By Judy Weaver Gonyeau, managing editor

Patents, blueprints, scientific diagrams, and curious drawings reveal inventions and discoveries coming into its own art form in offices, businesses, and homes. Collectors are growing like a bar chart in a bull market.

Industrial Chic. Two words that at one time would have been considered an oxymoron by trendy designers are now considered one of the trendiest “types” of decor. Another term could be Technical Art. This style of art is coming out of the filing cabinets, the archives of industry, and scientific tomes into a frame then placed on a wall where everyone can see it.

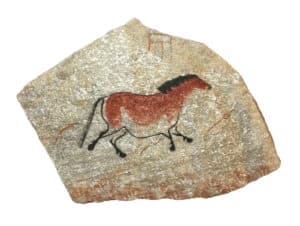

Stone Age Curiosity

For what seems like forever, human curiosity has spawned scientific curiosity. Early humans looked to communicate ideas and information and used art to present it.

The earliest paintings or drawings of man’s surroundings depicted animals, early tools, war and warriors, death, and life. They are surprisingly sophisticated and naturally fragile. The Lascaux Stone Age cave paintings in southwest France have been replicated twice to protect the originals from deteriorating. According to DW Global Media Forum, “Many generations of artists were at work in the cave, and paintings and engravings were created on top of older ones, which is difficult for non-experts to make out. In the Lascaux workshop, individual artworks are projected onto a screen in chronological order. In the pedagogical portion of the Lascaus 4 center, the various layers of paintings are separated and the details are made visible thanks to modern technology.”

This link between the discovery of the use of minerals to create cave paintings and the ability to break apart layers of illustrations from thousands of years ago all come from curiosity – to document and draw depictions of nature, and to have the technology to see within them. While obtaining an original cave drawing may not be a possibility, a print from a photograph or from the recreated artwork can be brought home to satisfy your curiosity regarding cave art, printing, or both.

Bringing Wonders to the Page

Throughout human history, sharing information has always been accompanied by images. The evolution of scientific illustration as a teaching tool became much more intricate as man turned to him/herself in body, mind, and spirit. The human experience was turning to science to make sense of all three. Prior to this focus, scientific illustration was considered to have little understanding when it came to its use, rendering much of it unnecessary. Beauty was defined as what was found in nature and in human emotion and devotion to God. Scientific illustration was mostly ignored through to the 1400s when observations of life were brought to the forefront through theology or pervasive philosophy.

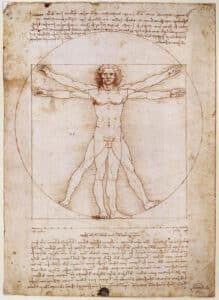

Perhaps one of the most influential and famous artists to bring this to light was Leonardo Da Vinci. Many knew him as either an artist or a scientist. He was truly devoted to sharing the beauty and study of the human body while surrounding himself with logic and forward-thinking technology at the same time. This is the man who painted the Mona Lisa and the Last Supper while conceiving things like a triple barrel canon and the precursor to the helicopter.

Da Vinci would also take his observations from working in fine art and bring them into his scientific illustrations and vice versa. Perhaps the most popular of this combining of art and science is the drawing he made called Vitruvian Man done in c. 1490. This work is a unique synthesis of artistic and scientific ideals and was often considered an archetypal representation of the High Renaissance.

This drawing represents Leonardo’s conception of ideal body proportions. You can multiply the size of the head seven times to reach the size of the body’s overall height. The measurement from the tip of the middle finger on one hand outstretched to the matching finger on the other side will also give you the height of the body. You can see the proportion of height divided into four sections – to the knee, the hip, the chest, and then the top of the head. The length from shoulder to shoulder equals the measurement from the shoulder to the wrist. This proportionate figure is used by artists to this day when working on a figure drawing or portrait painting. The size of the hand equals the size of the chin to the top of the hairline.

You can find the image of the Vitruvian Man just about anywhere as part of an art collection or as a reference image in an art studio. You can also see da Vinci’s detailed drawings of his many inventions wherever his genius inspires work and thought, from lobbies of tech companies to a mechanic’s garage. They have been seen in CAD operators’ workspaces and architects’ offices as representative of the precursors to their own work.

But da Vinci’s take on illustration is perhaps best described by the Museum of Science in Boston, “While Leonardo da Vinci is best known as an artist, his work as a scientist and inventor makes him a true Renaissance man. He serves as a role model in applying the scientific method to every aspect of life, including art and music. … His keen eye and quick mind led him to make important scientific discoveries, yet he never published his ideas. … Leonardo bridged the gap between unscientific medieval methods and the rigorous scientific methodology we use today.”

The Progression of Detail

In a published paper titled The Evolution and Influence of Art in Scientific Illustration by Ahsiya Zurita of Bard College in 2016, the author notes that, “The more scientific knowledge gained by the general public and scientific community, the more relevant illustration became. … scientific illustration is defined by the use of scientifically informed observation to create an accurate depiction of the object or subject. It is defined by the ability to illustrate the hard-to-observe phenomena, or by its abilities to present structures and details with clarity as a description of a subject. Illustrations become more accurate and scientific with the increased interest in observation as a learning tool within the Renaissance [14th-16th centuries].”

Rembrandt was next up as the artist/scientist/instructor genius who advanced scientific illustration to another level. As noted in the May 2019 issue of the Journal, the article “Medical Art” mentions the painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicholas Tulip (1632) as a representation of Rembrandt’s keen ability to observe even the finest of details. He painted the details of the hand from life after the operation was over. This artistic scientific painting showcased the abilities of the artist as science instructor illustrator.

Duplicating Efforts

Today, you can gather innumerable prints of da Vinci’s and Rembrandt’s and other early artists’ works from centuries past, but during those times sharing illustrative information was harder than discovering a painting in a cave.

Early printing of materials was intense and expensive. Woodblock printing arrived in the 9th century. The Gutenberg Press almost single-handedly made the production of the printed page easier than ever when it was created around 1436, using a screw-type wine press to squeeze down on inked metal type. According to History.com, Gutenberg’s “greatest accomplishment was the first print run of the Bible in Latin, which took three years to print around 200 copies, a miraculously speedy achievement in the day of hand-copied manuscripts.”

The modern age of printing was unleashed. By 1500, printing presses were scattered throughout Western Europe, producing more than twenty million volumes. Scientific illustration was more in demand than ever before as the thirst for more detailed information about our insides became more fascinating.

As a result of this growing interest, finding a cadaver became more difficult. Doctors would agree to pay funeral expenses if they could explore the body of someone recently passed who was not particularly rich. Large tomes regarding the anatomy of man (much more frequently than woman) became staples in medical schools and anywhere one sought higher learning. And the growth in the printing industry continued to evolve.

By the mid-18th century, the various iterations of the printing press were known to “steal jobs” from workers. The highly-trained artisans who would hand-copy and illuminate manuscripts became victims of progress by the late 15th century, but the printing industry had never been larger.

Welcome to the Patent Office

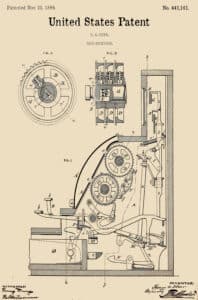

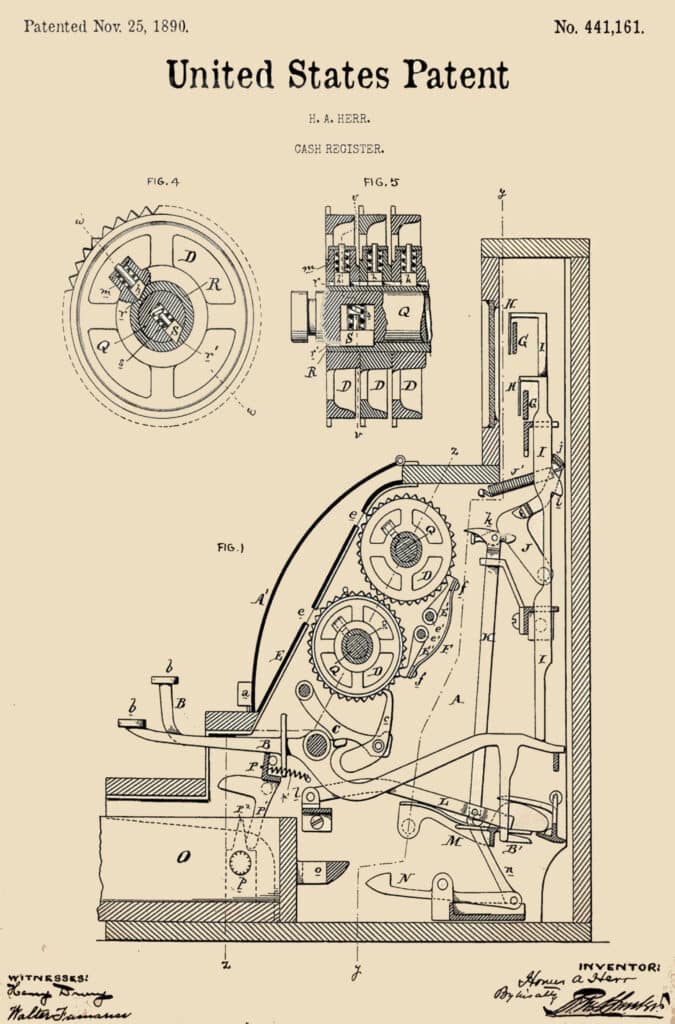

The value of information and ideas reached a new level with the opening of the U.S. Patent and Trade Office in 1790. Through the submission of an invention supported by scientific data, purpose, and who was in the room when the invention took place, a specific new item or technology could be “owned.” At that time, each patent was required to have an accompanying illustration depicting the applicant’s invention. Typically, these drawings were simplistic line drawings with no aestetic value whatsoever.

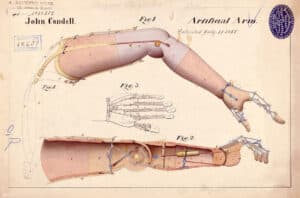

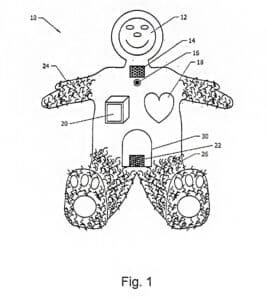

From the 1800s through the mid-20th century, more artistic flair was used with techniques including shading and showed the invention from different perspectives. Whereas some believed the drawings would become better over time, today’s examples are hardly anything to rave about for their accuracy and detail. For example, the patent illustration for an artificial arm from 1865 vs. a “Domestic Animal Telephone” from 2011:

“Up until 1880, inventors had to include an actual model of their invention along with a drawing, so many of the drawings included in patent applications were actually depictions of the draftsman’s model. With so much time committed to creating a working model of the invention, it’s no wonder that patent draftsmen would want to spend a good amount of time making sure the drawing matched. The artificial arm drawn in this patent illustration has depth, as a 3D model does, and goes into great detail in its cross-section. With all three perspectives of the arm, including the detailed drawing of the hand, the draftsman accomplished much more than what the USPTO required in a drawing.”

As for the phone, “The smiling face, the shapes strewn across the body, and the limited arm and leg hair make for a frightening drawing. This is the toy of nightmares. In reality, however, the patent drawing is meant to depict a telephone made for animals. Yet in its current state, it’s hard to imagine that an animal would even come close to this strange contraption” (illustration descriptions taken from wired.com).

Collecting Scientific Illustration

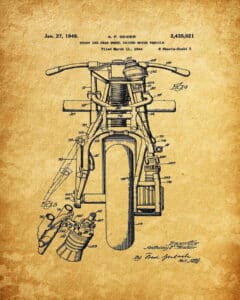

If you collect it, there is an illustration for it. Getting the patent illustration for an item is something that makers of fine prints and posters seek out to reproduce for collectors. If you like Indian motorcycles just type in “patent image for Indian motorcycle” and you will discover page after page of various model patent images. You can see the same image on parchment, colorized to look like a blueprint or a piece of art with artistic elements strewn across the sheet.

Buying original patent drawings can be a tough search, but you may have better luck by defining your search with a patent name or number, looking online at a history of a company, by the inventor’s name, or by searching patents by using www.worldwide.espatenet.com where you can type in “Teapot” and sort results from oldest patent to newest (the oldest being from 1858 in this search).

Fair Warning: once you start searching the patents and discovering the illustrations, look out – you will surely spend hours glued to your computer screen.

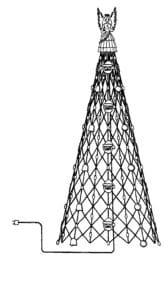

Another interesting website is www.patentauction.com where you can purchase patents and use them to license the idea and, if included, the image. Patent US D498,171 S is for a decorative light string. This particular light string has a festive Christmas theme.

In use, these images and more can contribute to the theme of your decor. Enjoy florals? An Audubon folio hand-colored image of hibiscus may work on your walls. Work from home for an electrical company? Seek out a schematic of an old radio or circuit. Drafting? A blueprint of the Empire State Building would be an impressive statement piece.

Museums also feature fine collections of illustration as it relates to a particular division of science and technology. The Met’s Department of Drawings and Prints is comprised of approximately 21,000 drawings, 1.2 million prints, and 12,000 illustrated books from the year 1400 to today. There is a Study Room for Drawings and Prints where unexhibited works can be explored, and over 177,000 works can be explored on The Met’s online database.

The possibilities are endless.

Related posts: