By Charles Worman

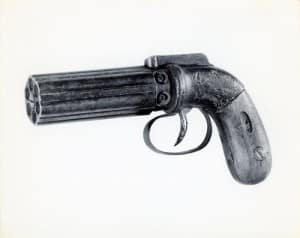

If one were to prepare a short list of those distinctly American firearms of pre-1900 vintage which have iconic status, you would almost certainly find the Pennsylvania long rifle, Henry Deringer’s pocket pistol, Samuel Colt’s revolver, Christian Sharps’ breech loading rifle, Smith & Wesson’s metallic cartridge revolver, and the Winchester repeating rifle. One other merits consideration and that is the pepperbox revolving pistol, particularly those produced by Ethan Allen (no relation to the Vermont Revolutionary War hero of the same name). Although precise definitions sometimes vary, a convenient description of a pepperbox is a handgun with three or more barrels rotating about a central axis. Such weapons of European origin existed as early as the 17th century, but the barrel cluster was rotated by hand. The term, which really didn’t come into common use until around 1850, probably was derived from a pepper shaker with its numerous holes in its top.

Samuel Colt in 1836 had been granted a U. S. patent for a single action percussion (“cap and ball”) revolver with a single barrel and a multi-chambered cylinder which rotated as the hammer was cocked manually. Ethan Allen a year later had received a patent on a double action mechanism which he applied to single shot pocket pistols. A single pull on the trigger cocked the hammer and then released it to strike the percussion cap, firing the pistol. When Allen in 1838 applied this system to a multi-barrel pepperbox, he introduced the first American double action revolving pistol. Now a long trigger pull cocked the hammer, rotated the barrel cluster, and then released the hammer. Allen pepperboxes soon caught the public’s attention and until the late 1850s would prove to be stiff competition to Colt single action revolvers. Allen produced more than 10,000 pepperboxes between October 1846 and March 1848, more than all Colt hand and shoulder arms manufactured between 1836 and 1848.The Allen offered a number of advantages over the Colt revolver, but the Allen had one glaring disadvantage which sometimes brought ridicule.

It wasn’t long before the pepperbox’s advantages became apparent to potential customers. First, the double action (“self cocking”) feature made the pepperbox a little faster firing than a single action Colt. The former was less expensive with a basic retail price of around $9 to $11 depending on the size and with its smooth bar hammer there was little to snag on clothing when drawn quickly from a pocket. Since there was no gap between cylinder and barrel, precise alignment to avoid shaving lead was not a concern and there was no buildup of powder residue at that junction as in a Colt. Another potential problem of multiple discharge, more than one bullet firing at the same time, was not a concern as it sometimes was with a Colt, only that the pepperbox then performed as a volley gun instead of discharging one shot at a time!

The demand for Allen pepperboxes increased substantially as the rush to the California gold fields began after the discovery of the precious metal there in 1848. Letters, diaries, and other writings from California mentioned Allens as often as Colts. J. F. Bekeart, first of three generations of gunsmiths, in early 1849 arrived by ship in San Francisco. He set up shop in Coloma in a shanty with a canvas roof with 100 Colts and an equal number of Allens on consignment from New York dealer A. W. Spies. Nineteen-year old George Dornin arrived penniless in San Francisco but with an arsenal of a double barrel rifle-shotgun and an Allen pepperbox. He soon discarded the Allen “as being more dangerous to the shooter than to the shot-at.”

No pepperboxes were adopted for military use although Allens were purchased privately by some military personnel and carried during the second Seminole war in Florida and the Mexican-American and Civil War. In 1856 the U.S. Navy did obtain and tested favorably five pepperbox handguns made by Eben Starr who later supplied the Federal army with carbines and revolvers during the War Between the States. No purchase of Starr pepperboxes by the Navy followed and no specimens are known to exist today. General George Crook in the 1880s recalled a fight with Indians on the Pacific coast in 1857. “I saw a soldier shooting at an Indian with one of those old fashioned ‘Allen pepperboxes’ having discharged his rifle, and keeping his mule between himself and the Indian.” Crook used his rifle to end the duel.

Allen’s patent didn’t expire until 1851 but earlier there were competitors offering multi-barrel pepperboxes. About 1840 Blunt & Syms was producing pepperboxes with a ring trigger and a concealed underhammer. Others by Robbins & Lawrence also used a ring trigger but had a fixed cluster of barrels and a concealed rotating striker. Capable of improved accuracy was the single action pepperbox by Stocking & Company with a long cocking spur on the hammer. Late in 1849 dealer S. C. Jett of St. Louis was selling Allen, Colt, and “Blunt and Syms revolvers” and Child, Farr & Co. of that city advertised they had just received a consignment of “Stocking & Co.’s new patent revolving pistols.” Well made as these competing arms were, none matched the Allen in sales. After 1851, such firms as Manhattan Firearms Manufacturing Co. and William Marston offered double action pepperboxes which were virtually identical to those by Allen. Marston marketed some under such trade names as Washington Arms, Union Arms, and Phenix Armory. Pepperbox revolvers also were produced in substantial numbers in Great Britain and on the European continent, ranging from plain to elaborate, and including one ungainly monstrous Belgian example with 24 barrels! Any more than eight barrels was uncommon.

By the early 1860s, with the influx of various revolvers by Colt and others here and abroad, the popularity of the percussion pepperbox was waning. However a form of pepperbox persisted in the early metallic cartridge era in the form of four and five barrel pistols by C. Sharps, Remington, and Starr in which the barrel cluster was stationary and the firing pin rotated. In true pepperbox form was James Reid’s “My Friend” knuckle duster metallic cartridge revolvers with seven barrels in .22 caliber or five barrels in .32 or .41 caliber.

Charles Worman is the author of Gunsmoke and Saddle Leather: Firearms in the Nineteenth Century American West and Firearms in American History: A Guide For Writers, Curators, and General Readers. He has also co-authored the two volume series Firearms of the American West 1803-1894. He has appeared in episodes of the TV series The Real West and Tales of the Gun. Charles is retired from the position of curator/deputy director of the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force and currently a Fellow of the Company of Military Historians.

-

- Assign a menu in Theme Options > Menus WooCommerce not Found

Related posts: