By Douglas R. Kelly

A vacation or a business trip, for me, just isn’t complete without at least one visit to a flea market, antiques mall, or junk shop. A little time spent researching an area before traveling can pay off with a great score in a far-away place. Before the Internet, of course, it was a whole lot harder to do this; generally speaking, “the hunt” was much more of a hit-and-miss affair.

A 1986 family vacation to Long Beach Island, on the Jersey Shore, fell into the “hit” column. The house we rented in Haven Beach turned out to be a stone’s throw from two antique shops, one of which had a decent group of vintage toys for sale. The shop had once been a Cape-style home, so the merchandise was crowded into every room, nook, and cranny of the place. Looking over a group of toy cars on the top shelf of a bookcase in a back room, I spotted what I thought was a recent die-cast model of a Plymouth Valiant. I realized as I picked it up and turned it over that it was too light to be a die-cast, and the friction motor clinched it. A tinplate Plymouth, made by Bandai in Japan in the 1960s, and in decent condition. No box, but I didn’t care as I coughed up $8 for the thing and took it back to our rental house for a gentle cleaning.

I’d read a bit about tin toy cars but this was the first I had been able to buy. Bandai’s Valiant wasn’t the most accurate toy car, nor was it in any way rare (you can easily find a number of examples for sale online). But the combination of the tinplate shape, that friction motor and those rubber tires was magical, and I was hooked.

Toy Versus Model

Japanese toy makers, like their American and European competitors, made toy cars before World War II. The majority of Japanese-made toy cars of the 1930s were crude, fairly basic models, but there were some exceptions. One was the blue wind-up car shown here, possibly made by CK, based on the 1935 Chrysler Airflow. The hood is a little too tall and the hood ornament a little too large, but the maker captured the aerodynamic lines of the Airflow quite well for the time.

World War II, of course, put a stop to toy production in Japan, not unlike here in the U.S. When Japanese manufacturers began making toys again starting around 1947, they did so due in large part to the work of the U.S. military, which helped rebuild factories and infrastructure in Japan. The early post-war toys were often stamped with the words “Made in Occupied Japan,” and the tinplate cars generally were somewhat crudely designed and manufactured (although some of them had a real charm).

As Japanese manufacturers gradually improved the quality of their products, Marusan introduced a 12-inch tinplate Cadillac in 1952 that changed the game. The friction-powered car boasted something like 150 individual parts, which helped make it an authentic replica of the full-size Cadillac. For the first time since the 1930s, a Japanese tin toy car could lay claim to being an accurate model, and Marusan sold as many as it could turn out.

About 30 years ago, I interviewed a couple of prominent collectors of Japanese tin cars, one of whom was Ron Smith. Based in Solon, Ohio, Smith was a knowledgeable authority on these toys, and he shared with me his memories of Marusan’s game-changer. “I remember being at a show in Ohio in the early 1970s, and a fellow by the name of Jack Lord had just [bought out] a little store up in Chicago. He brought in these large, grotesque Marusan Cadillacs and was selling them for $15 apiece at this show. He had a dozen of them and I think he sold four of them at the show. Then when I caught up with him at the Dearborn show the following week, I realized I made a mistake by not buying more. They now were up to $25, so like a dummy, I bought [only] one more.” Oh, to have been in Dearborn 50 years ago: near-mint examples of the Marusan Cadillac, with the original box, today regularly go for $1,000 to $2,000 depending on the color.

It was during the 1970s that collector attitudes started changing in the toy car world. Cast iron toys were king, along with large pressed steel toys, and tin toys didn’t get much respect. “People just kind of shunned the Japanese tin altogether,” Smith told me. “I don’t know whether there was still some resentment from World War II as to why people didn’t want to buy this, or [possibly] they thought of it as cheap.” Some of what the Japanese makers made was indeed cheap, with more than a few tinplate cars being misshapen and inaccurate. But many manufacturers began to hit their stride during the 1950s, turning out tinplate toy cars that were exported in large numbers to the U.S. Many were highly accurate models of Buicks, Dodges, and Studebakers. It was this combination—a toy car that also was an authentic replica of the cars that were seen on the streets every day—that collectors began to recognize as being highly desirable.

Driving the Market

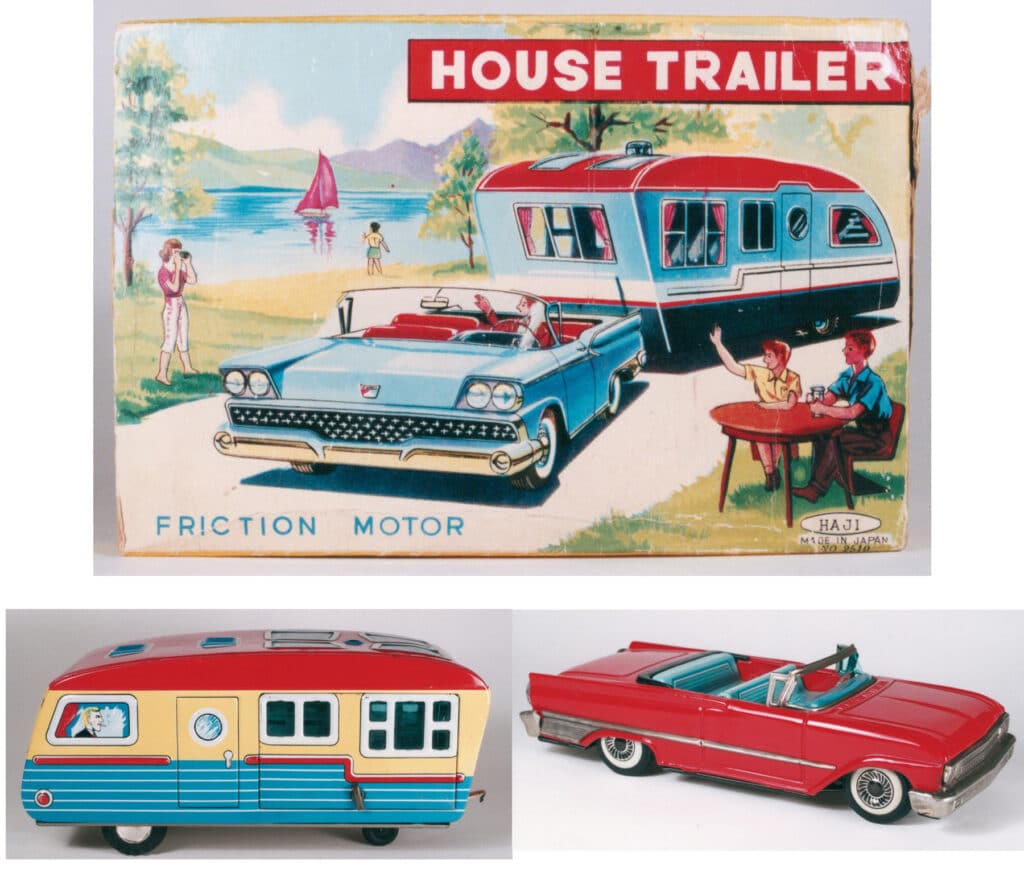

That desirability translates to healthy prices for the good stuff. Original (meaning unrestored) 1950s and early 1960s Japanese tinplate models of American cars, when they’re in excellent or better condition, generally start in the $150 to $250 range and can run into the thousands for the rarer examples, especially if the original box is present. Interestingly, most collectors prefer cars powered by friction motors (or by clockwork motors) rather than those that came with remote control features or that had what’s often called “mystery action,” which causes a toy car to move in a haphazard or unpredictable way.

Size makes a difference when it comes to Japanese tin. Larger toys generally come with higher asking prices; unless it’s a particularly rare toy, a 12-inch Chevrolet will fetch more than an 8-inch example (in the same condition, of course).

In addition, the size of the toy affects accuracy. The process of bending and shaping sheets of tinplated steel is less precise than the process of pouring molten metal into molds to make die cast models. This means that smaller shapes and curves are more difficult to replicate; so the larger the roof or door or fender, the more smoothly the tinplate sheet will conform to the proper shape.

By the mid-1960s, the “golden age” of Japanese tin toys was coming to a close. Manufacturers were transitioning to making plastic toys, and even those still making tinplate toy cars began adding features like light-up parts and mystery action mechanisms. Collectors today have little interest in these more fanciful toys.

Not surprisingly, condition is an important consideration for most collectors. Original condition (meaning near mint to mint) toys are the most in-demand and sell for the most dollars. That includes the friction motors that so many of these toys feature; fully functioning motors are very desirable due to the difficulty of opening up the toy to effect repairs. The good news is that it’s more difficult to restore and repair tinplate toys than it is die cast toys/models; it seems like the surface of a tinplate car doesn’t accept paint as smoothly as the surface of a die cast piece, so there are far fewer restored tinplate toys out there than die cast toys. A good clue to restoration are the tabs that hold the body to the baseplate/chassis: if the tabs are damaged (dinged up and/or missing bits of paint), it’s likely they’ve been pried up at some point to allow separation of the body and chassis for re-painting or repair. Be aware also that repro/replacement parts have been made for some Japanese tin toys. These can be hard to spot, so it’s best to handle and examine as many original toys as you can in order to develop an eye for originality.

Copies and Repros

Over the years, several reproductions of Japanese tinplate cars have been introduced. The best of these was the “Fifties” line that came out in the mid and late 1980s. Based in Tokyo, Fifties produced four tinplate models that were roughly 1:18 scale: a 1950 Buick (coupe and convertible versions); a 1950 Cadillac (coupe and convertible); a 1953 Chevrolet Corvette (coupe and convertible); and a 1956 Ford Thunderbird (you guessed it, coupe and convertible). Each came in various colors (with friction motors, naturally), and the boxes featured period 1950s-style artwork. Each model also came with a 6-inch by 3-inch “certificate of title” card and registration form. The models weren’t hyper-accurate replicas, but they have a toy-like charm that makes up for that, and they were well-made products. Complete examples with box, card, and form generally sell for $25 to $50, depending on model and color, which is about what they sold for back in the 1980s. It was thought that the company planned a fifth model, which Ron Smith told me was to be a 1957 Chevrolet, but it apparently never was produced.

It didn’t take long for Chinese knock-offs of the Fifties cars to appear. They’re easy to spot as the quality of the fit and finish is inferior, and the baseplates have no identifying marks. If there’s any doubt, the makers made it easy by including “Made in China” on the rear license plate holders.

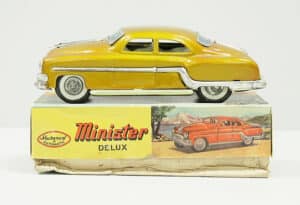

The “Minister Delux” knock-off is a little trickier. These were made by Amar Toy Co., near Delhi in India, during the 1980s, and were made to look like a Pontiac tinplate car made by Asahi (ATC) during the mid-1950s. The 10-inch-long Minister is a poorly designed and poorly made copy of the Asahi, but the style and the box artwork often fool people into thinking it’s a legitimate 1950s item. The brightwork (headlights, bumpers, side trim) often corrodes, further adding to the false impression, and the “Made in India” and “Amar Toy” logos on the box often are blacked out or covered with a sticker. The $50 to $75 that sellers often ask for these is way too much (actually, $20 would be too much). In my view, you’d do better to put the money toward an actual 1950s Japanese tin toy.

Learn More

There are lots of websites offering information on Japanese tin toy cars, but several excellent books also have been published that each contain a wealth of information on the subject. Teru Kitahara has published numerous books on the subject, but for my money his first three books—the Tin Toy Dreams series—reign supreme. Look for the one titled Cars, a paperback published in 1985. Dale Kelley’s book, Collecting the Tin Toy Car, a hardcover published in 1984, will help fill in a lot of blanks, both with Japanese tinplate and European manufacturers. Ron Smith published two books on the subject in 2003 and 2004, each called The Big Book of Tin Toy Cars. Look for the one focusing on passenger and sports cars. And Andrew Ralston’s Tinplate Toy Cars was published in 2008. All recommended reads.

Douglas R. Kelly is the editor of Marine Technology magazine. His byline has appeared in Antiques Roadshow Insider, Back Issue, RetroFan, Diecast Collector, and Buildings magazines.

Related posts: