier Cugat for ads featuring his drawings, and a revolving door of fetching film stars. Art Linkletter pitched vegetables for Green Giant, Abbott and Costello touted Tums, and Ozzie & Harriet shooed away germs with Listerine. Puppeteer Señor Wences drank in the joys of Seagram’s 7, while bandleader Lawrence Welk raised his baton in salute of the 1957 Dodge.

Some stars appeared in ads promoting their program sponsors. Bob “Pepsodent” Hope eventually moved on from toothpaste, ballyhooing everything from RCA Color TVs to Jolly Time Popcorn. Alfred Hitchcock balefully boosted Bufferin. Hearty vocalist Kate Smith sang the praises of baking with Swan’s Down Cake Flour (“that girl,” whispered one co-worker, “has a real sweet tusk.”)

There were oddities, as well. Maybelline Eye Makeup billed Marjorie Woodworth as “a new star with beautiful eyes who’s going places.” Marjorie never got much further than starlet status though, despite appearing in ad after ad for product after product. Still, she always looked gorgeous, whether pitching Maybelline or Royal Crown Cola. The Dionne Quintuplets appeared on behalf of Karo Syrup, complete with a testimonial from their physician, Dr. Dafoe: “Karo is the only syrup served to the Quints.” Silent movie queen Gloria Swanson had perhaps the most dismal movie ad career, appearing in a Doublemint Gum promotion, wearing a “Doublemint Dress” designed by famed couturiere Valentina (yes, the dress color matched the gum wrapper). Later, Gloria endured further-although undoubtedly well-paid-humiliation, appearing in a Jergens Lotion ad under the headline “Will you look as lovely as Gloria Swanson on her 52nd birthday?” (If you used Jergens, the answer to lovely looks at the ripe old age of 52 was evidently a resounding “yes.”)

Sometimes, a twist of fate led to star product promotion. In the 1950s, screen queen Joan Crawford embarked on her fourth marriage, this time to Pepsi-Cola CEO Alfred Steele. Accompanying him on his business travels worldwide, Crawford became the unofficial “face” of Pepsi, appearing in numerous news stories and feature articles clutching a bottle of her favorite beverage. That endorsement extended to Joan’s movie sets: when Crawford was in residence, pop machines were only permitted to carry Pepsi products, much to the dismay of any Coke-loving costars.

With the advent of television in the late 1940s, star presence in magazine ads began to lose its luster. By the mid-1950s, most of the stars “selling it” were doing so on TV, often on their own programs, and for much more than the symbolic Max Factor dollar. Star-themed print ads eventually became the last bastion of once-familiar faces, trading in on past glories.

Fortunately, vintage star ads are still readily available to today’s collectors. They appeared in mass-market publications, and stacks of those ad-laden magazines, carefully saved by the original subscribers, can often be found at estate and garage sales. It’s an affordable hobby: complete magazine prices run in the $5-15 range, topping out at $25. If you’re interested only in a single star, and lack the time (or patience) to peruse piles of old magazines, buying a ready-to-go ad is a logical, if more costly, option. Enterprising dealers in paper goods buy up old magazines and dissect them, selling ads featuring specific performers at $5-10. The ads can then be individually framed, or used to create a montage. Many collectors, however, prefer to acquire complete, undamaged magazines, and keep them in their intact condition.

Paging through a magazine of the past is like opening a compact time capsule of mid-twentieth century popular culture – so don’t rush. Let’s riffle through an issue of Woman’s Home Companion from 1936. On our way to the “star ads,” we’ll find ourselves happily waylaid by a wealth of recipes, decorating tips, short stories, and news of the day. And then, that first ad appears. It’s for Chase & Sanborn Coffee, sponsors of the hit radio program, Major Bowes’ Original Amateur Hour. There’s the Major himself, and all his newly-discovered stars, including a vocal quartet, the “Hoboken Four.” Wait a minute … who’s that in the spotlight? Why, it’s the group’s lead crooner: skinny, smiling, and soon-to-be-famous Frank Sinatra!

In the words of Woodbury Powder, that’s what we call “a bit of stardust magic … a flawless, film-star finish.”

Donald-Brian Johnson is the co-author of numerous Schiffer books on design and collectibles, including Postwar Pop, a collection of his columns. Please address inquiries to: donaldbrian@msn.com.

Related posts: