By Thomas Denenberg, PhD

John Wilmerding Director and CEO, Shelburne Museum

The exhibition All Aboard: The Railroad in American Art, 1840-1955 is on view at the Shelburne Museum in Shelburne, VT from June 22-October 20, 2024.

Few inventions have engendered such a complete reorganization of American culture as the railroad. Perhaps only the internet vies for the top prize and, even at that, the digital revolution is literally ethereal when compared to the wholesale changes wrought by the railroad to the social fabric of North America.

The “Iron Horse,” rued as a demonic presence in the landscape when first introduced in the United States, quickly created unprecedented economic prosperity in this young nation while at the same time displacing Indigenous cultures, provoking labor unrest, and serving as the prime mover for the country evolving into a modern nation. Trains also captured the attention of visual artists. Time and time again, railroads—and later the subway—provided the setting for painters exploring the drama of a changing America, a heterogeneous people and place coalescing into something new in the decades that bracketed the turn of the century.

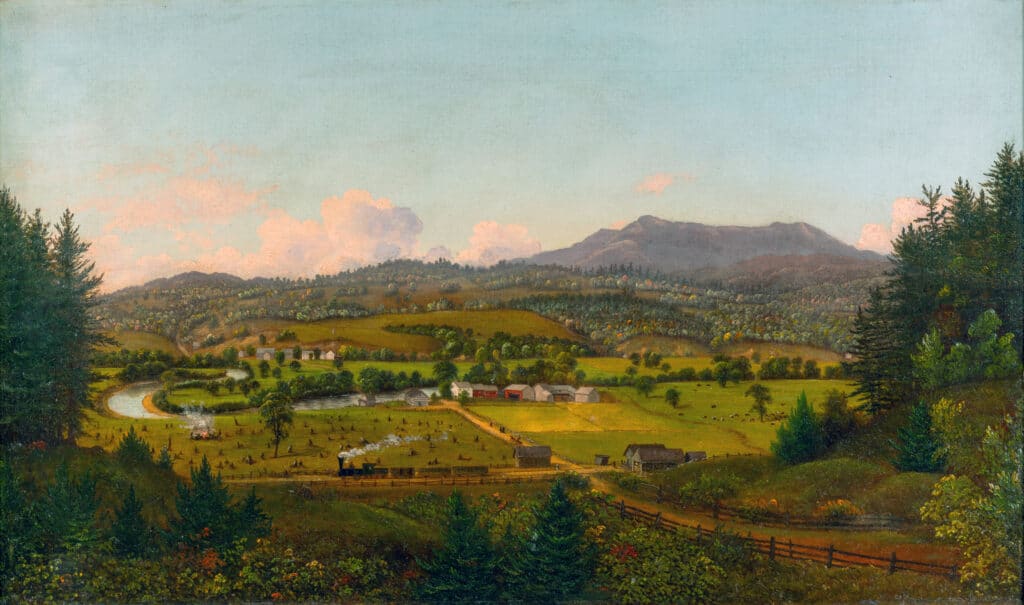

Vermont’s own Charles Heyde (1822-1892) is an archetype, one of many 19th century painters who sought to make sense of the conflict between the promise of the railroad and the potential for change, even loss. This first vexed moment in American visual culture, aptly named “The Machine in the Garden,” by literary critic Leo Marx, is on full display in Heyde’s Steam Train in North Williston, Vermont, ca. 1856, (title image, above) where a small train augurs change, symbolized by the adjacent field of cleared trees.Within years of the arrival of the Vermont Central Railroad in 1850, North Williston would boast grist mills, a poultry warehouse, a cheese factory, creameries, and New England’s first cold storage plant, enabling the exportation of meat and other perishables to other parts of the Northeast. Countless other artists such as Asher Durand (1796-1886), John Frederick Kensett (1816-1872), and George Inness (1825-1894) would chronicle the development of the railroad in New England and as it headed west – often depicting the scene as a promised land.

29 ¼ x 21 ⅞ in. de Young Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco; Gift of Anna Bennett and Jessie Jonas in memory of August F. Jonas, Jr.

The German-born Albert Bierstadt (1830-1892) stands out for his ability to limn the American West as a Garden of Eden. His View of Donnor Lake, California from 1871-72 not only documents the spot made famous for the doomed Donnor party—already the stuff of legend by the time Bierstadt sketched the scene—but, more importantly, it depicts the pass through which the Central Pacific Railroad traversed, opening the region for development. Bierstadt’s paintings were highly regarded in his lifetime, serving as advertisements for the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, or the perceived right of the United States to move from coast to coast in the 19th century. This belief can be read at every turn in the visual culture of the era – witness Westward the Star of Empire from 1867, painted by Theodore Kaufmann (1814-1896). Kauffman—German-born like Bierstadt—painted the grand narrative fiction of the West, that of Indigenous insurgency. A group of Native Americans has furtively approached the train tracks crossing the prairie from the cover of tall grass and surreptitiously removed two sections of rail. The impending cataclysm in the painting stoked period anxieties, but also made clear that such resistance would prove futile in the end. The demographic conquest of the West may have been in question in the late 1860s, but not for very long, and it comes as no surprise that the historian Frederick Jackson Turner declared the frontier “closed” in 1893.

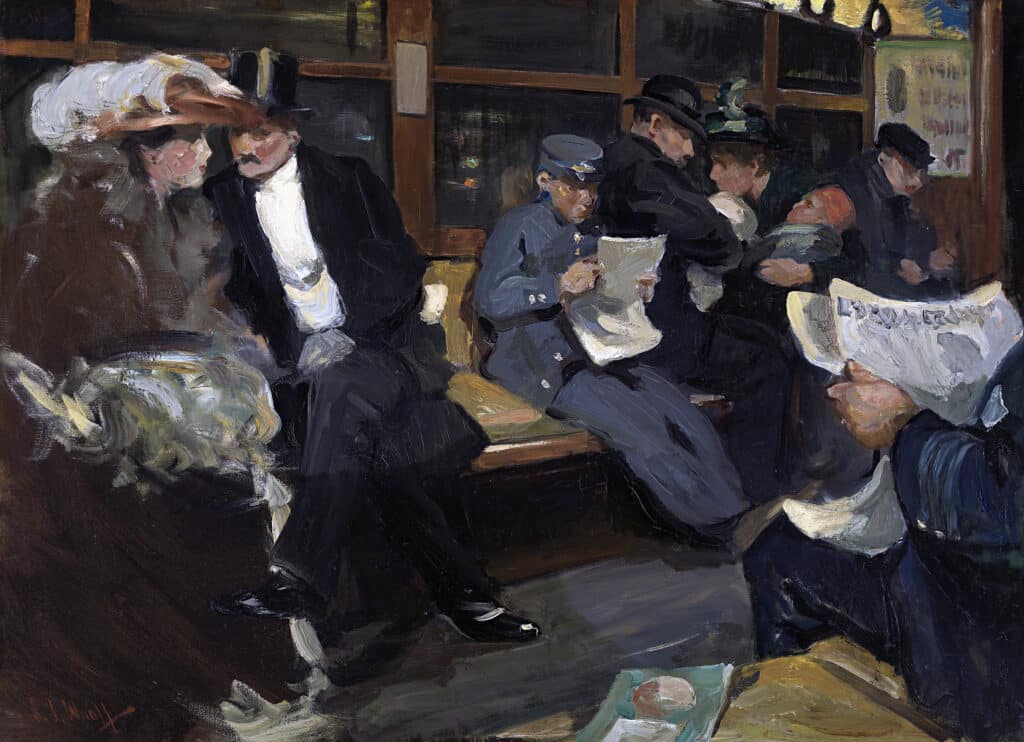

As the United States moved off the farm and into the city in the decades that bracketed the turn of the century, the scene shifted for artists fascinated by the subway. Subterranean mass transportation entered the popular imagination in 1863 with the advent of the London Underground, followed by advancements around the globe, including in New York City. Samuel J. Woolf (1880-1948) captured the excitement of riding the city’s new

Oil on canvas, 22 ½ x 30 ½ in. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Purchase, Funds provided by a

private Richmond foundation. ©Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Photo: Travis Fullerton.

subway system in his 1909–10 painting The Under World. Opened in 1904, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company, or IRT, offered an alternative to earlier elevated rail systems and accommodation for all strata of New York society, from the immigrant family at right to the uniformed messenger boy reading the newspaper in the center. Within twenty years, the IRT connected Manhattan to the outer boroughs as never before. The painting’s theatrical focus, however, is at stage right, where a man in an evening dress leans over to whisper confidences to a woman dressed as a fashion plate – complete with a fur collar and plumed hat. Employing a brushy realism, Woolf conjures a place where class, ethnicity, and gender roles slip earlier social expectations, and gentility is redefined in the new public space of the passenger car.

Boston, the fifth-largest city in the United States at the turn of the 20th century, is quite unlike Woolf’s New York and is invariably framed in terms of filial piety to its Puritan origins. New England authors such as Hawthorne and the “schoolhouse poets”—Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and John Greenleaf Whittier—set the stage in the 19th century with works that helped define New England as a region of rectitude and quiescence. Painters like Edmund Tarbell (1862-1934), immersed in this literary culture, reinforced historical sensibility at every turn. Influenced as much by 17th century Dutch interiors as by the radical themes and techniques of French Impressionism, Tarbell and his followers developed a signature style that coalesced into the Boston school. Dubbed “Tarbellites” in 1897 by the critic Sadakichi Hartmann, the Boston school promulgated a vision of an idealized “old” New England that placed a premium on a timeless genealogical imagination. Tarbell, of old Yankee descent himself, leveraged his lineage to become an arbiter of taste, defining a look for Boston’s Brahmin class, whether on Beacon Hill or an island in Maine during the summer.

Tarbell, Edmund Charles, American, 1862-1938

Oil on canvas, 24 3/8 in. x 32 in. (61.91 cm x 81.28 cm), Crocker Art Museum, gift of Dr. Joseph R. Fazzano 1956.7

In the Station Waiting Room, Boston of 1915 is an unusual departure for Tarbell as it is set in a public space, rather than a genteel domestic interior. Light fascinated the painter, and his manipulation of sun and shade provoked critical reactions throughout his career. “The effect of sunlight falling on figures … has seldom been represented with greater force and accuracy,” declared a satisfied reviewer in The Boston Evening Transcript in 1890. Shafts of heavenly illumination pick out a family in the middle distance, calling our attention to a mother and child waiting patiently while a couple of swells sporting boater hats jog by, late for their train. Tarbell’s waiting room places modernity in contest with tradition. In foregrounding three female sitters in white summer dresses, Tarbell assures the viewer that technology marches forward and cities grow, but traditional female virtues are a constant in Boston. Tarbell would live until 1938, old enough to see such assumptions challenged and updated.

As the economic and political center of the United States migrated from New England to an idealized “middle America” in the 20th century, visual culture kept pace. Painters such as Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975), an artist trained in New York and Paris, eschewed earlier sentimental traditions or the new European movement toward abstraction in favor of a sinuous, exaggerated realism that rendered the American scene as if in a dream state. Trains captivated Benton. “My first pictures were of railroad trains,” he wrote later in life, continuing, “Engines were the most impressive things to come into my childhood. To go down to the depot and see them come in, belching black smoke with their big headlights shining and their bells ringing and pistons clanking, gave me a feeling of stupendous drama, which I have not lost to this day.”

Oil on panel, 29 7/8 x 41 3/4 in. Memphis Brooks Museum of Art; Eugenia Buxton Whitnel Funds, 75.1. © T.H. and R.P. Benton Trusts / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS),

New York.

Benton’s Engineer’s Dream of 1931, despite the cheerful, illustrative palette and comic pose of the railway worker at right, is in fact the stuff of a nightmare. An engineer, asleep in his bed, conjures a steam locomotive, canted as if caught by camera or projected on a movie screen, speeding to the precipice of a washed-out bridge while a forlorn figure is caught in the blinding sweep of the headlamp, frantically waving a red signal flag. The diminutive engineer—presumably the sleeping protagonist—has leaped from the controls to an uncertain fate. The painting is fittingly symbolic of economic conditions in the United States two years into the Great Depression.

The valorization of labor organized the creative culture of the Depression, especially among writers and artists who took workers as subjects. Harry Gottlieb (1895-1992) painted Dixie Cups in 1936–37 as one such painting, a stark representation of the monumental glowing red railcars used in the production of steel, steaming in the cold air, and painted in the darkest days of economic crisis. Belying their innocent-sounding sobriquet, these specialized railcars shared little in common with the ephemeral paper drinking cups that sprang up in public washrooms as part of a public health effort aimed at curbing the 1918 influenza epidemic. Indeed, these vessels contained slag, a byproduct of the steel industry, and transported the red-hot waste from blast furnaces in cities such as Cleveland, Detroit, and Bethlehem to immense dumps that resembled an infernal region.

In the years that followed the efforts of Benton and Gottlieb, American culture conspired to engender a cool nostalgia when it came to depictions of the railroad. Imagery of people hard at work on the rail gave way to frank depictions of cities and infrastructure, a shift suggesting that the transformation of American culture wrought by the train had reached a point of completion. From World War II onwards, changes to the cultural topography of America would be left to another machine – the automobile.All Aboard: The Railroad in American Art, 1840-1955 is open from June 22 to October 20, 2024, and features 40 masterworks of American painting, borrowed from museums across the country to explore the relationship between technology and creative culture. Organized by Dixon Gallery and Gardens, in Memphis, TN, The Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, NE, and Shelburne Museum, the project is yet another example of the many ways we leverage our renowned collections to bring world-class exhibitions to audiences here in VT. The exhibition is accompanied by a diverse schedule of programs and amplified by an elegant scholarly catalog available in the Museum Store. All Aboard: The Railroad in American Art, 1840-1955, will be on view in the Murphy Gallery, Pizzagalli Center for Art and Education, June 22 through October 20.

Related posts: